1.

Introduction

This research looks at the individual works of 20th century library scholar S.R. Ranganathan, and the current core competencies for Library and Information Science (LIS) education as published by the American Library Association (ALA), in relationship to one another. Using data analysis tools, as well as historical research, we pinpoint overlaps in the themes of these two sources, and are developing an in-depth analysis of the historical, pedagogical, and theoretical aspects of librarianship as addressed by Ranganathan over his career, as well as where and how Ranganathan’s work speaks to, inspires or is inspired by the “normative”— that is, prescribed by the ALA— definitions of librarianship and its themes, tools, and professional expectations.

2.

Background

2.1.

Ranganathan

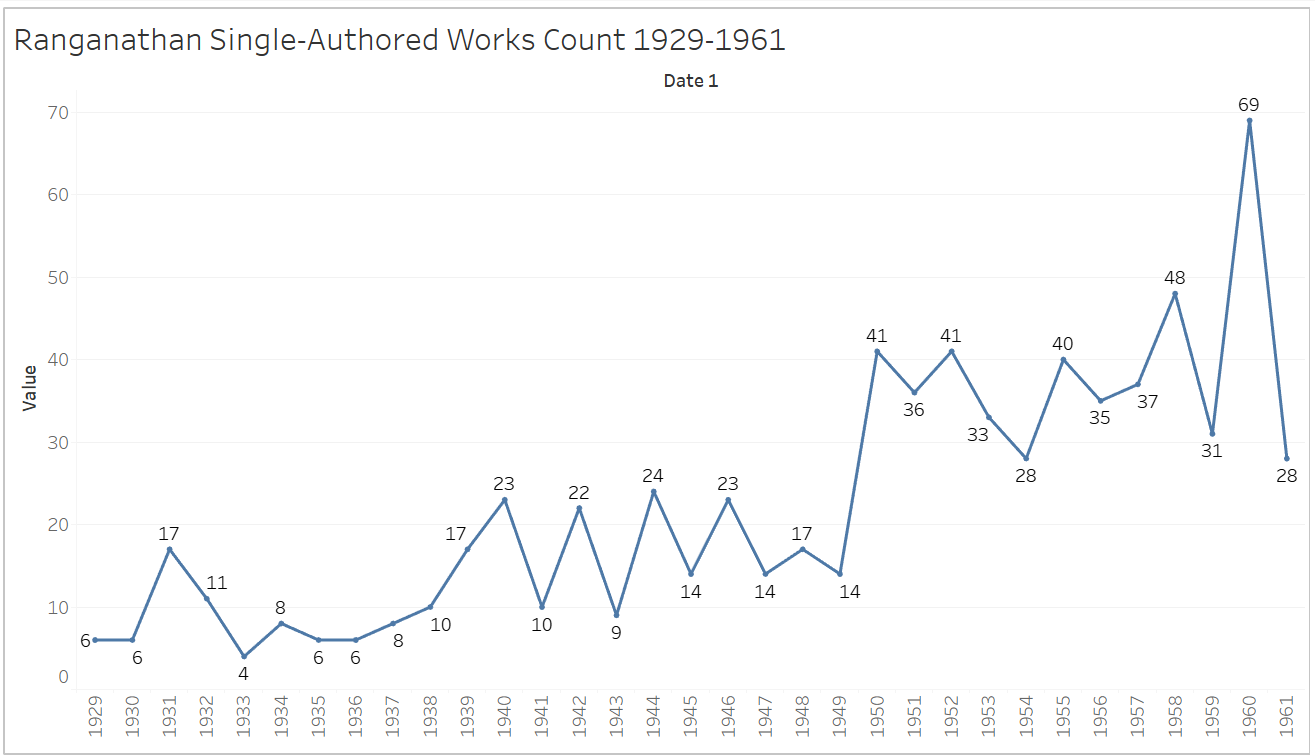

Shiyali Ramamrita (S.R.) Ranganathan, 20th century Indian Library and Information Science scholar, remains highly recognizable within the world of LIS. As a scholar, Ranganathan wrote so prolifically during his life, and that writing was so well-documented, that we are able to interact with his work at a scale usually reserved for larger genre analyses. Nearly 1,000 individually-authored works in the span of approximately 30 years 1929-1961 means that Ranganthan is essentially a genre/subject unto himself with LIS literature. It is thanks to the diligent documentary work of Ranganathan’s students and peers during his life that we have the extensive data available about his publications and interactions with other scholars, first published as a part of Ranganathan Festschrift, a two volume work assembled for Ranganathan’s retirement in the mid-1960s (Kaula, 1962; Das Gupta 1967).

