1.

Introduction

The aim of the paper is a partial and explorative quantitative reconstruction of a literary canon. Canon is understood as the body of literary texts and authors that are considered particularly valuable, important or influential by a group of people who are interested in passing them on (Winko 2002: 19). Texts are not canonical

per se, but are

made canonical by various actors belonging to different groups and institutions. Theorist Simone Winko describes this process using Adam Smith's metaphor of the

invisible hand: Many actions on a micro level not necessarily intending the canonization of an author, together lead to it on a macro level (Winko 2002). At the same time, those actions can serve as an indicator, in reconstructing canonicity at a certain time. In accordance with canon theory, it can be assumed that there is not one, but several canons, which differ, among other things, in the institution to which they are linked, for example schools or universities.

Reconstructions of canon can be therefore categorized according to which canon, in which time period, they deal with and which indicators they use (Kampmann 2013). In

Computational Literary Studies, various indicators have been used in such reconstructions.

1

In this paper, I am concerned with the current

academic canon of German-language literature. I use an indicator that has hardly been explored quantitatively so far:

2

The study of authors in university courses. As an indicator for which authors are covered, I consider mentions of them in course descriptions.

2.

Data and Methods

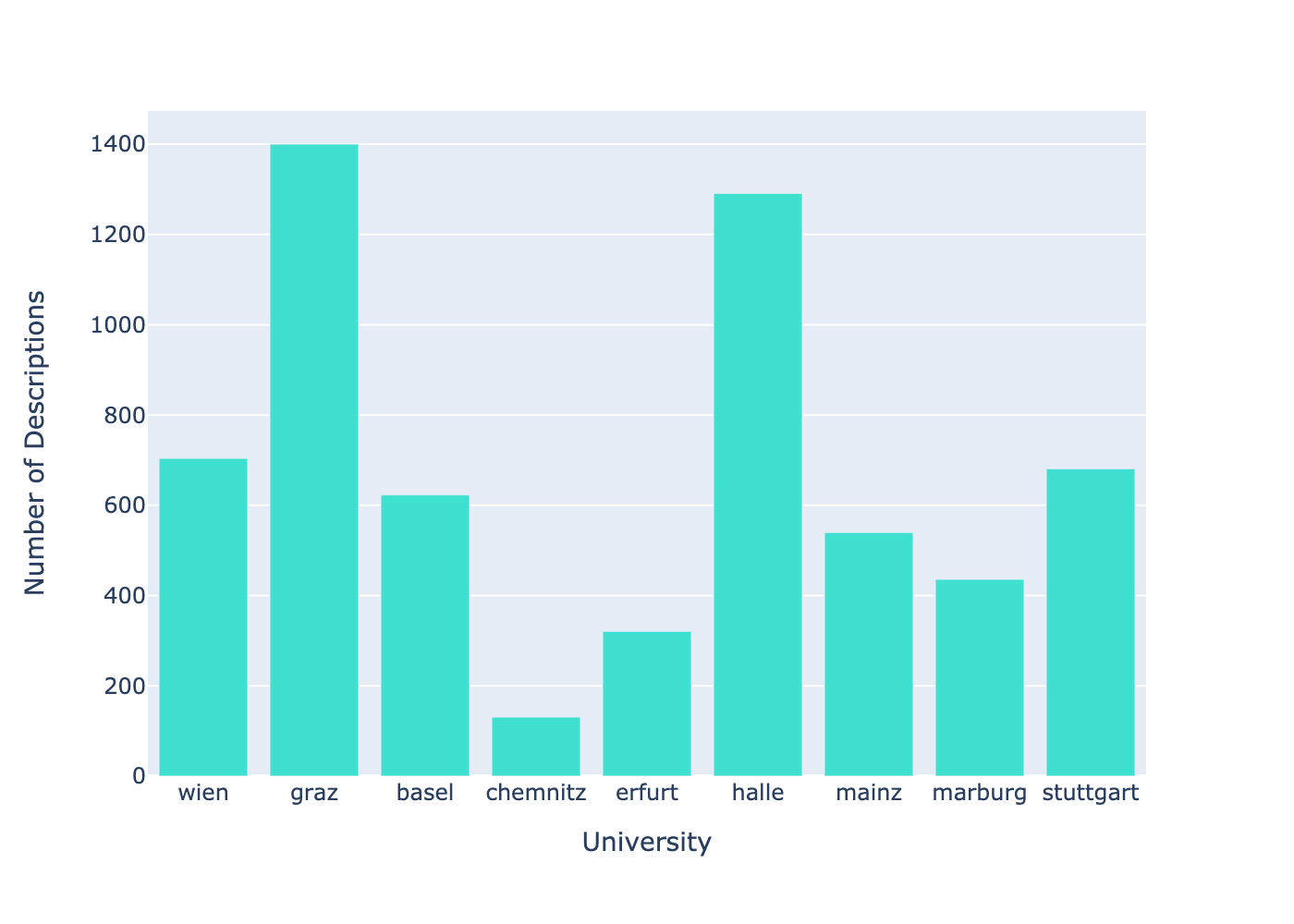

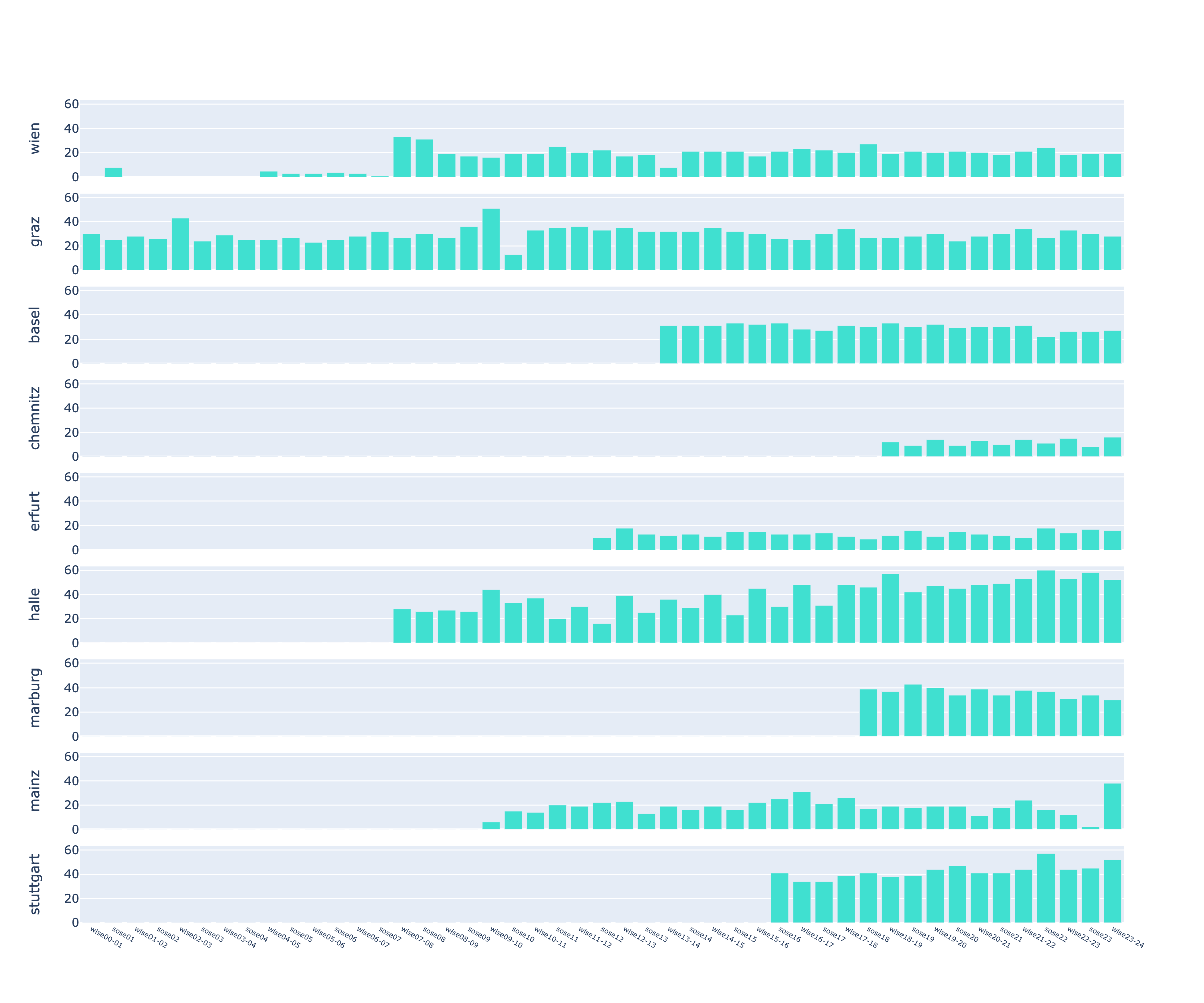

Six German, two Austrian universities, and one Swiss university were randomly chosen. A total of 6127 descriptions were then scraped from online catalogs for courses in German Literature. Figure 1 illustrates the quantity of descriptions per university. Figure 2 shows the quantity of obtained descriptions per semester and university.

Since the data is distributed unevenly across time (s. figure 2), only descriptions from between 2018/19 and 2023/2024 are used for the explorations.

