Positing a single Enlightenment has always been contentious; this is even more the case in in the English-speaking world, where several different types of Enlightenment -- scientific, literary, philosophical -- appeared in different localities and in different social circles over a period of two hundred years. Due to this diversity of networks and cultural projects, we must consider the possibility that these English Enlightenments do not overlap meaningfully and examine closely the networks that do exist to see what connections the participants do have, rather than assuming a totality, or a single network, which may be chimerical. In order to locate these connections, I have decided to study the long tail of the English Enlightenment, looking at the correspondence, knowledge, and social networks of major figures of the Enlightenment like John Locke and Jeremy Bentham, alongside the English correspondents of major continental European Enlightenment figures like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, to see the extent to which these various Enlightenments overlap and interlock. The methods that I use here are essentially prosopographical, an accounting of correspondents of these major figures, but with network analysis as a secondary method.

Prosopography is the study of groups through their individual members and their connections, often through selective individual biographies or partial data. It has been an established method for studying groups of people who have been deemed notable by historians and others who create the historical record; it has a particular strength for studying marginal members of elites or groups that keep accurate records, such as members of churches or militaries. Despite its reliance on literacy and record keeping, prosopography is a method which can draw attention to marginal members of these groups like women, lower-class people, or domestics. This historical method has been given new life in the digital age and with digital records for tracing individual lives (Stone 1971; Carney 1973; Ankoud 2020). Digital humanities scholars have revolutionized this method through the use of big data, linked data, and network analysis to examine larger groups and ever larger datasets to find patterns and connections within and in between groups.

My study on English Enlightenments draws on a dataset constructed with Claude Willan of Rowan University, Dan Edelstein of Stanford University, and Willan’s research assistants. Our dataset includes just over 2,100 correspondents of major Enlightenment figures of English nationality, extracted from the Electronic Enlightenment’s database of “lives” of Enlightenment authors and their correspondents and filtered for the nationality “English” or for birth in England. This data is then enriched with data from academies, colleges and universities, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, VIAF, and other DH projects which use the same prosopographical model to add the correspondents to other sets, networks, and demographic groups. The method for marking-up and linking data is described in our group’s article on the French Enlightenment (Comsa et al. 2016) and uses a modified version of Procope, a schema for marking up early modern and eighteenth-century European prosopographical data.

