1.

Introduction

AfricanCalifornios.org aims to reconstruct the African and Afro-descendant presence in Spanish and Mexican California using data science and user-friendly visualizations. Scholars and the public readily accept that Afro-descendants populated Spanish and Mexican California, though little work has been done on the topic. Often cited is the 1790 census of California’s four presidios, San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco, and its two struggling towns, San Jose and Los Angeles, which identifies roughly 19% of their populations as being of African descent. Afro-descendants themselves, however, attempted to eliminate their presence from many vital records. The ambiguity around their locally recognized racial status gave them the opportunity to raise their social position under the anonymity that distance from the centers of political power in Madrid and Mexico provided. They used the government’s desire for Hispanicized settlers and willingness not to inquire too deeply to overcome their perceived inferior origin that elsewhere barred them from entering the higher echelons of society. As a result, African Californios were able to build viable, mutually aiding communities that could only exist in a borderland region like California. Indeed, by the end of Mexican Period (1848), California was governed by a well-known Afro-descendant, Pío Pico.

Figure 1. Masthead of AfricanCalifornios.org featuring Pío Pico, his wife María Ignacia Alvarado, and two nieces.

2.

Background

The most closely related project to ours in terms of subject is the Early California Populations Project (ECPP) database (ecpp.ucr.edu, Hackel and Reid, 2006, 2022). The ECPP contains sacramental records for most of Spanish California. While the scope of the ECPP is large, it is only a database without visualizations of the data. As a result, it is more useful for professional historians, demographers, and genealogists. A more approachable digital humanities project, similar to our approach is found in Slavevoyages.org (Borucki, et. al., 1999, 2008, 2015). This multi-generation scholarly project initially started as a massive database (on CD-ROM) of all the voyages of slave ships from Africa to the Americas. It currently has visualizations of the movement of slave ships from Africa to Americas and within the Americas that have been featured in popular publications such as Slate.com (Kahn and Bouie, 2021) and is currently being used in K-12 classrooms. We are aiming for this project to have a similar capacity, usage, and audience. Our family tree visualization is similar to sixdegreesoffrancisbacon.com (Christopher Warren, et. al., 2018) in that we are organizing information using nodes, with each node also containing biographic information about the subject.

3.

Data

Since the launch of AfricanCalifornios.org as a website in 2022, we have added several data sets allowing for more accurate results. Initially we combined information from the California Census of 1790 with about 1,000 entries with the much larger ECPP database with several hundred thousand entries. While the ECPP has a large data set, its entries critically lack racial identities since most records merely designate individuals as either indigenous or non-indigenous. Only by combining the information from other sources, such as the 1790 census, and aggregating them into a larger database can a clear understanding of the African presence be made manifest. Since then we have added the census of San Jose (1783), and three censuses from Los Angeles (1781, 1783, and 1821). These censuses were carried out by the Spanish government, which essentially at this point was just the military, and contains a little over a thousand names of the first settler-colonists to California. Critically, these censuses contain the perceived race of the individuals as identified by the Spanish census taker. However they are only a small portion of the population, recorded during a few discrete years.

Table 1. Major genealogical data sources for this project.

| Data Sets |

Dates |

Entries |

Racial data? |

Source |

| ECPP - Baptism |

1768-1850 |

104,000 |

No |

ECPP (2022) |

| ECPP - Marriages |

1768-1851 |

28,000 |

No |

ECPP |

| ECPP-Burials |

1768-1852 |

71,00 |

No |

ECPP |

| 1790 Census |

1790 |

1009 |

Yes |

Mason, Census of 1790 |

| Census of San Jose |

1783 |

66 |

Yes |

AGI, Guadalajara 267 |

| Census of Los Angeles |

1781 |

55 |

Yes |

Mason, Los Angeles |

| Census of Los Angeles |

1785 |

43 |

Yes |

Mason, Los Angeles |

| Census of Los Angeles |

1781 |

300 |

Yes |

Mason, Los Angeles |

4.

