1.

Introduction

The use of digital methods to study classical texts has increased in recent years,

1

as exemplified by initiatives such as the forum

The Digital Classicist, which has promoted exchange in the associated field of research since 2005.

2

Nevertheless, corpus-based digital research on Roman drama specifically has not been a focus so far.

3

Statistical research on Roman drama, on the other hand, has been carried out for decades. For example, Gilleland (1980) computed statistical data to analyse differences between character types as well as between male and female characters in Roman comedy with a focus on specific parts of speech, such as interjections. Barrios-Lech (2016) researched linguistic profiles of characters in Roman comedy. Other scholars analysed differences between female and male speech in Roman comedy by using statistical methods, such as Dutsch (2008).

4

However, digital methods seemingly have not been applied to Roman drama on a larger scale yet.

2.

Technical Information

This is where RomDraCor comes into play (Beine / Fischer 2023). It is embedded in the DraCor infrastructure (Fischer et al. 2023; Börner / Trilcke 2023; Fischer et al. 2019), which at the time of writing features 25 corpora of plays in 19 languages, ranging from antiquity to the 20th century. RomDraCor includes 20 comedies by Plautus, 6 comedies by Terence, and 10 tragedies by Seneca. Full texts were taken from Perseus Digital Library (Crane et al.), then updated to TEI P5, corrected, and enriched with additional markup.

5

The TEI files are based on digitised editions in the public domain (Plautus 1895–1896; Seneca 1921; Terence 1857). Although some date back to the 19th century, these texts are suitable for digital analysis and distant reading. A comparison to more current modern editions is particularly useful if the division of acts and scenes is significant for a specific approach. The same applies to speaker attributions which sometimes differ between editions.

For instance, Leo’s edition of Plautus’

Aulularia, which the TEI file in DraCor is based upon, labels the slave speaking in verses 280 to 370 Pythodicus. By contrast, Lindsay’s edition denotes the same slave in verses 280 to 362 as Strobilus and in verses 363 to 370 as Pythodicus. Furthermore, Leo designates the slave speaking in verses 586 to 681, 701 to 712, and 808 to 833 as Strobilus. In comparison, Lindsay calls him

servus Lyconidis. Although we operate on a large scale with a corpus-based approach, such small differences can have a significant impact on extracted structures and values and their subsequent analysis. For example, a co-occurrence network graph may look different as the underlying data has changed. Researchers may address this question by downloading and adapting the files from RomDraCor according to their preferred speaker attribution. Other passages where the reading significantly alters this kind of network data are found in Plautus’

Mostellaria (Plaut.

Most. 515a, 517–518), or Plaut.

Pseud. 1330 (Leo) and Plaut.

Pseud. 1331b–1332a (Lindsay). For Leo’s edition, see Plautus (1895–1896). For Lindsay’s edition, see Plautus (1903–1905).

The DraCor platform not only offers the TEI-encoded text file but also readily available features. As mentioned above, it extracts and displays network data for each play. The data extracted from the plays can be downloaded in various formats such as GEXF and GraphML and further analysed with more sophisticated network analysis tools. In the following, we will present some of the enhancements and features of the texts in RomDraCor. We have especially enriched the information on characters. The identifiable 405 speakers have been given individual IDs and are marked up with their sex: male (278), female (104), plus mixed groups. Speakers are also classified by character types, such as the

parasitus (parasite), the

senex (the old man and

pater familias), the

servus (the slave), or the

virgo (the young girl).

This feature enables more differentiated analyses, e.g., with a focus on specific types of Roman drama. In this paper, we demonstrate this analytical potential. We will focus on the comedies by Plautus and Terence since they belong to the same genre, the

fabula palliata (“comedy in a Greek cloak”), which is based on Greek models. These comedies present stereotypes and are thus suitable for doing research on specific character types. The remaining Roman tragedies are

fabulae crepidatae (“tragedies in Greek tragic shoes”), which are based on Greek models, or, in the case of the

Octavia, attributed to Seneca, probably a

fabula praetexta (“tragedy in the Roman toga worn by magistrates”), which deals with Roman history. The Roman tragedies therefore seem more convenient for a comparative analysis with the Greek tragedies in the GreekDraCor (Beine et al. 2022).

3.

Use Case: Finding Typical Words through Stylometry

Regarding Roman comedy, RomDraCor facilitates stylometric analysis focusing on specific character types. Let us first quantify which types dominate speech in Roman comedy.