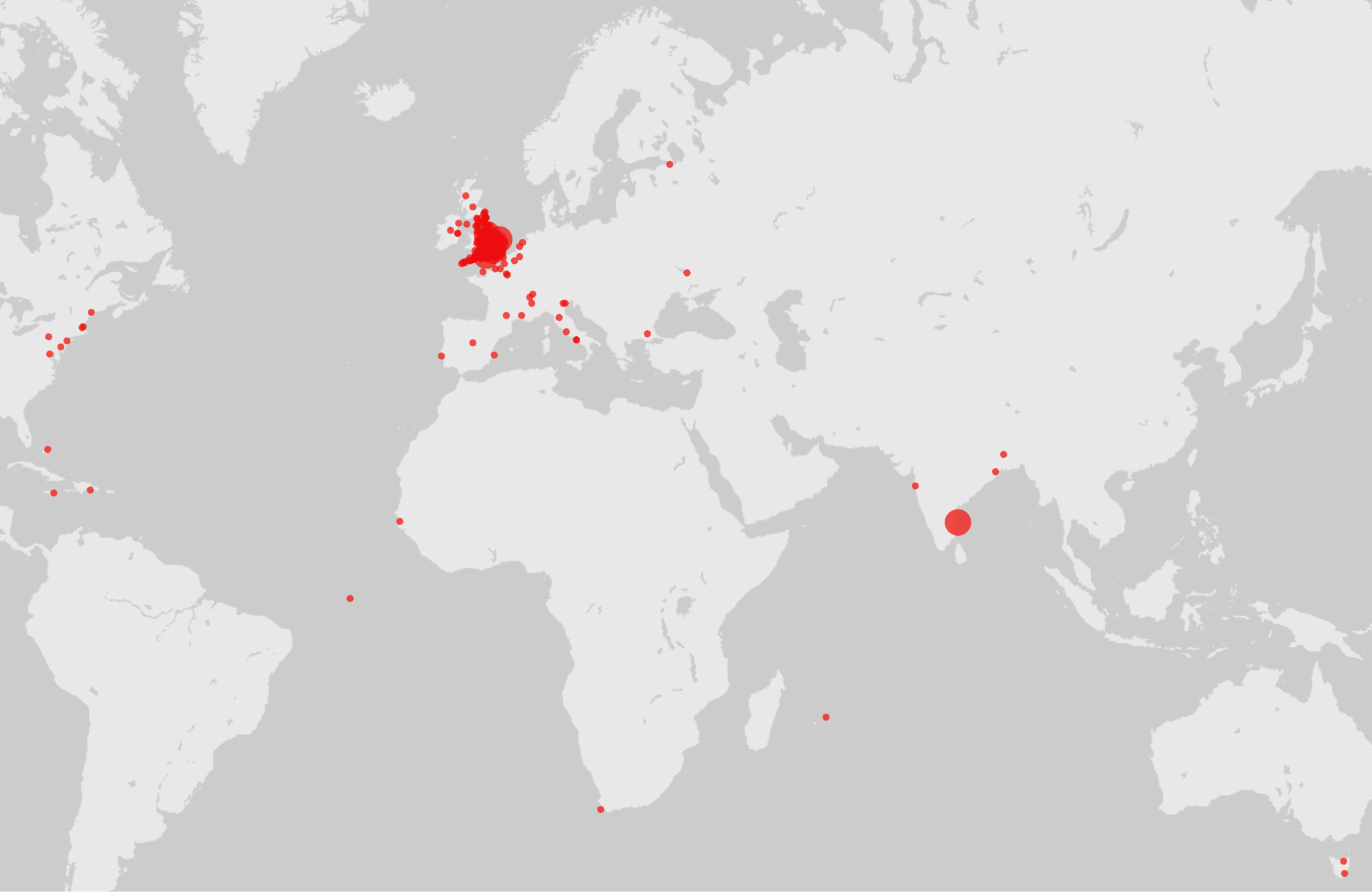

While the global Enlightenment has been treated extensively both in relation to colonialism and the development of capitalism (Gies / Wall 2018), the prosopography underscores just how much the English Enlightenment extended across both time and geography, with deaths in India and continental Europe particularly common among English correspondents. Of the 2,003 persons with a known gender in our dataset, 268 were female and 1,735 were male. I aim to expand the understanding of who participated in the Enlightenment and to include figures who are not often captured in standard histories of scientific and philosophical progress by examining minor and infrequent correspondents.

Figure 1 - Birth places (a) versus death places (b) for English correspondents

By studying the knowledge networks, social networks, educational networks, and demographics of these participants in Enlightenment correspondence networks, we can see which figures and institutions emerged as most central, as well as how the diverse segments of Enlightenment culture interacted.1 We can also see which institutions were most prominent in Enlightenment correspondence networks -- whether academies, universities, specific cities, clubs, salons, or professions.