Methodology

The first step in analyzing this data is aggregating it. Google Colab cloud computing platform was used for all programming. The ECPP is split into three sets of records: baptisms, marriages, and death. Each set of records contains information regarding the individual in question, as well as some auxiliary information about that person. A

Person data structure was created in code in order to store all of this information regardless of which record it originated from, so, as each record is read in, a new Person data structure is created with a unique id and added to our dataset. Part of the information regarding this person is their parents and children, so as these new people are encountered a new Person data structure is created and linked to that of the previous. Processing the ECPP in this manner is fairly simple as each person has the mission in which they were baptized, as well as their baptismal number.

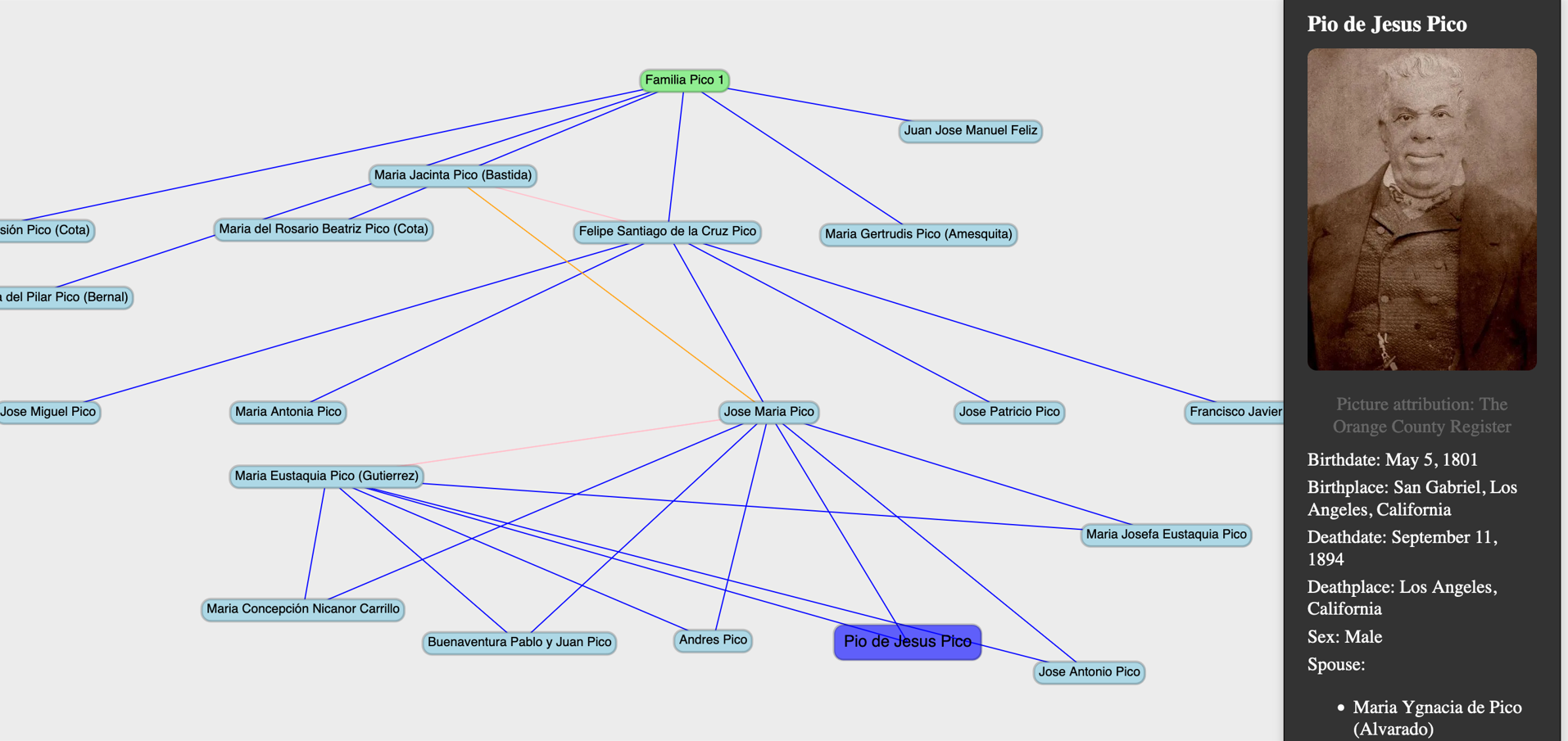

Figure 2. Sample family tree visualization with insert on AfricanCalifornios.org.

Figure 2. Sample family tree visualization with insert on AfricanCalifornios.org.