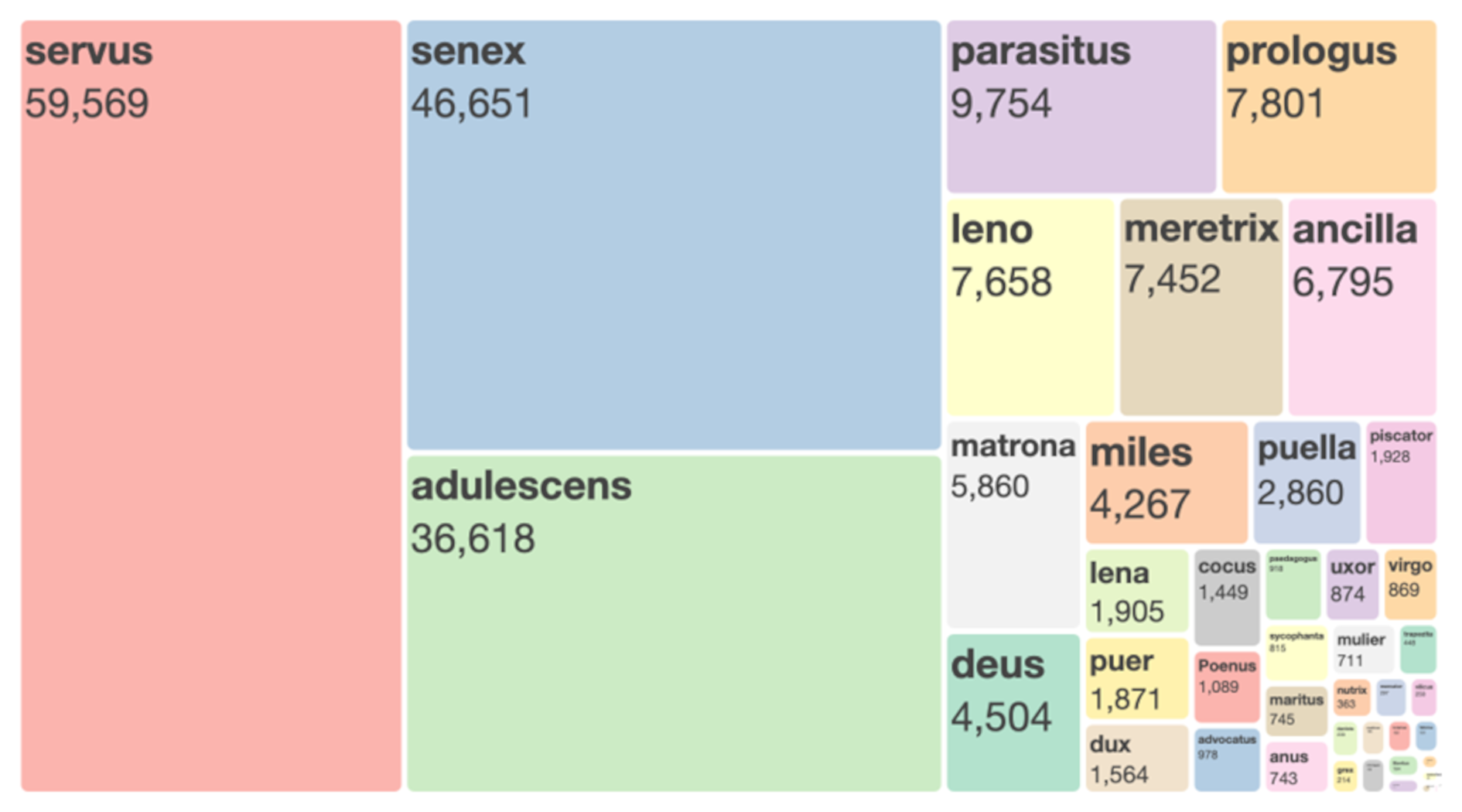

Figure 1. Treemap showing quantitative shares of all character types in the total word space of the comedies (counted in words). Licenced under

CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1 shows the verbal space allocated to the individual character types, totalled across all 26 comedies. As can be seen, the slave (

servus) ranks first, the old man (

senex) second, and the young man (

adulescens) third. This corresponds with the family setting and plot of Roman comedy. We can then determine which words are typical for a specific character type. For illustration, we will compare the speech of the type of the

senex with that of the

adulescens.