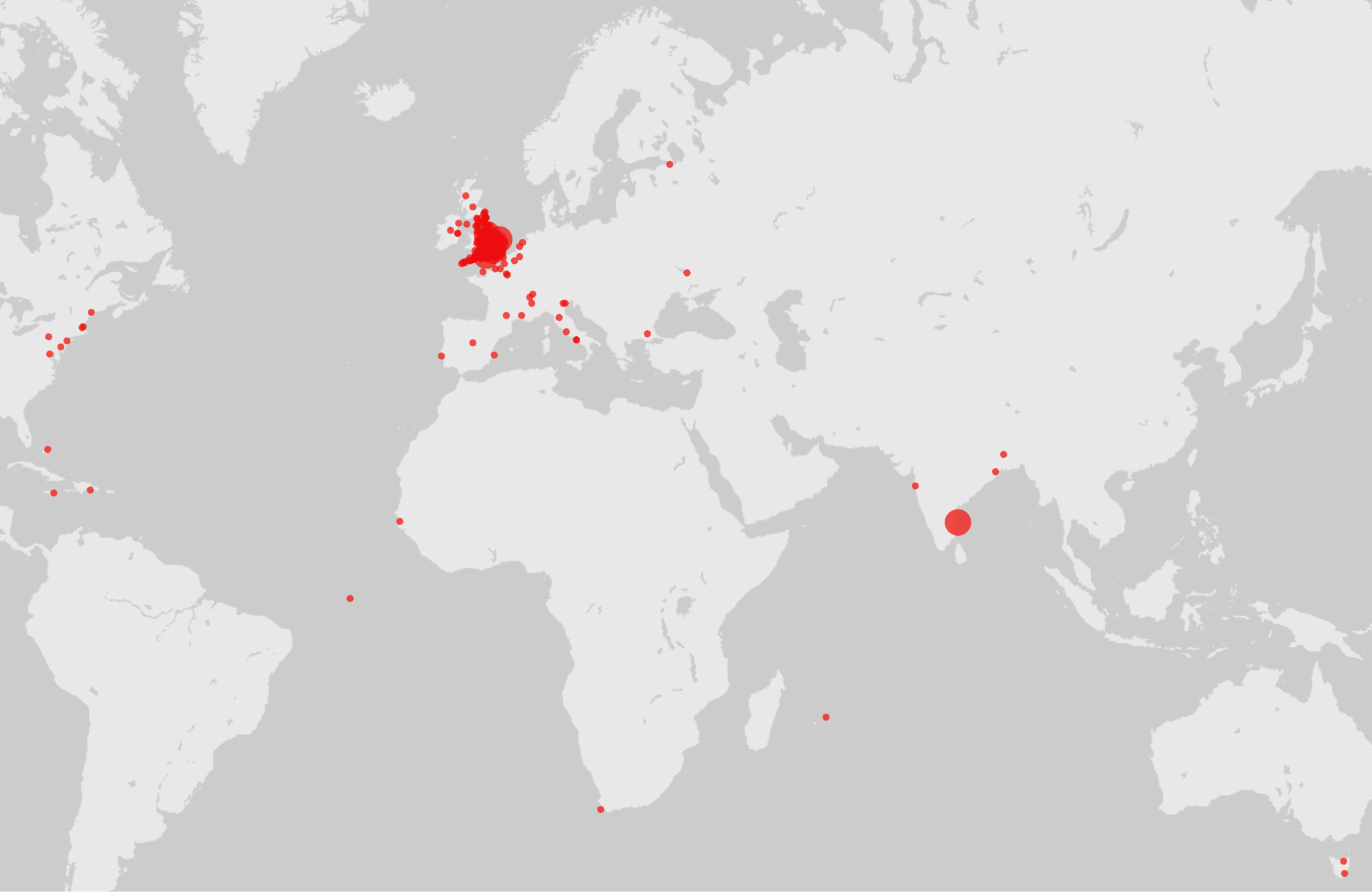

Figure 2 - Birth places for English correspondents (detail)

The correspondents of major Enlightenment figures were born in diverse regions of England with London predominating strongly over any other region. The internal geography of England and its role in the Enlightenment(s) and the scientific Enlightenment are themselves complex topics (Elliot 2010) but that city remains by far the most common birth and death place.