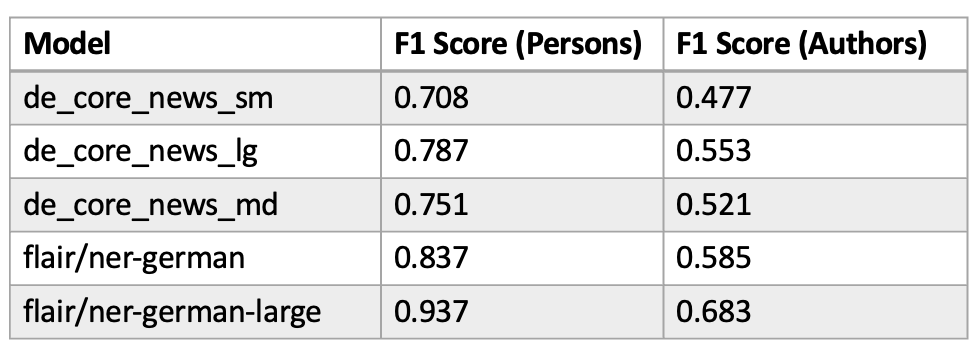

Named entities (NEs) that refer to people and, as a subset, to writers were manually annotated in 54 randomly selected descriptions. Five models were then evaluated (see figure 3). Subsequently, the best performing model was used to annotate a total of 7689 NEs in all descriptions.

Since not all references to people refer to writers, the identified entities were linked to the ‘Gemeinsame Normdatei’ (GND). For the following analyses, taking the metadata from the GND, only entities belonging to writers (total of 1845) are considered.

3.

Explorations

Nation and gender have often been described as relevant factors in canon formation (e.g. Heydebrand/Winko 1994, Starre 2013). For German-language literature, differences between German, Austrian and Swiss Canons could be expected. In the following, the data is explored regarding these categories. The underlying assumption is that the more often an author is mentioned, the more canonical they are.