However, this is not the case when joining the ECPP with the 1790 California Census. Doing this required the creation of a matching algorithm that assigns each census person to their ECPP counterpart with various levels of tolerance for imperfect matches. This algorithm uses a fuzzy string matching Python library called “TheFuzz”, to determine if two strings are the same with slight misspellings. Once this data is joined the next step is to traverse through a person's parents and propagate the race indicator of that person and their descendants to their children.

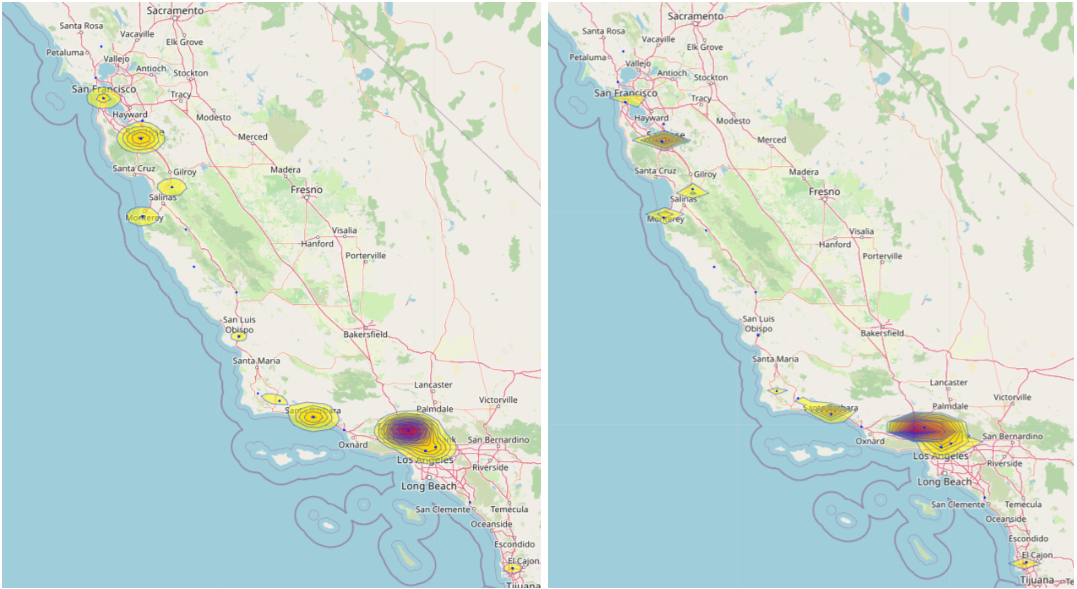

Figure 3. Heat map of African Californio presence based on strict (left) and permissive (right) criteria.

5.

Results

Based on an analysis of census and sacramental church records, we normalize names and identify distinct individuals and family trees. Of those we identify three generations of individuals whom we determine to be of African descent, based on a fairly strict and a more permissive criteria which we postulate would be close to an estimate for the upper and lower bounds of the population. In addition, we conduct a geographical analysis of all census and birth/death/marriage records filed at California missions.

Figure 2. Sample family tree visualization with insert on AfricanCalifornios.org.

Figure 2. Sample family tree visualization with insert on AfricanCalifornios.org.