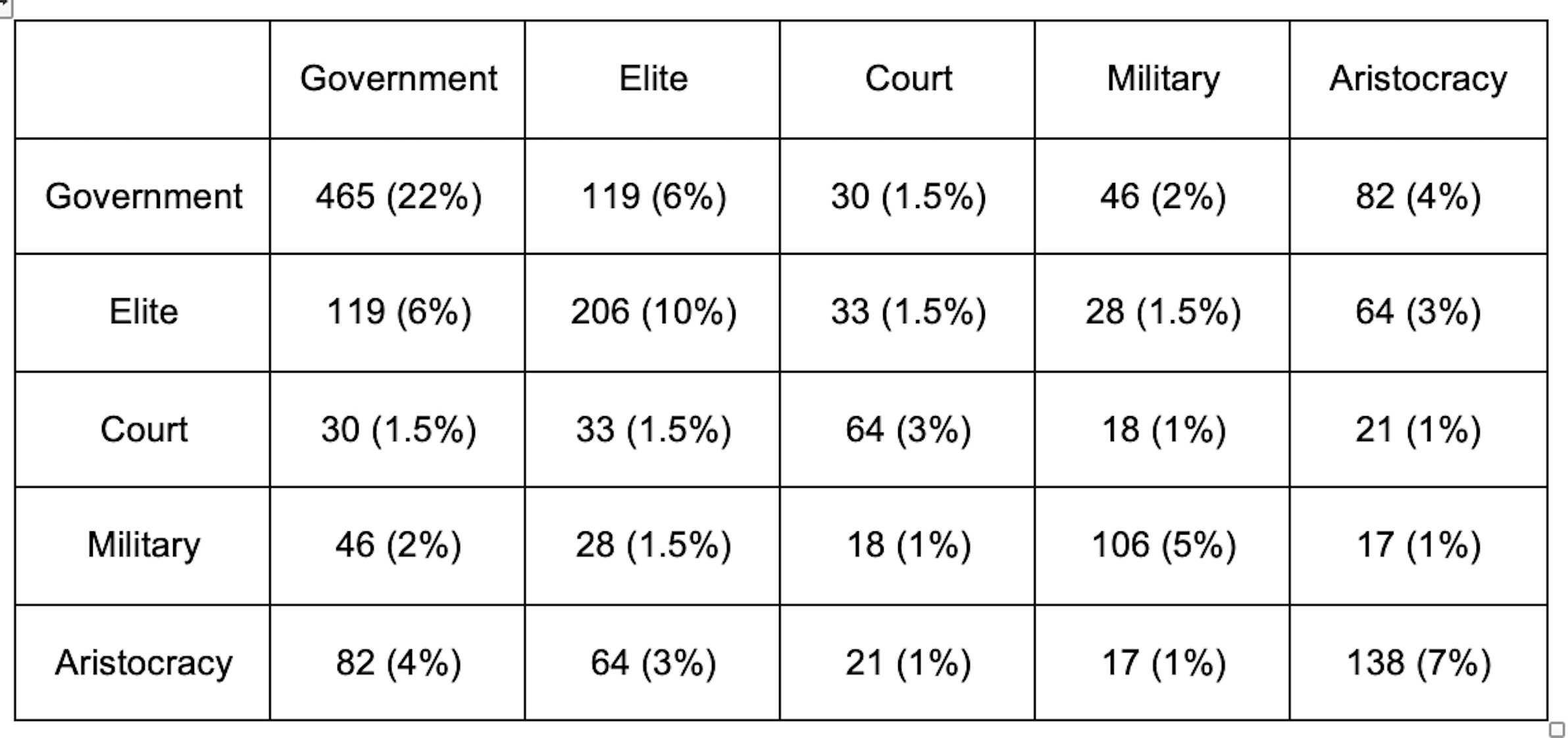

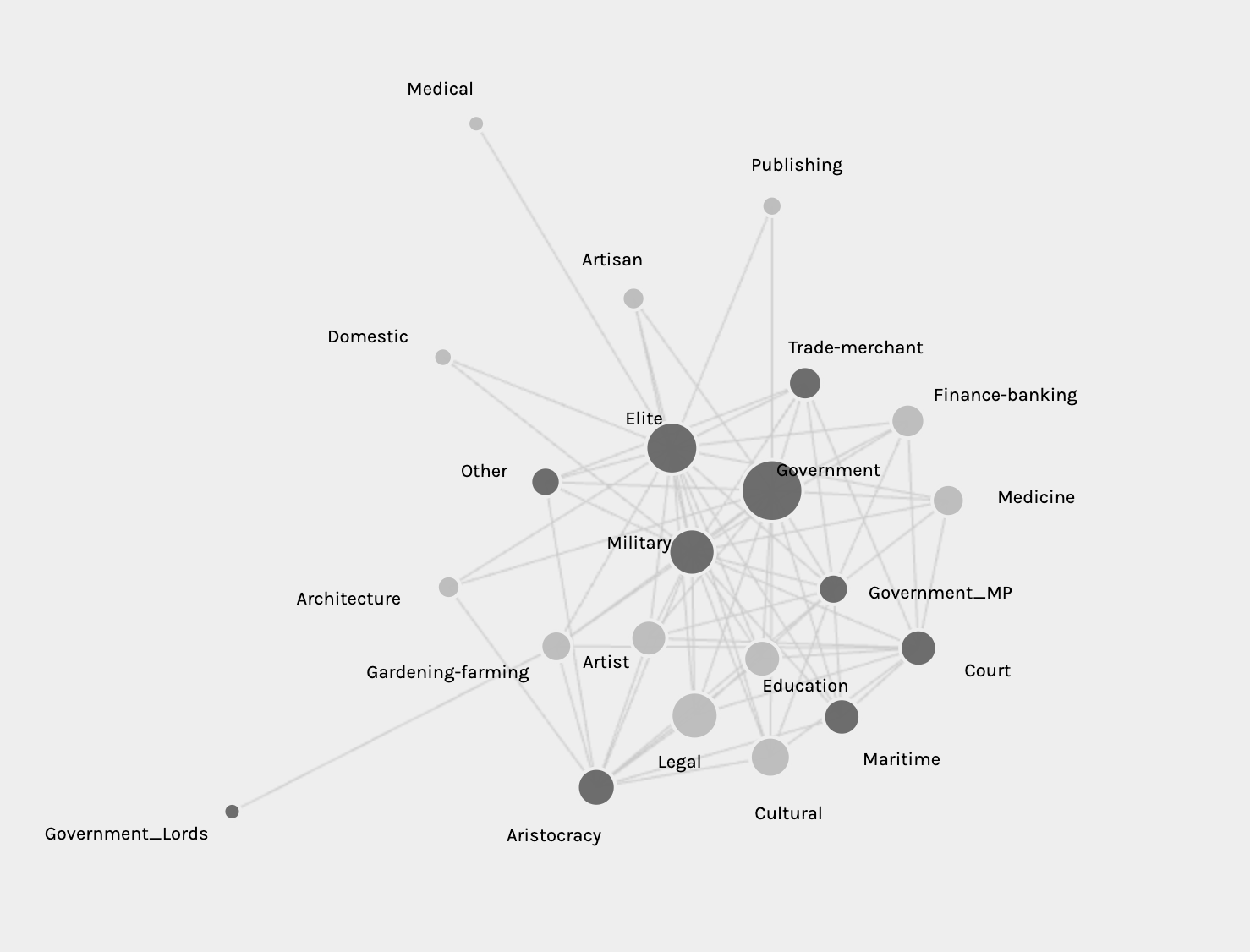

Of all the social networks that I studied, government affiliations (22%) were the most common among these correspondents, much more so than documented members of the court (3%) or the titled aristocracy (7%); people with military roles were also present in somewhat higher numbers (5%), as were members of the gentry and other elites (10%). It is important to bear in mind that these numbers are all minimum numbers, rather than best guesses, because they are based only on documented associations.