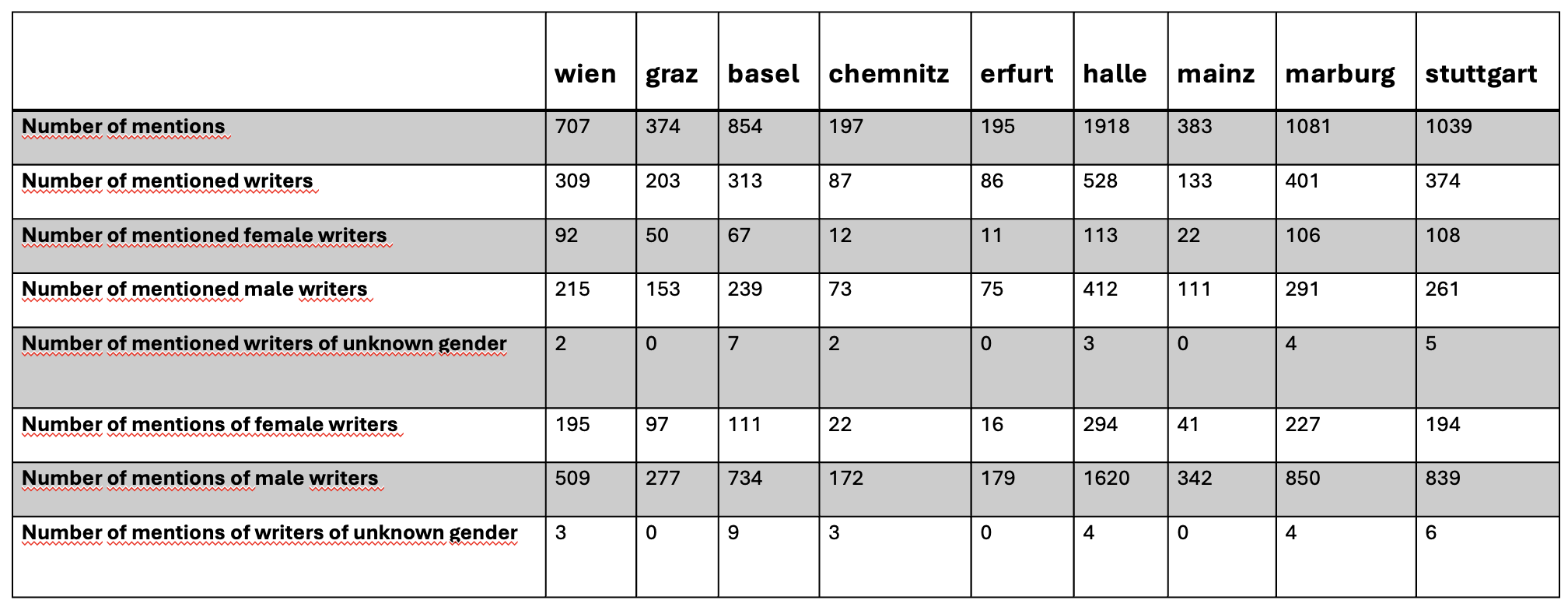

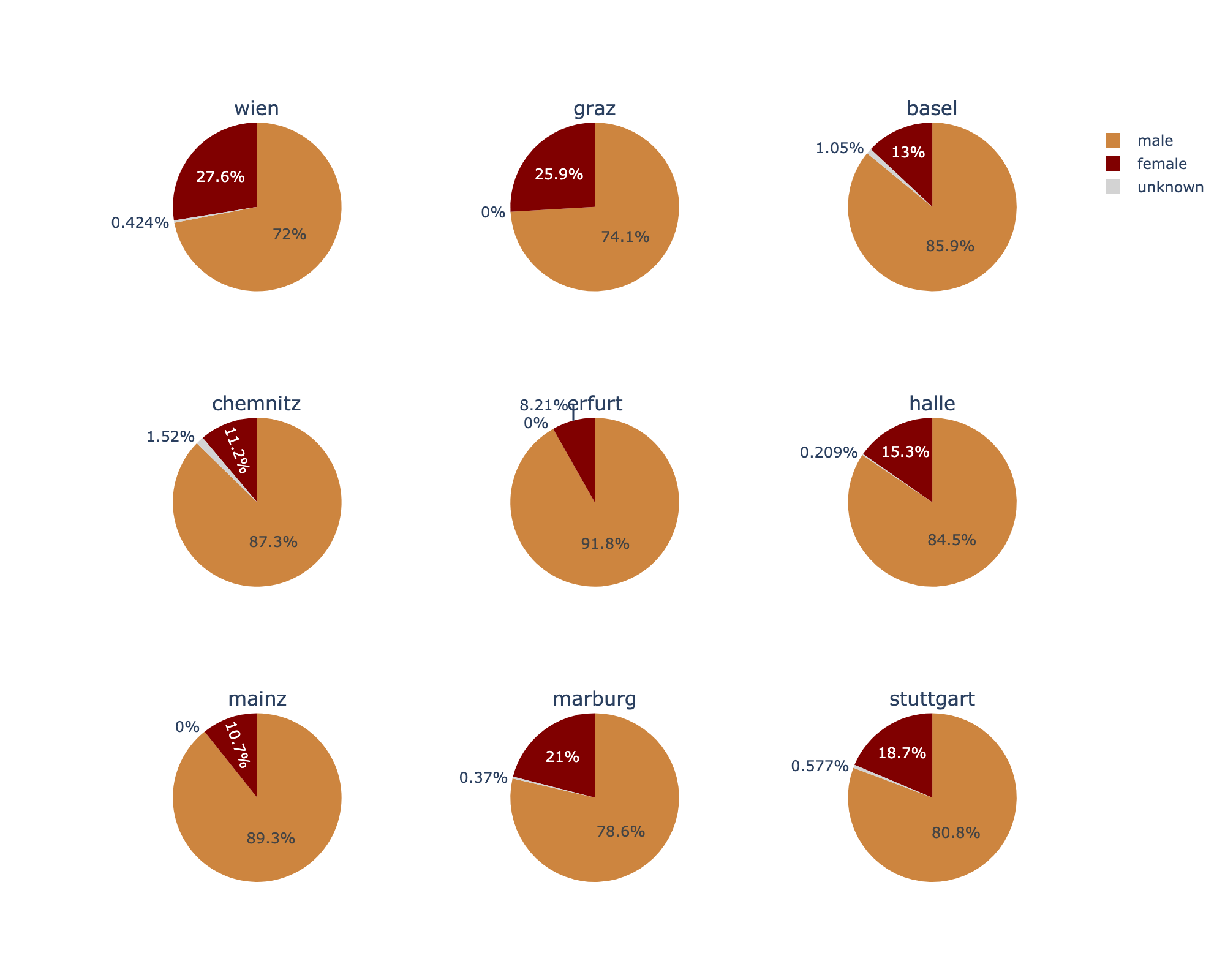

The table in Figure 4 shows the number of mentions and mentioned writers per university. Figure 5 shows the shares of all mentions per university by gender. An assessment of these numbers raises the question of a suitable benchmark. Compared to the expectations of a modern society that strives for equality, the proportions of female writers seem, with a mean of 16,8%, very low. For historical periods in which women did not have equal access to education and were not working as writers in equivalent numbers, however, a different ‘baseline’ would probably have to be applied. This paper, which sees itself as descriptive, cannot set this benchmark. It must be chosen by the universities according to the aims of their programs.