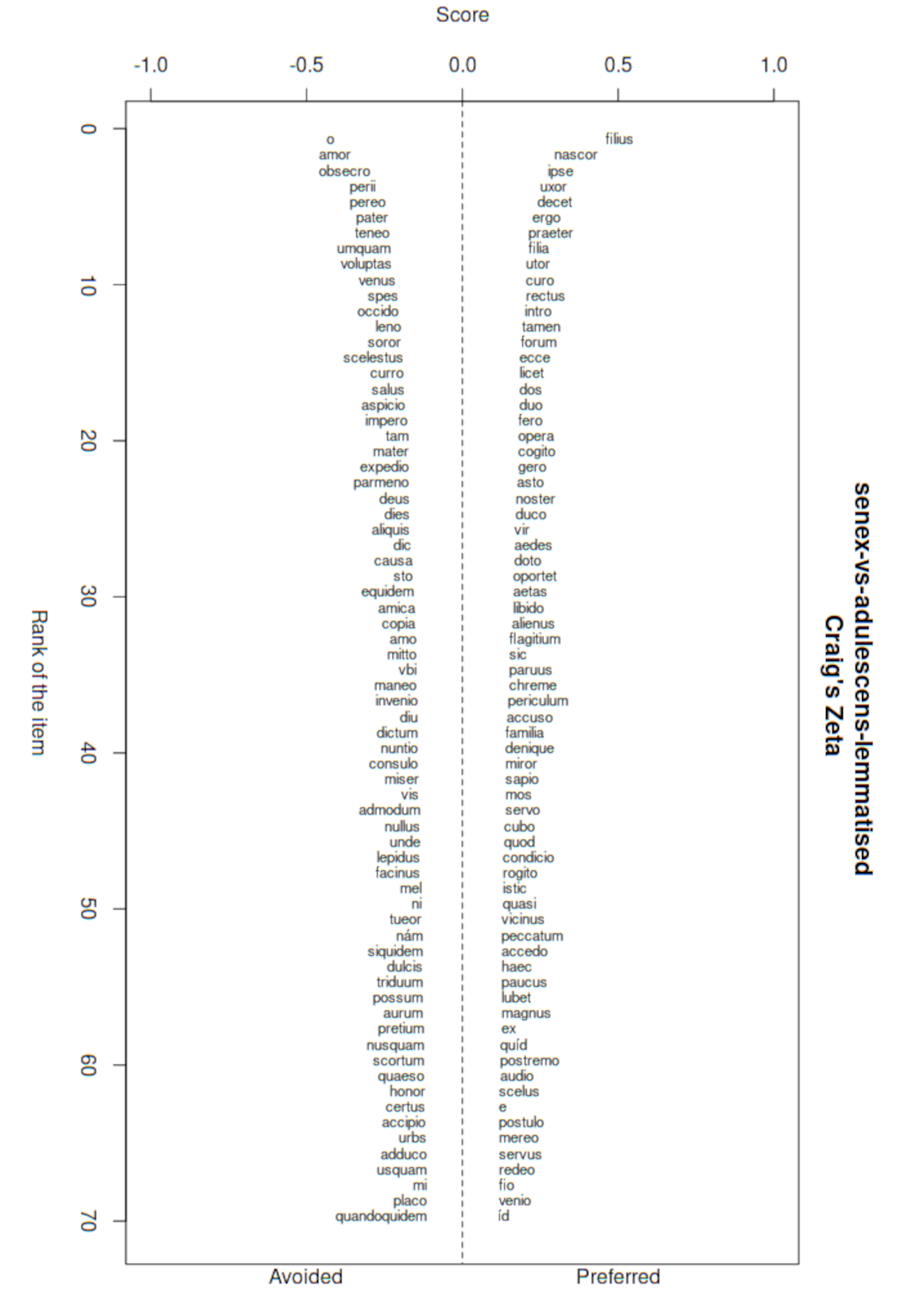

Figure 2 displays two lists of lemmatised words.

6

The list on the left shows the words which are favoured by the type of the

adulescens and avoided by the type of the

senex. The list on the right shows which words are favoured by the

senex and avoided by the

adulescens.

Figure 2. Two lists comparing the vocabulary used by

senes and

adulescentes in Roman comedy, highlighting the preferred and avoided words of the

senes. Licenced under

CC BY 4.0.

The words can be categorised in the following salient word fields. Both character types talk about

familia. The type of the

adulescens speaks about a father (

pater), who is actually a

senex, about a sister (

soror) and a mother (

mater); the

senex speaks about a son (

filius), who is actually an

adulescens, a wife (

uxor), a daughter (

filia), and the

familia. The speech of the

senex also shows the word field of generation conflict (e.g.,

filius, curo, dos, familia, servo, postulo) and the word field of values (e.g.,

decet, rectus, licet, oportet, flagitium, mos). The generation conflict seems also to be present in the speech of the

adulescens, but with an emphasis on settling the conflict (

placo). In comparison to the

senex, the

adulescens expresses emotions, such as love (e.g.,

amor, voluptas, venus), fear and despair (e.g.,

o, perii, occido, miser), and hope (e.g.,

spes, salus). This is due to the plot of Roman comedy. Usually, a young man is in love with a girl his father does not approve of. Sometimes, she is a slave and needs to be freed. Hence, the young man desperately seeks a solution and is often aided by a scheming slave. Because of this, we find the word field of pleas in the list of words preferred by the type of the

adulescens (e.g.,

obsecro, quaeso). Moreover, the

adulescens talks about ransoming his loved one (e.g.,

leno, scelestus, invenio, aurum, pretium). While the topics of Roman comedy are well known, we can now identify them in the speech of a specific character type and quantify them for each character type.

4.

Conclusion and Outlook

As shown, the features in RomDraCor facilitate more differentiated digital analyses of character types in Roman drama. They are not limited to stylometric approaches, the DraCor data also allow character types to be determined through network analysis (Beine 2024). Moreover, these features support interdisciplinary studies on character types of European drama through different languages and periods using the rich collection of corpora offered through the DraCor infrastructure.