Table 1 - Matrix of social networks of English correspondents

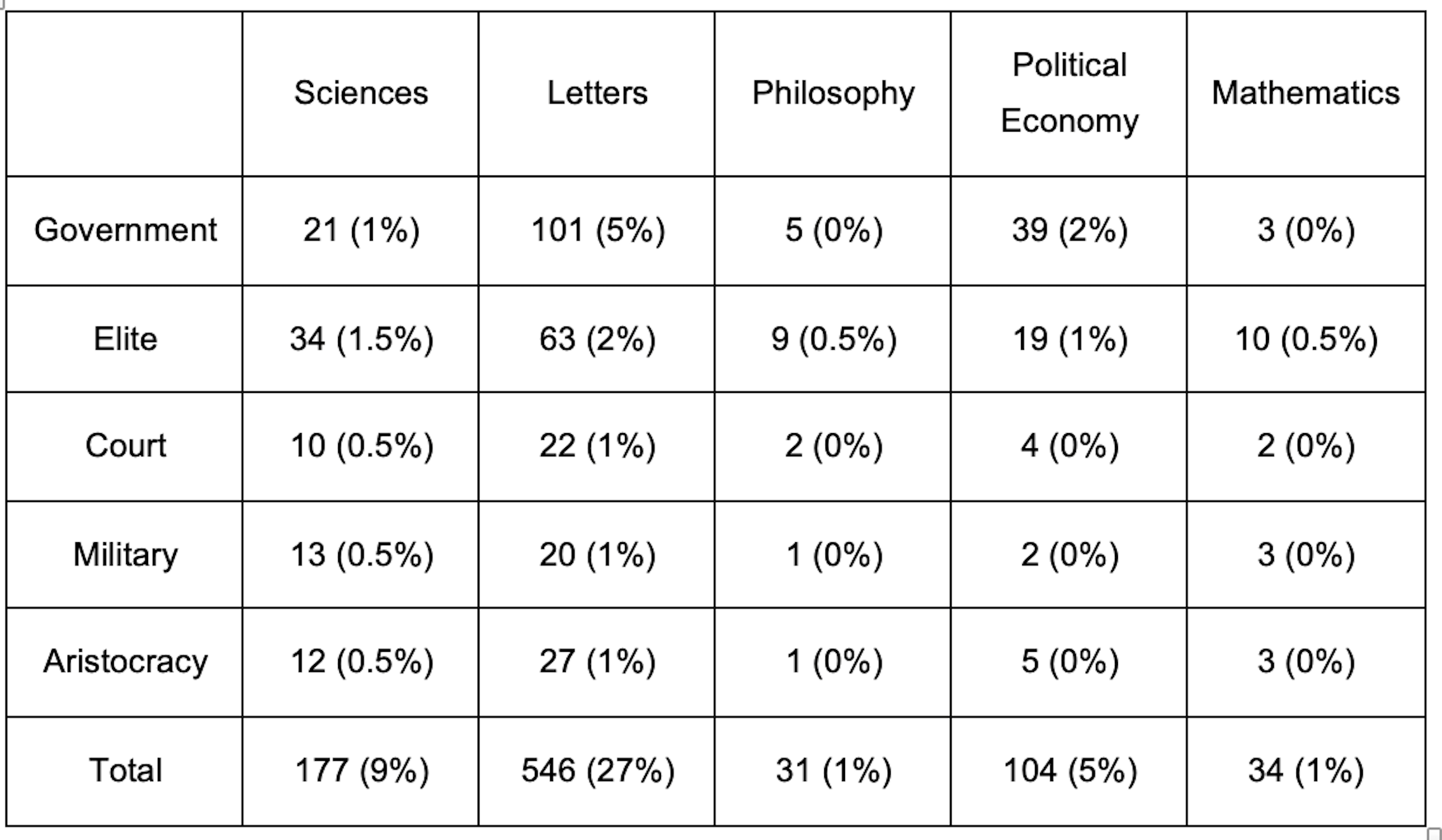

The largest knowledge network among the correspondents is “Letters” (27%), defined as either general-interest writing, or religious, philosophical, or literary writing, each of which has its own sub-category in the data (Table 2); many of these writers worked for the government (18.5%) and/or were members of the elite (12%). Participants in the sciences are also likely to be elite but less likely to work for the government. “Political economy” is also a wide-spread interest and topic for published writings, with 40% of those participants working in government.

Table 2 - Matrix of social networks and knowledge networks as demographics in the correspondents network

