This digital history project utilizes methodologies of text data analysis and distant reading to assess how local newspapers produced their own discursive representations of the U.S. and the world in response to the ideologies of American colonialism and exceptionalism embedded on the grounds of the St Louis 1904 World's Fair. 1 (Anderson 2006; Douglas 1989: xviii) The project understands the Louisiana Purchase Exposition as a complex microcosm of early-twentieth-century modernity embedded with ritualistic competition, contradictions, and tense power relations between geopolitical entities. It pushes for closer scholarly attention to how newspapers, as intermediaries of fair makers’ ideological messages and visitors’ spatial experiences, engaged with and interpreted the language of empire and American colonialism at the fair.

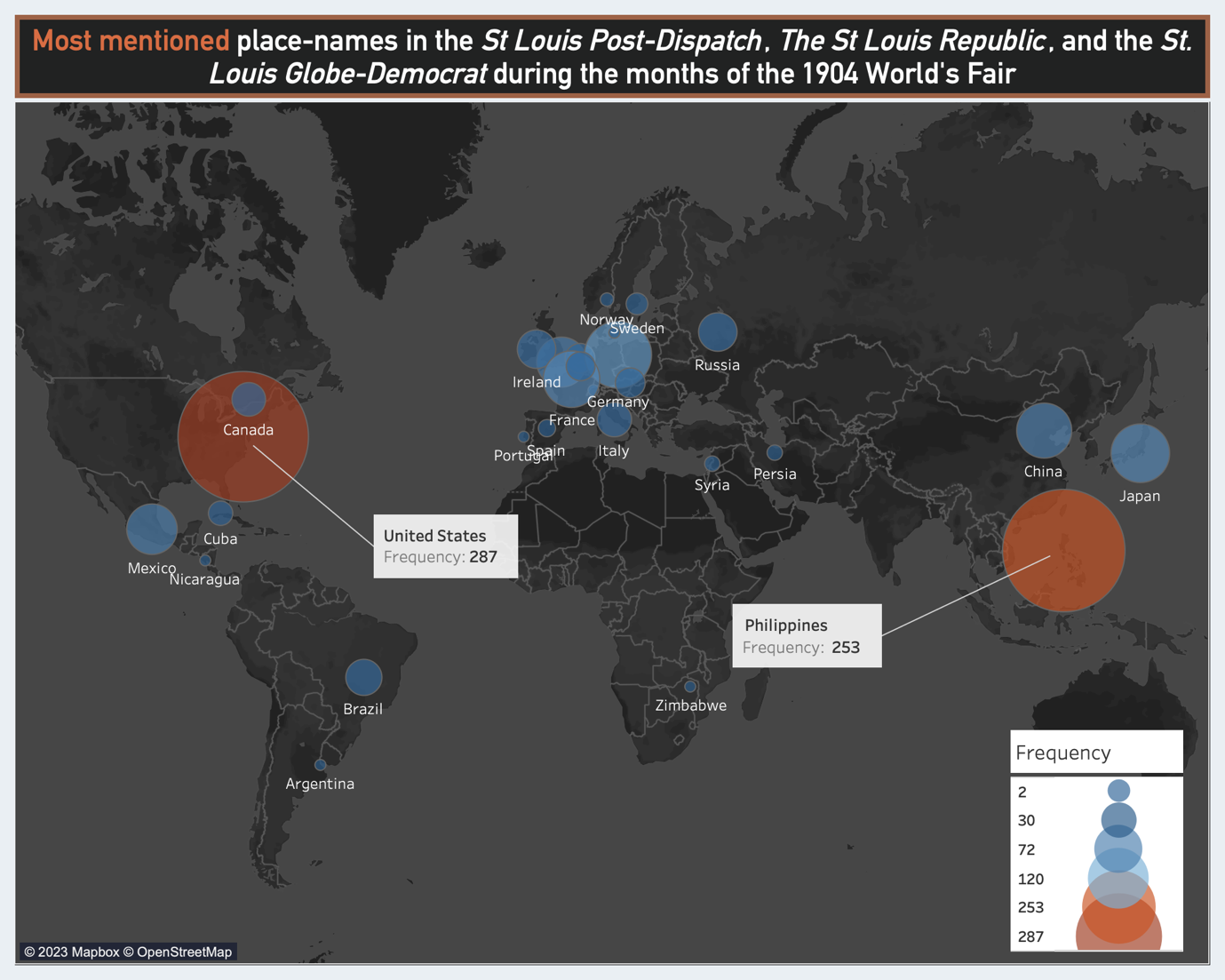

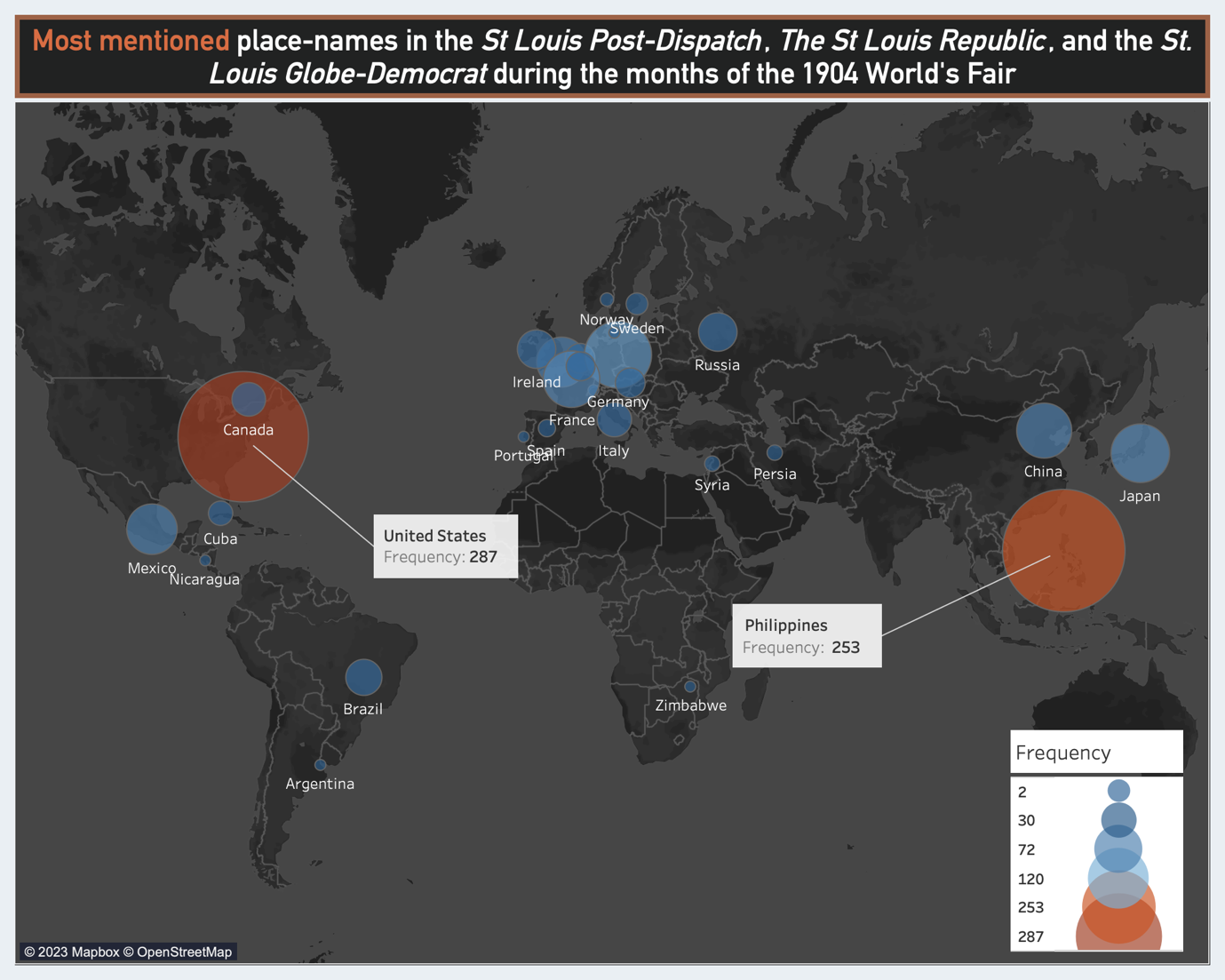

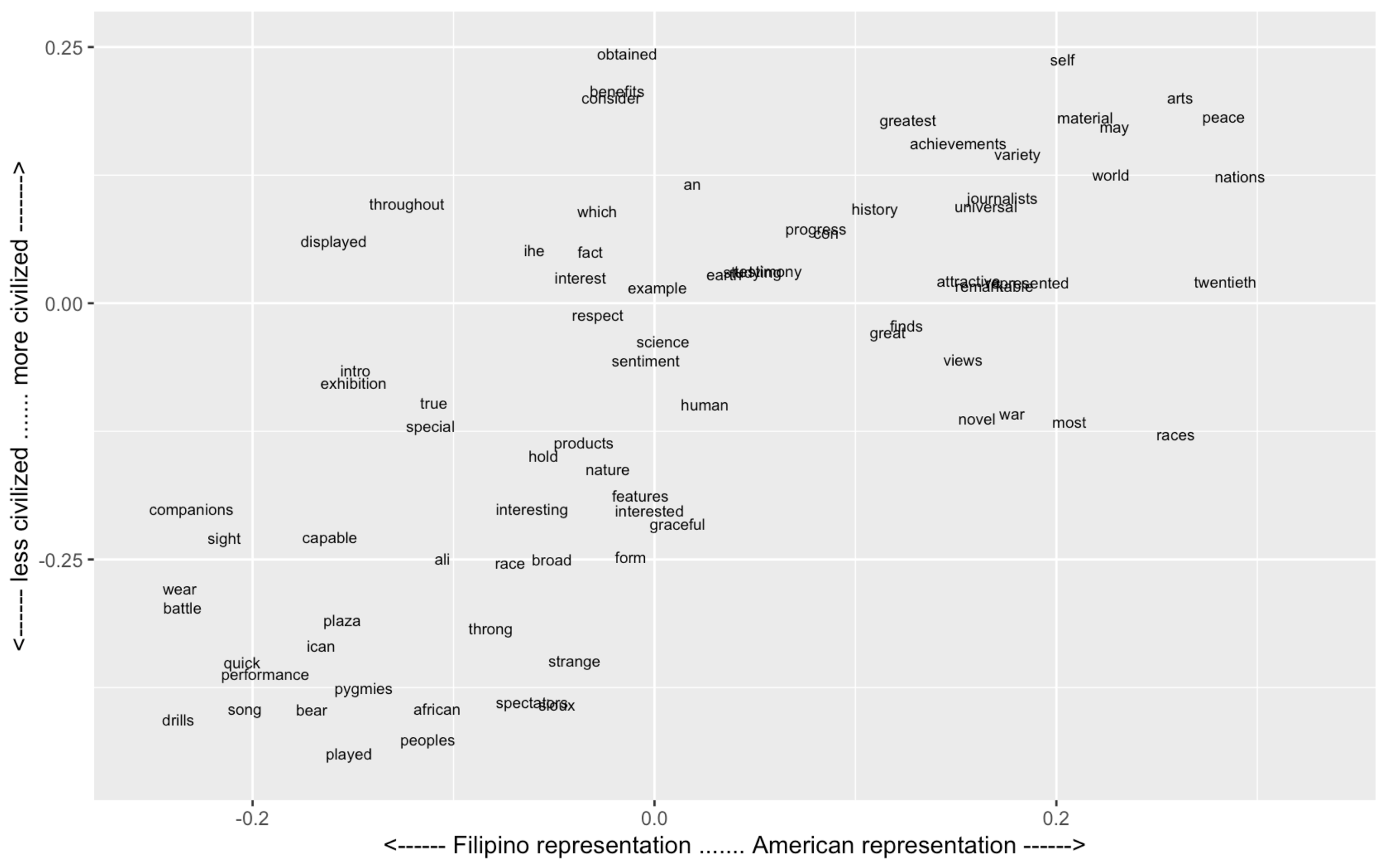

Newspapers relied on the ways in which multiple audiences perceived and experienced the fair exhibits in order to write their stories and produce complex representations of participating cultures and the modernizing world. By attending to the cultural commentary about the fair through the use of digital methodologies, the project argues that, in response to the power relations and discursive negotiations embedded on the fairgrounds, newspapers contributed to an "imagined geography" of the modernizing world centered around the United States as an emerging, exceptional colonial power at the turn of the century. 