It is striking that the proportion of women at Austrian universities (

wien and

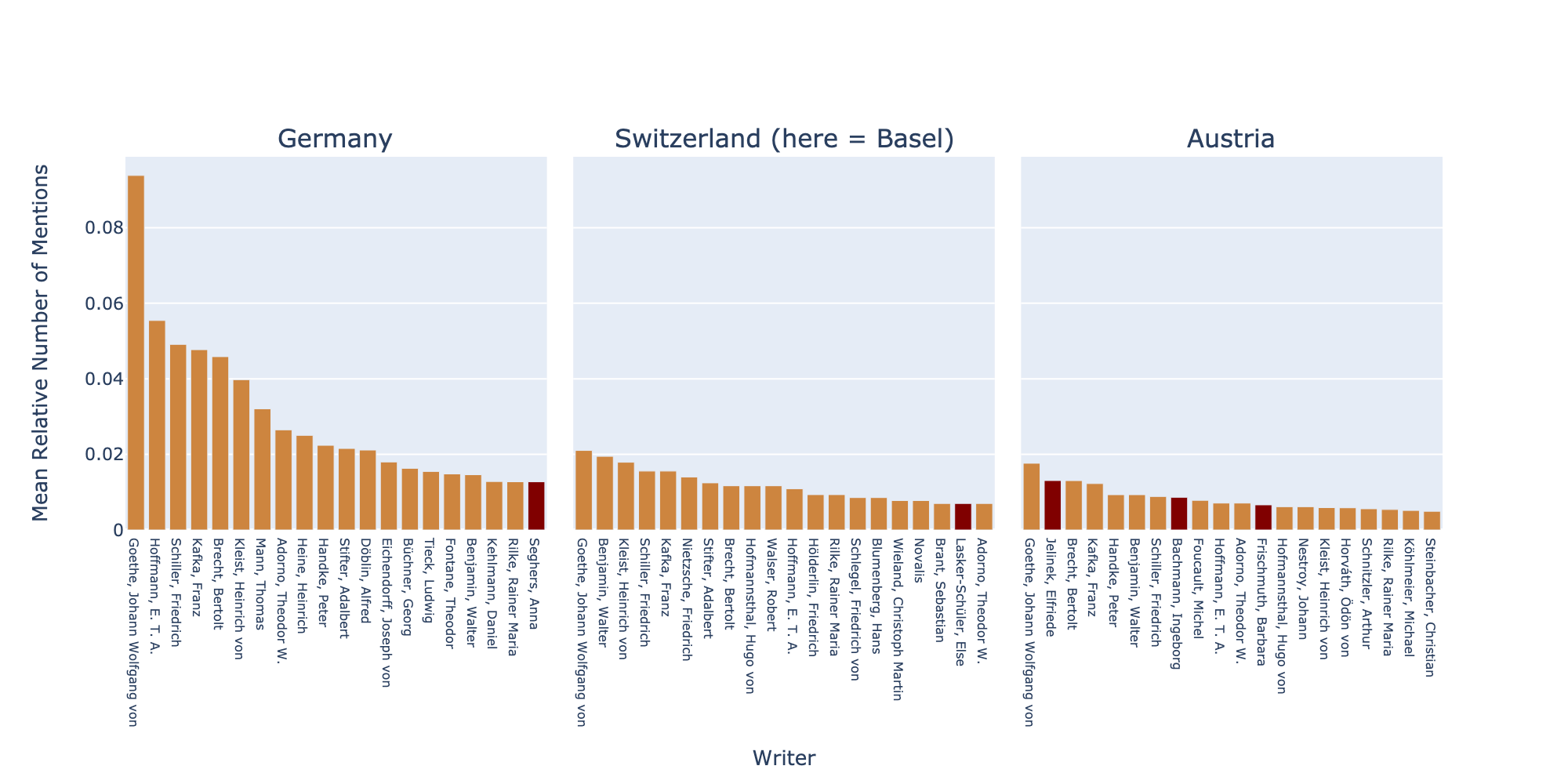

graz) is higher than at the other universities. Figure 6 shows the 20 most frequently mentioned writers per nation.