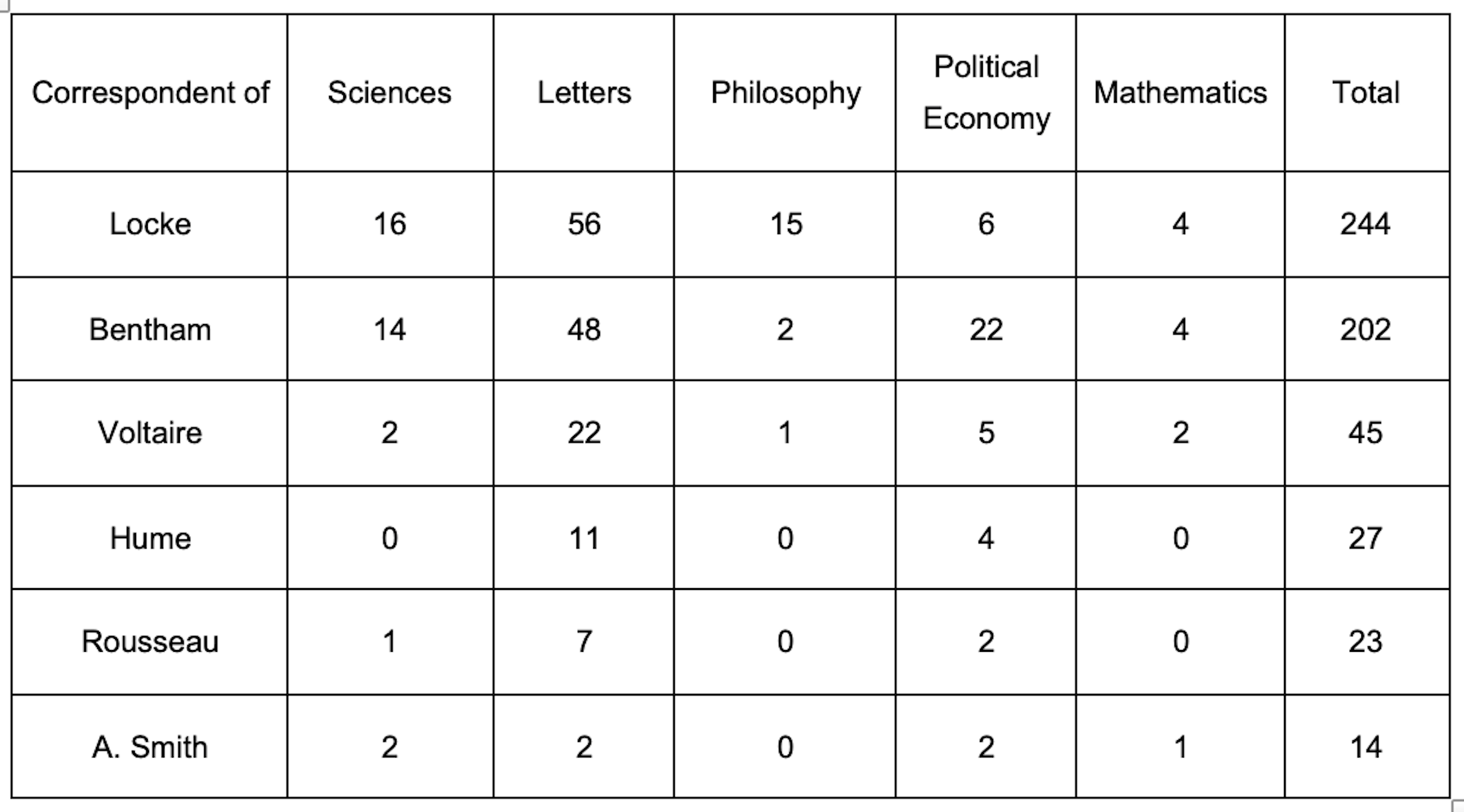

Letters and government affiliations remain central in the correspondence networks of the major figures of philosophical and scientific Enlightenment. Even among the correspondents of philosophers like Locke and Bentham (Table 3), “Letters” is more common than philosophy or political economy as a documented interest of the correspondent. The appearance of letters across so many different parts of the sub-network suggests that these correspondents are socially sorted, rather than drawn together by quasi- or proto-disciplinary interests, one feature of Enlightenment mythologizing that appears to be supported here. For example, Eighteenth-century English philosophy, hardly a unified school, is often remembered as having been more unified than it actually was (Frasca-Spada 2001).

Table 3 - Matrix of social networks of English correspondents by Enlightenment figure

The preeminence of government connections within this correspondence network means that other professional networks are most often linked through government employees or politicians. In a bi-partite network of social networks and professional networks (Figure 3), we see that “Government” and “Elite” once again occupy the central space and the court and aristocracy are less central. The aristocracy is more likely to be linked to legal, cultural, or artistic networks than to publishing, medical employment, or finance and banking. This tendency is hardly surprising from a cultural perspective, as aristocrats chose some professions over others, but it shows how government networks may have come to take on such a central role in these correspondence networks, given the tendency of those in government to engage in other professions or to be elected to government after another career.