1

2.2.

ALA

Parallel to the life and career of Ranganathan has been the establishment of the American Library Association, the United States-based organization which provides guidance, standards of practice, and professional support for libraries and librarians in North America. Of particular interest to this study is the ALA’s accreditation of degree-granting library training programs in the United States and Canada.

2

Although Ranganathan was educated in India and the United Kingdom, he was born just 16 years after the founding of the ALA, and the growth and influence of the ALA on global librarianship was establishing itself as Ranganthan entered the profession. He traveled extensively in the US, and crossed paths with Melvil Dewey while Ranganathan’s star was on the rise, and after Dewey himself had been driven from high-level library organizing (Kumar, 1991, Denton, 2009).

3

ALA began accrediting degree-granting library training programs in 1925, and while this research eventually intends to expand into a historical analysis of the ALA accreditation standards and educational core competencies, our current research questions and goals focus on the expectations placed on LIS students today by the ALA, and the historical scope of those topics as discussed by Ranganathan during his career.

3.

Data and Researcher Positionality

This research uses two data sources:

Ranganathan Festschrift, and course data regarding ALA-accredited master’s degree programs in the US and Canada as of Fall 2023, collected and coded by the research team. The researchers are a LIS faculty member who has been enrolled in or working directly with MLIS programs and students for 9+ years, and a graduate student researcher, currently working towards a dual MLIS-MA History degree. We believe that our backgrounds and current roles within the field make us uniquely situated for this cross-analysis of history and pedagogy.

3.1.

Ranganathan Data

The

Festschrift data was digitized by the researchers directly from a print copy of the book, and after data cleaning with Google sheets and OpenRefine, was compared to a bibliography of Ranganathan’s single-authored works also developed from the

Festschrift and posted to the S.R. Ranganathan page on the International Society for Knowledge Organization (ISKO) website (Raghavan, 2019). Initial analysis indicates that the

Festschrift records approximately 250 more entries than the ISKO bibliography, the majority of which are short biographical pieces written for a small-circulation Indian science journal,

Current Science, which Ranganathan served as an editor for for most of his career (Ibid.). We are in the process of reintroducing these citations back into the dataset, in order to better represent Ranganathan’s works in the way that he himself presented them during his life. For the purposes of this project, we are interested in the topics on which Ranganathan wrote, and how those groupings compare to the areas which LIS students are expected to study during the MLIS today.

Figure 1 (above): Number of single-authored works by S.R. Ranganathan by year, based on ISKO data (does not include Current Science publications)

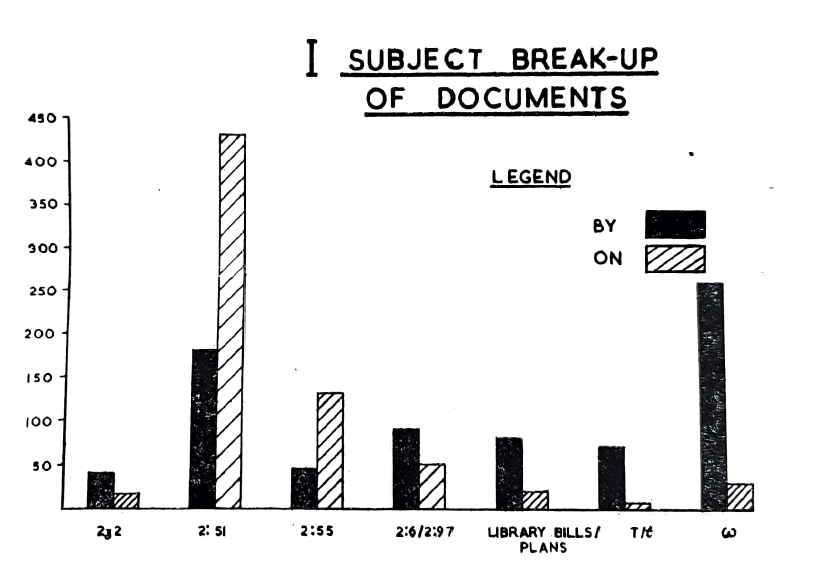

Figure 2 (above): Subject classification of single-authored works by S.R. Ranganathan, and responses to those works as compiled and printed in

Ranganathan Festschrift (Das Gupta, 1967).

The categories of Ranganathan’s publications as determined by the editors of the

Festschrift are as follows, represented from left to right in Figure 2, above.