2 (Anderson 2006; Blevins 2014: 122-147; Lefebvre 1991; Said 1979) They did so, first, by printing placenames of the United States and the Philippines more often than every other geopolitical entity participating at the fair (see Figure 1). Second, by fostering conversations about the Philippine exhibit as a center piece of the exposition and characterizing Filipino people as a nation under American tutelage and guidance towards civilization.

The data in this project derived from newspaper clippings retrieved from the digital database Newspapers.com. The clippings were stored in JPG files that were then OCR'ed and processed as plain text data in RStudio. The collection was done through both random and proportional sampling, which means that the textual data is proportionally distributed across the three newspapers selected for collection ( The St Louis Republic, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and St. Louis Globe-Democrat ). The data is also proportionally distributed across the seven months of the fair using a fix interval of 15 days. With a raw count of 196,336 words, the corpus serves as a significant sample of a larger process of data collection with potentially similar patterns to be explored for further research. Employing named entity recognition (NER) to extract the most frequent placenames in the corpus and using word embedding models (WEM) to explore the semantic relationships between words like “savage” and “civilization” reveals how conversations about the world’s fair in local newspapers contributed to the symbolic legitimation of the American occupation and colonial control over the Philippines.

Some methodological choices and interventions on multiple levels of the research process – the data, the code, and the analysis – were necessary to mitigate issues of OCR errors, algorithmic bias, and limitations of the data. In the words of Shanon Leon, when it comes to humanistic inquiry, most data sets cannot “stand on their own without clear and thorough documentation that accounts for the many decision points along the way.” (Leon 2019: 10-11) Further, Stéfan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell have argued in favor of the interpretive responsibility of humanists and historians engaging with text analysis and quantitative methodologies. They remind us that computational tools do not produce meaning; they are rather meant to “facilitate the augmented hermeneutic cycle.” (Sinclair / Rockwell 2016: 345). In this sense, without human intervention based on thorough knowledge of the input data and its historical context, the automated process of extracting named entities, for instance, would have risked misrepresenting particular geopolitical entities that participated at the fair. Beyond simply presenting the preliminary findings of this project, I hope to raise some of the methodological concerns regarding text mining for historical analysis that informed the scope of my research questions and the core argument of this project. I am currently collecting more data to expand the analysis and include other world’s fairs at the turn of the century.

Here, the understanding of newspapers as mediators that both influence and are informed by competing values, attitudes, and ideology in the discursive dimension relies on the work of Susan J. Douglas. The mediation resulted in new discursive representations of the United States and the world, and as per Benedict Anderson’s framework, contributed to shaping “imagined communities” and their modern geography.

This project relies on Cameron Blevins’ terminology and framework to understand how newspapers “print, and thereby privilege, certain places over others.” Blevins relied on Henri Lefebvre’s notion of space as a social construct and Edward Said’s idea of imaginative geographies.” He also took into consideration Benedict Anderson’s work on imagined communities.