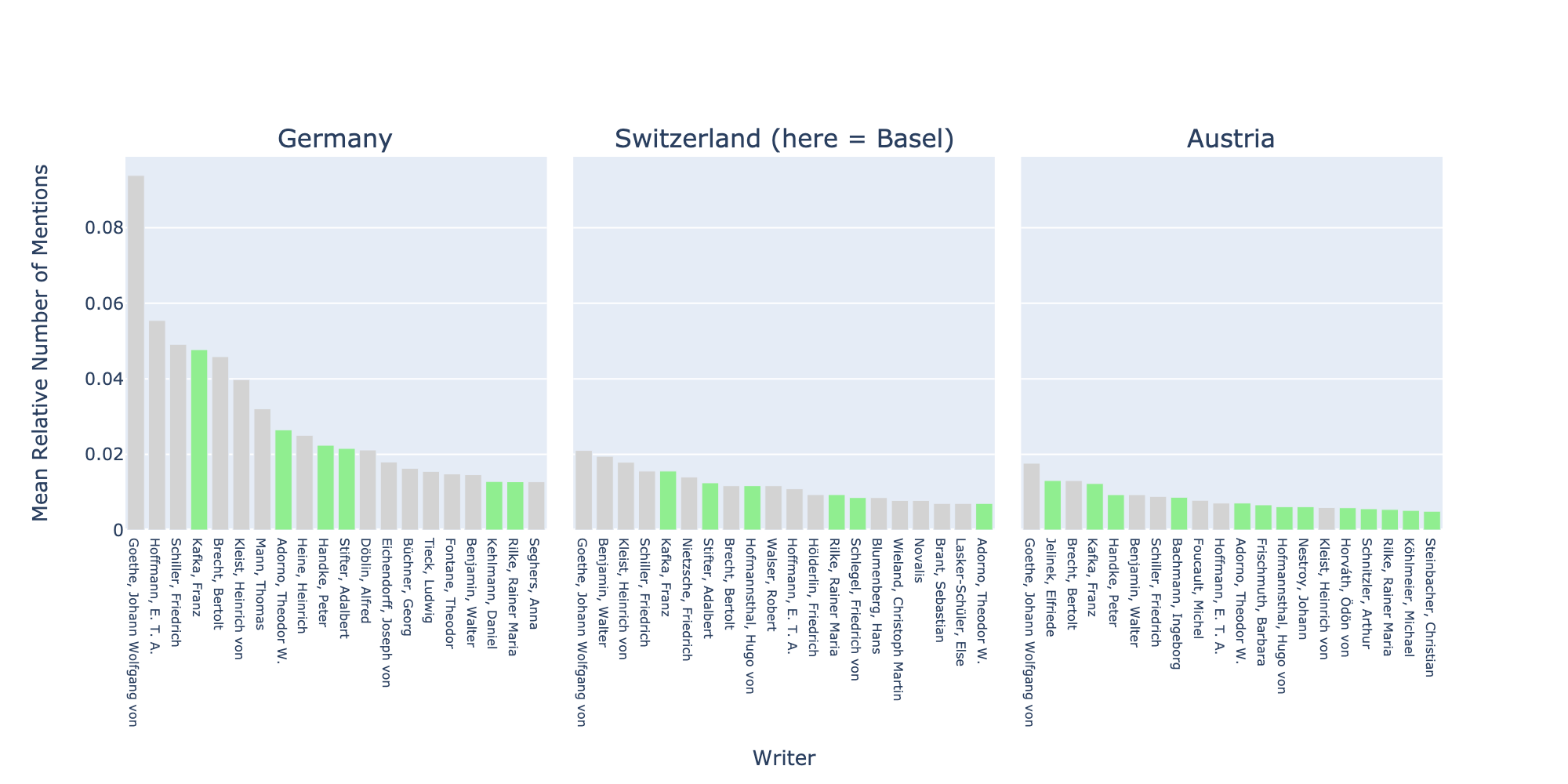

While at the German and Swiss universities there is only one female writer in the top 20, in Austria there are three. And with Elfriede Jelinek, one female writer even occupies second place. Like the other two, Jelinek is Austrian. When the graph is colored according to whether Austria is or was one of the writers countries of residence (Figure 7), it is clearly visible that the Austrian academic canon differs from the others in that it covers more Austrian writers.