Figure 3 - Social networks in a bi-partite network with professional networks

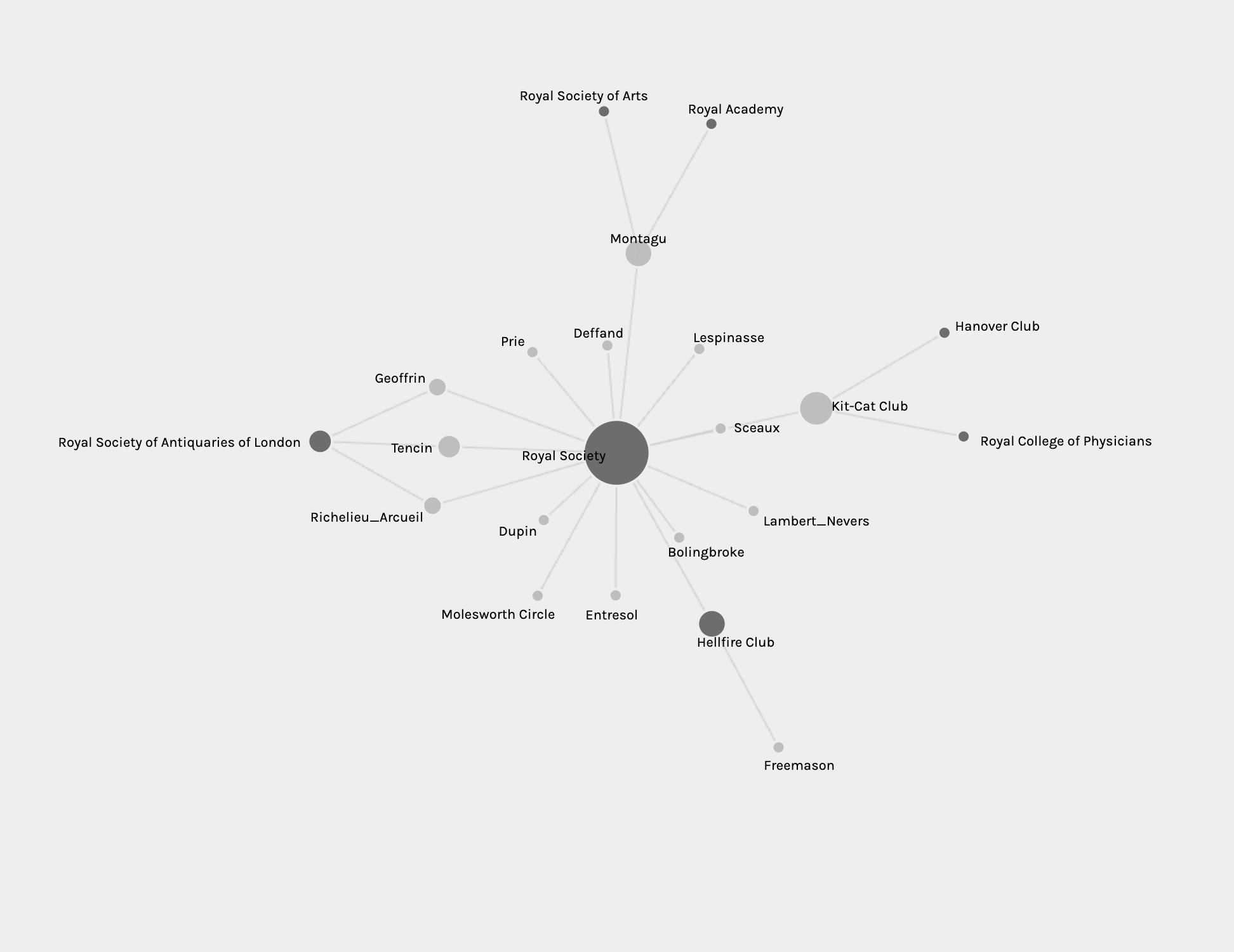

When mapping out connections between clubs, academies, salons, and other face-to-face meeting places, we find that the Royal Society occupies a similar place as government in the English correspondents network (Figure 4). There were 207 members of the Royal Society in our data, making it one of the most central hubs of Enlightenment in England. The Royal Society is one of the most enduring and central subnetworks of English Enlightenment networks (Figure 4). Founded in 1660, the Royal Society did not have a set number of members and was active throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, bringing together both participants in the scientific Enlightenment and later participants in the cultural and philosophical Enlightenments of the eighteenth century.

Figure 4 - Academies in a bi-partite network with clubs and salons

Among these diverse threads, there are central themes that re-appear in the data: 1) the presence of London as both birth and death place of correspondents, 2) Oxford and Cambridge as uniting centers for those born outside of London, 3) the continued relevance of the Royal Society and its many connections to social clubs, academies, and Continental European institutions, and 4) the role of government employment in tying together diverse social and professional networks. From these patterns, we can see that government and elite universities connected the various elements of the English Enlightenments far more than professional or knowledge networks did. English Enlightenment networks were much more bourgeois and less aristocratic than one might imagine given the central role of the Cavendish and other noble families in the social networks of the era.