- Laws of Library Science

- Classification

- Cataloging

- Circulation, Reference & Reference Service, Administration & Documentation

- Library Legislation and Development Plans

- Education

- Biographies (Ibid, p. 13).

Category 7, “Biographies” is by far the largest category by number of documents written by Ranganathan, and represents the biographical blurbs Ranganathan wrote for Current Science over the course of his career. The second largest category, “Classification” is unsurprising, as Ranganathan’s development of the Colon Classification system and theory of faceted classification are considered his largest contributions to the field (Ranganathan, 1933; Rubin / Rubin, 2020). Unfortunately, we do not have access to the original source from which the “ON” data was developed, though parts of it and reference to its development are documented in the

Festschrift, and is intended to document the number of papers responding to Ranganathan’s scholarship.

3.2.

ALA Data

The ALA data was developed from the list of ALA-accredited MLIS programs, available on the ALA’s website (Searchable DB of ALA accredited programs, 2023). This list was imported into a spreadsheet, and additional metadata about each program was hand-coded into the document. This included information about the required core courses for each program, including the course titles, information about required textbooks, course syllabi (if publicly available online), as well as data such as data of initial accreditation, any lapses or changes to accreditation over the program’s history, degrees offered, and links to the program website. Our initial analysis determined that there were not enough syllabi or titles of textbooks available for analysis to yield significant results, and so these data points were set aside for the time being.

The researchers coded the core courses, based on their course title, into one of eight categories based on the core competencies for librarianship as produced by the ALA (ALA Core Competencies of Librarianship, 2022). These categories were:

- Introduction to LIS/Professions

- Technology Skills

- Lifelong Learning

- Serving Diverse Populations (Information Users)

- Leadership & Management

- Research Skills

- Knowledge Organization

- Reference and Resources (Information Objects)

