1.

Introduction

As an interdisciplinary research field that applies digital approaches to problems from different fields of the humanities, the Digital Humanities (DH) produce a variety of heterogeneous research outputs (Pempe 2012). This phenomenon can also be seen within the sub-discipline called Computational Literary Studies (CLS), an evolving field of research combining traditional literary scholarship with methods and technologies from Computer Sciences and Computational Linguistics.

As can be expected, CLS research finds expression in traditional publications such as journal articles, conference papers etc. that describe scientific findings and results. However, the corpora on which such research is often based - often created during research processes themselves - also belong to the outputs of this field of studies. In addition, research projects in the CLS frequently develop non-paper research outputs (NPRO) e.g., annotation guidelines, models, and tools. Furthermore, comprehensive datasets, visualizations and presentation layers can count as results of CLS research (e.g. Helling et al. 2021).

All these NPROs are a result of scholarly work and by way of being reused by other researchers they can have a high impact in their respective field. From a research data management (RDM) perspective, they are to be made findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable in the sense of the FAIR-Principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016), so as to foster scientific progress (Bryant et al. 2017). In fact, research foundations like the European Union

1

, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF)

2

in Germany and the German Research Foundation (DFG)

3

(DFG 2021, 2022), but also research institutions such as universities more and more require researchers to plan and implement research data management strategies.

4

In doing so, they encourage sustainable and collaborative research across national and cultural borders.

Some approaches for fostering the visibility of these NPROs already exist: (1) the German Research Foundation (DFG) has published a new CV template

5

to be used when applying for a project funding. This template includes fields for non-canonical publication forms such as software. (2) There are initiatives discussing metrics on data publications (e.g. Make Data Count

6

or the Charité Dashboard on Responsible Research

7

). (3) Within the Digital Humanities, alternative publication formats (e.g., data papers or papers with code

8

) have spread to closely connect peer-reviewed texts with research data or executable code described in the texts themselves. Nevertheless this focus is on the connection of a NPRO to a paper publication, which can be problematic if no reference publication exists, or the set of authors of the NPRO does not equal that of the paper (Henny-Krahmer / Jettka 2022).

9

In addition, platforms for articles on NPROs often focus on a specific type of NPRO (data, software, digital edition).

10

Infrastructure initiatives can start from providing visibility to resources

11

and the general need to find new forms of dealing with NPROs is discussed (Maryl et al 2023), however more superficially than specifically.

A much more fundamental problem is that funding and research institutions rarely recognize NPROs in the advertisement of academic positions and in the evaluation of academic careers.

With this paper, we want to discuss this fundamental contradiction, which can be summarized as follows: on the one hand research results besides peer reviewed paper publications constitute central scholarly contributions in the DH and they are expected to be made findable and accessible. On the other hand the scholarly system often provides neither funding nor credit for the publication of such non-paper research outputs. Using the example of the Computational Literary Studies we argue for acknowledging NPROs as a valid addition to one’s list of scholarly contributions. It is our opinion that all stakeholders – researchers, funding institutions, research institutions – would benefit from such a change in awareness.

2.

The heterogeneity of scientific results exemplified by the Computational Literary Studies

Since 2020, the German Research Foundation (DFG) has funded a priority program for the Computational Literary Studies, SPP 2207.

12

During the first funding period (2020-2023), ten different projects were part of the program. In April 2023 the second funding period started (2023-2026) with eight projects. In addition, in both cases a central project was responsible for the research data management within the priority program. During the first funding period, the central project conducted a qualitative and quantitative survey on RDM aspects in the CLS (Helling et al. 2022a) and developed RDM strategies and infrastructural services (Helling et al. 2022b) for the SPP 2207. Furthermore, it curated a comprehensive list of the heterogeneous achievements

13

of the projects. This list features not only traditional article and paper publications, but also annotation guidelines, tools and platforms, datasets and analyses as well as conference papers, workshops and other activities resulting from the projects in question.

14

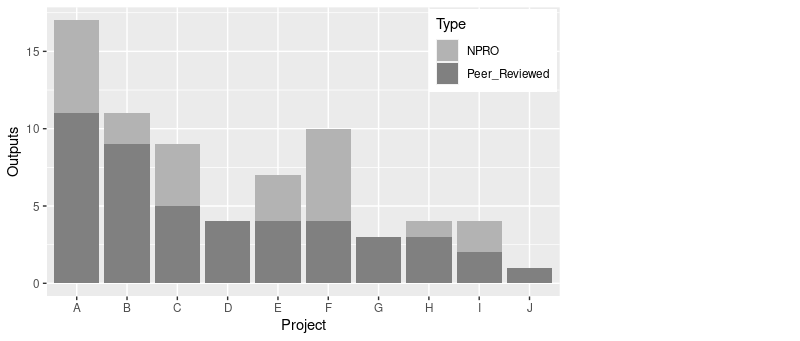

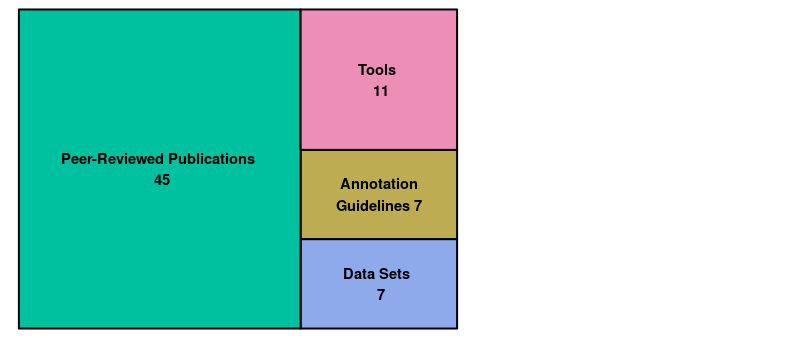

Noteworthily at least eight out of ten projects in the program’s first funding period would benefit from the inclusion of NPROs in their publication lists (see Fig. 1). Although the number of article and paper publications is higher, there is also a significant number of NPROs (see Fig. 2).