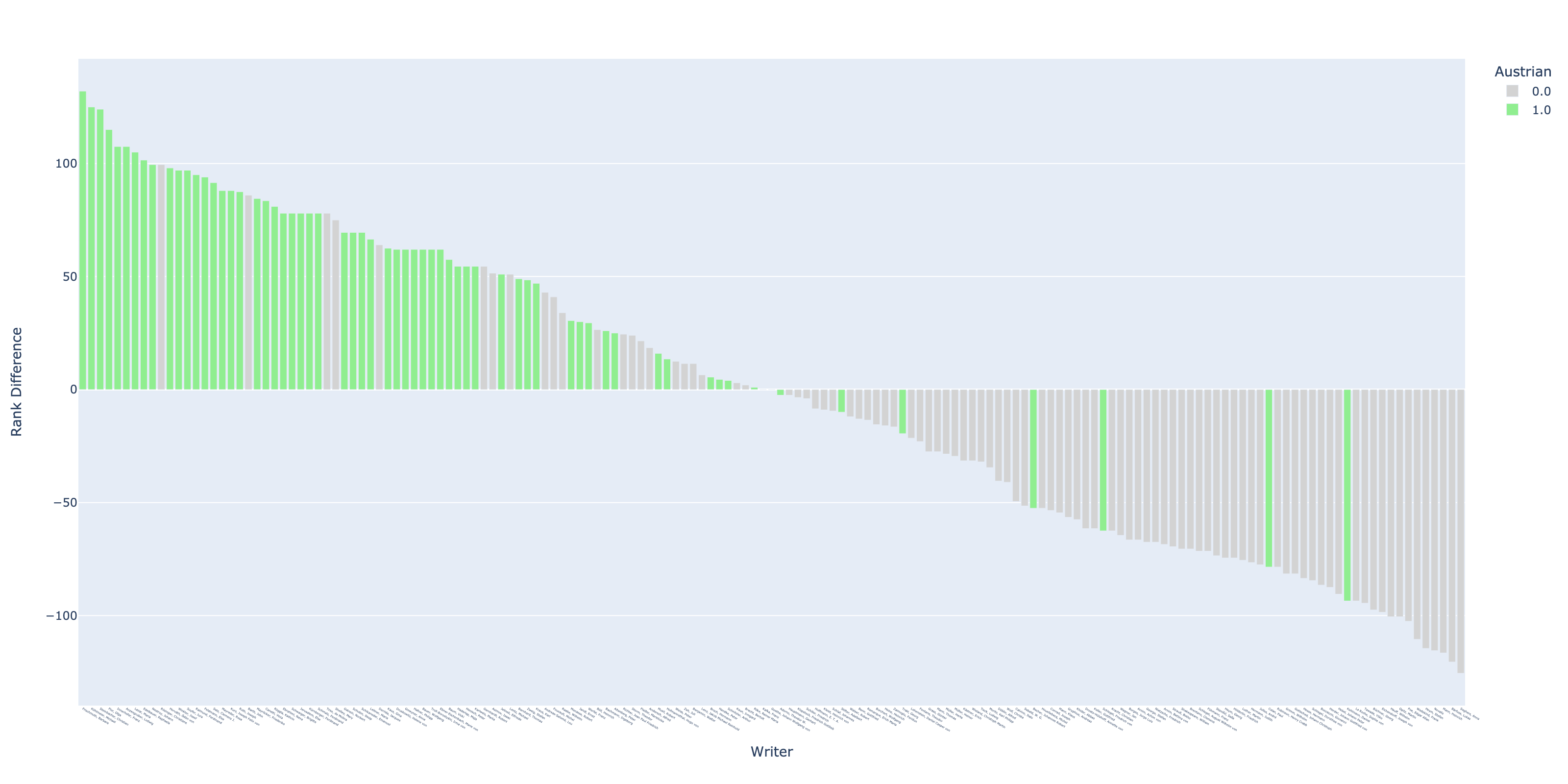

Finally, Figure 8 shows the rank differences between the Austrian and German top lists of 100 writers with most mentions. The accumulation of green bars on the left-hand side, which again stands for the writers’ Austrian place of residence, shows that the writers who are treated much more frequently in Austria than in Germany and thus occupy a higher rank, are primarily Austrian writers.

4.

Conclusion

The data described shows which writers appear how frequently in course descriptions of German studies courses in a randomly selected but non-representative sample of universities. This data is meant to serve as an indicator for academic canonicity.

The explorations empirically support the assumption that there are differences between the national canons. The Austrian courses differ from the others, especially in that they cover relatively more female and more Austrian writers.

In the future, the data can serve as one building block in reconstructing and describing academic canonicity in order to describe corpora or further investigating canon formation.