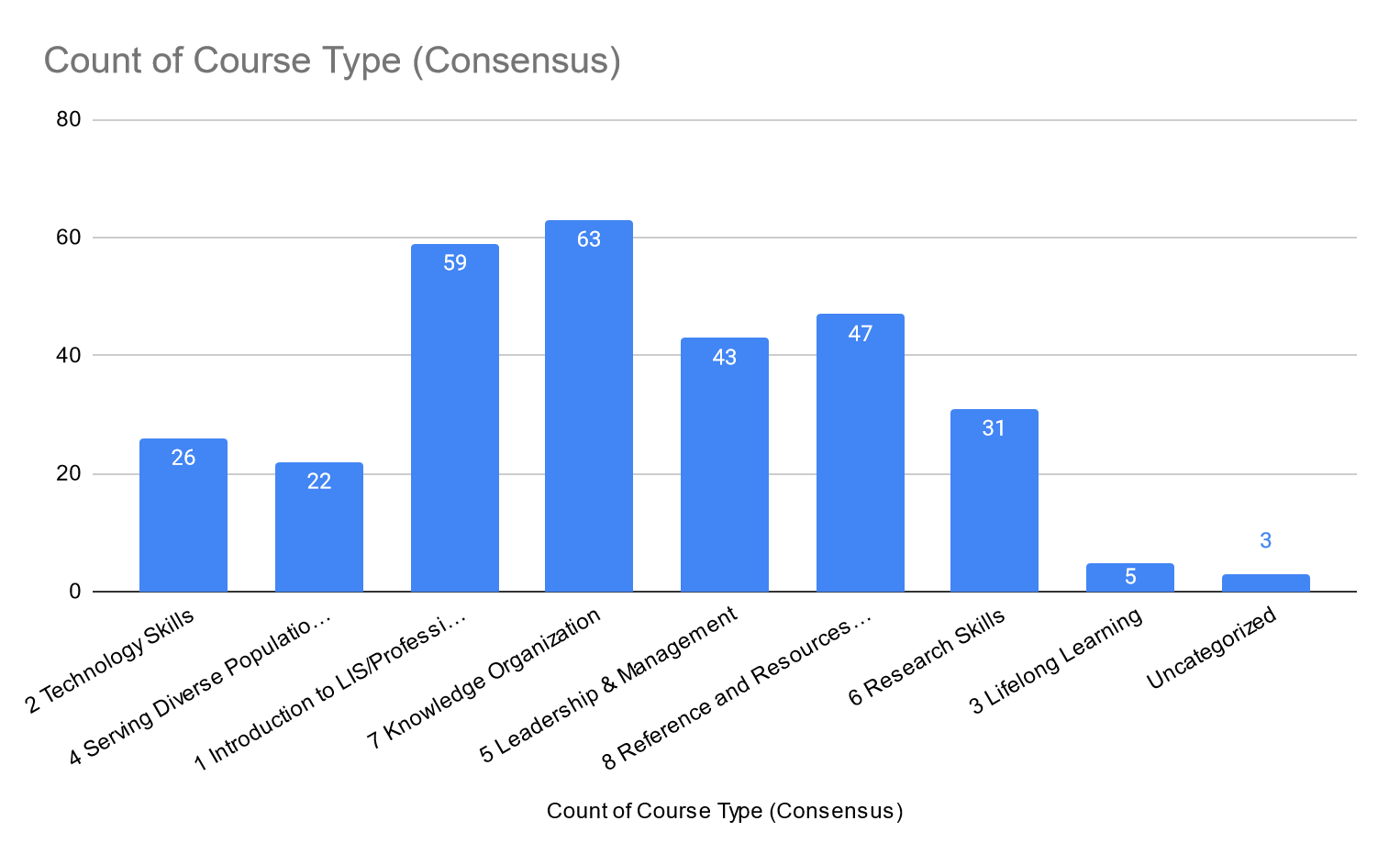

Each researcher coded the core courses on their own, after an initial discussion of the categories to establish a shared understanding of each. Out of the 299 courses coded, the researchers agreed on 268 of the codes, for an initial agreement rate of 89.6%. For the remaining courses, we discussed each individually, each coder was given the opportunity to justify or retract their choice, and final codes for these were made based on mutual consensus between the coders. Three (3) courses were coded as “uncategorized” as these were capstone projects or several courses on rotation under a single course code, making it impossible to make a judgment on the intended content of the course. This coding produced the following results (see Figure 3, below)

Figure 3 (above): Course types of required courses at ALA accredited MLS granting degree programs in 2023.

We chose to focus exclusively on the titles of the core courses for these programs for our coding, as we felt that phrasing and rhetoric of these titles reflected the phrasing of the ALA core competencies, and also presented the first instance in which new student or other outsiders to the field might understand what is expected of a librarian by the ALA, which itself represents the interests of its constituent institutions.

4.

Initial Analysis

The first phases of this research have been dedicated to collecting and synthesizing data in order to facilitate comparative analysis between the two sources. Our initial observations indicate that Ranganathan and contemporary LIS curricula share an overarching focus on classification and other knowledge organization processes. This comes as no surprise, given Ranganathan's own research themes, but perhaps more interestingly is the shared focus on management and administration— divided across the two categories “Circulation, Reference Books and Reference Service, Administration and Documentation” and “Library Legislation and Development Plans” within Ranganathan’s work, and “Leadership and Management” in the MLIS curricula data.

This category, more so than many of the others, focuses on the labor involved in working with libraries as institutions, in contrast to more skill- or subject- focused categories, such as “cataloging” or “reference.” This is interesting, because Ranganathan is mostly remembered for his more theoretical ideas, and courses and conversations around library management are often considered a newer addition to LIS discourse (Eatman, 2000). Our research indicates that this timeline may be ordered differently than we commonly imagine. Finally, we notice a significant absence of courses in ALA-accredited programs today which address the historical aspect of our field, either as a profession or an intellectual pursuit. While Ranganthan’s works are not coded explicitly into a history-focused category, we note that his consistent engagement with the history of science through his 250+ biographical blurbs demonstrates a practical dedication to engaging with the history of scholarship more broadly.

5.

Limitations and Next Steps

We acknowledge that the current state of this work represents a surface-level analysis of both Ranganthan’s work and the coded LIS courses, and many nuances of form and topic are flattened by this analysis. Future steps in this project include coding of secondary categories for LIS courses based on course descriptions and/or syllabi, as well as additional topic coding of Ranganathan’s work by the research team, as we have relied on the categorization choices made by the authors of the

Festschrift. In addition to analysis of contemporary LIS programs, we also intend to expand the scope of this work to include the analysis of historical LIS courses and program requirements.

Our research demonstrates both the depth of LIS research over the past century, as seen through the lens of a single scholar, as well as the demonstrable lack of education around the history of the profession of librarianship and the field of LIS more broadly. Additionally, by digitizing and expanding the bibliometric analyses of the

Festschrift, we aim to bring the work of the scholars who originally compiled it to a modern, global audience in order to begin the process of re/establishing a more global perspective on LIS research and library work. By pairing the themes of Ranganathan’s work with the Core Competencies for Librarianship as outlined by the ALA, we highlight the areas where Ranganathan’s work moved the intellectual conversation as well as the pedagogy in the field forward, as well as the gaps in contemporary LIS education when it comes to the history of the field.