All these outputs and publications are relevant in the context of their projects. Due to the fact that there are no domain specific infrastructures for publishing and archiving this variety of publications, most of them are stored on generic repositories. Nevertheless, all outputs and publications of one project need to be connected to each other, because together they form the comprehensive result of the project. This is realized through Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) and in the context of the aforementioned list of achievements.

15

3.

NPROs and Peer Review

We are aware that realizing any approach to improve the acknowledgement of NPROs would mean overcoming several obstacles. Publications need to be peer reviewed to be considered as valuable scholarship. This implies a need to define criteria to evaluate the quality of the publication types we have referred to in this paper. Clearly, such criteria and the peer review process would have to be defined by domain experts, which some might consider too big a hurdle.

On the other hand, is it likely for peer reviewed articles and papers to describe exactly those non-canonical publications such as datasets and the other outputs we have mentioned. If the articles and papers describing them are considered of good scholarly quality, probably, but not necessarily, connected NPROs would be similarly evaluated too. What should be evaluated with regard to those resources is their compliance to the FAIR-Principles in a domain-specific fashion (Helling et al. 2022b).

4.

Possible Solutions

The ideal solution to solve this discrepancy would be a peer review system for NPROs. That would require an extensive infrastructure and significant time investment on behalf of the potential reviewers, but initial steps toward a better acknowledgement of alternative research outputs are theoretically possible at a comparatively low cost, by applying the FAIR principles as a first criterion for evaluation. Though certainly providing no quality control for the actual content or research, application of the FAIR principles can at least ensure the possibility of quality control by fellow researchers. Using such a criterion would not necessarily require expert domain knowledge on behalf of the reviewer. In fact, it could be even realized by using tools for evaluating the FAIRness of digital objects and publications.

16

Defining a minimum FAIRness score as a threshold value for NPROs to be acknowledged with peer reviewed articles and papers could encourage a responsible resource management in the Digital Humanities.

This could indeed provoke a paradigm shift in science and foster a handling of NPROs in a quality-driven and (self-)critical way by both researchers as research data producers and research data users. After all, quality control can only be realized through community driven approaches and these can only be implemented if NPROs are made findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.

Moreover, a listing of citations of each NPRO could be another way of indicating impact. For instance, a tool or data set could be listed with the number of peer-reviewed research articles citing it to showcase its impact as a contribution to the research field.

5.

Conclusion

If all NPROs were to be listed and if they were acknowledged by research funders and scientific institutions, impact on the research field would be more comprehensively represented in a publication list. Moreover, this could have the potential for fostering the management of research data and outputs in the sense of the FAIR-Principles. The possibility of adding NPROs to publication lists could motivate scholars to raise the quality of these kinds of outputs and potentially foster the (self-)critical handling of these resources. However, quality assurance for and the acknowledgement of NPROs has to be developed and established by scientific communities, for ensuring an acknowledgement by funders and scientific institutions.

In our talk, we will describe more in detail our vision of fostering the acknowledgement of NPROs. In addition, we will transfer this vision to different research fields within the Digital Humanities. By doing so, we will argue for the need of a paradigm shift within the scientific community for acknowledging NPROs as relevant publications.

Notes

1.

https://erc.europa.eu/apply-grant/starting-grant [23.05.2024].

2.

https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/en/home/ [23.05.2024].

3.

https://www.dfg.de/en/index.jsp [23.05.2024].

4.

e.g., https://data.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/rdm-policy/; https://rdm.univie.ac.at/rdm-policy-and-faq/; https://www.openscience.uzh.ch/en/definition/policy.html [23.05.2024].

5.

https://www.dfg.de/formulare/53_200_elan/ [23.05.2024].

6.

https://makedatacount.org/ [23.05.2024].

7.

https://quest-dashboard.charite.de [23.05.2024].

8.

e.g. https://jcls.io/articles/; http://www.zfdg.de/sonderband/5; https://openhumanitiesdata.metajnl.com/articles; http://www.lrec-conf.org/ [23.05.2024].

9.

Smith et al. (2016) e.g. describe in their software citation principles that a paper can be cited in addition to the software itself.

10.

https://data.post45.org, https://culturalanalytics.org/, https://joss.theoj.org, https://openresearchsoftware.metajnl.com/, https://ride.i-d-e.de/ [23.05.2024].

11.

https://www.dariah.eu/, https://clsinfra.io/, https://text-plus.org/ [23.05.2024].

12.

https://dfg-spp-cls.github.io/ [23.05.2024].

13.

Accessible as classical publication list (https://dfg-spp-cls.github.io/achievements.html [23.05.2024]) and Zotero library sorted e.g. by item type (https://www.zotero.org/groups/4667571/spp-cls-achievements/library [23.05.2024]).

14.

Other examples for the collection of more than article and paper publications: https://netherlands.openaire.eu/; https://www.zotero.org/groups/4533881/textplus/library [23.05.2024].

15.

We have to stress that the list of achievements is by no means complete. It only summarizes all publications that were reported by the projects of the SPP 2207 to the central project.

16.

https://www.thehyve.nl/articles/evaluation-fair-data-assessment-tools [23.05.2024].