1 While the subfields of the Digital Humanities (DH) that focus on computational text analysis have grown rapidly over the past fifteen years in the sophistication of their methods, the same is not true of the material on which this analysis can be performed. While dataset publication and citation has increasingly become a standard in the sciences 2 , scholars in the digital humanities working on text, especially in-copyright text, face significant barriers to dataset publication and, subsequently, data sharing 3 . Whether under the rubric of Cultural Analytics, Computational Literary Studies, Stylometry, Distant Reading or Text Mining, the gains in these subfields have largely been methodological (Jänicke et al., 2015; Underwood, 2019; Gius and Jacke, 2022). The large-scale resources that have enabled work in these fields, particularly for Anglophone texts, are the same that existed over a decade ago 4 . The challenges of assembling relevant corpora for particular projects have been relegated to the bibliographical, archival, and, for in-copyright works, legal domains, which have long been subordinated to the methodological concerns of the field (Birkholz et al., 2023; Bode, 2020). And while these challenges are slowly (if unevenly) being addressed, the gap between developments in methods versus in corpora may still be widening.

In the United States, the recent introduction of the Text and Data Mining (TDM) exemption to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) has been promoted as a central step towards overcoming the legal dimension of these challenges 5 . The new provision decriminalizes the act of extracting text protected by Digital Rights Management (DRM) software in the US so that scholars can build responsible corpora for research. Yet the particulars of this exemption leave many of the same legal hurdles in place, particularly for scholars working independently or at smaller institutions without access to significant research budgets and institutional resources. In order to work within the boundaries set by the exemption, scholars face new restraints around sourcing, processing, storing, and sharing these materials, many of which contradict the norms of the field. Similarly, the easing of legal barriers does not address the other kinds of challenges practitioners in DH face when sourcing texts (Ketzan et al., 2023).

Our goal for this paper is to document our attempt to take advantage of this new legal framework to build a bespoke corpus of largely in-copyright, born-digital texts for the purpose of text mining. Starting not from a found corpus of pre-assembled works, but instead from a list of desired texts around a single subject (in our case, literary theory), we sought to collect a complete corpus of 402 twentieth-century publications, following all the rules set by the TDM exemption. In the end, we have discovered that even when supported by both a large, wealthy university library and a grant specifically funding the assembly of such a corpus, building a born-digital corpus remains difficult, if not impossible. Our struggles implicate not just the legal mechanisms of copyright, but also the publishing and bookselling industries, the collection and purchasing protocols of university libraries, and the general availability of texts themselves. Indeed, we have found the acquisition of texts under these constraints to be slow, painful, and expensive.

Our underlying project, for which the corpus we discuss in this talk is assembled, leverages text-mining methods to examine the movement of ideas, concepts, and discourses between a corpus of literary theory and one of literary criticism. The first corpus we therefore required is a hand-curated corpus of literary theoretical texts—the focus of this paper and detailed below—and a collection of literary critical monographs. We defined “theoretical texts” as those that primarily focus on the philosophic, linguistic, or sociological mechanisms of the theory rather than its immediate application to literary works. We juxtaposed these selected texts with a much larger and less focused critical corpus based on the recently recovered scans of books taken by the Google Books initiative from Stanford's library. With both corpora in hand, we were able to compare them, using the hand-curated theory corpus to capture the linguistic and conceptual signatures of our chosen theoretical movements that could then be mapped to individual works in our corpus of criticism.

To assemble the theory corpus, we carefully selected a few dozen works, mostly monographs, from eight theoretical fields—feminism, Black studies, Marxism, psychoanalysis, post-structuralism, postcolonial studies, narratology and Russian formalism. These fields, we felt, had a variety of different relationships to literary criticism that would facilitate comparative analyses in our later research.

As a preliminary step towards the compilation of our corpus, we checked if our library provides access to the text in question in an electronic form, including Google’s digitization initiative, and the details of that availability (namely whether the ebook was purchased by the library vs. subscribed, where only the former is permissible under the exemption). We prioritized obtaining born-digital versions of our texts wherever it was possible to do so, both because—in principle—this offers a considerable saving of time and labor, and because we wanted to acquire the cleanest possible texts with the fewest errors introduced via either scanning or processing (with optical character recognition [OCR]) the texts.

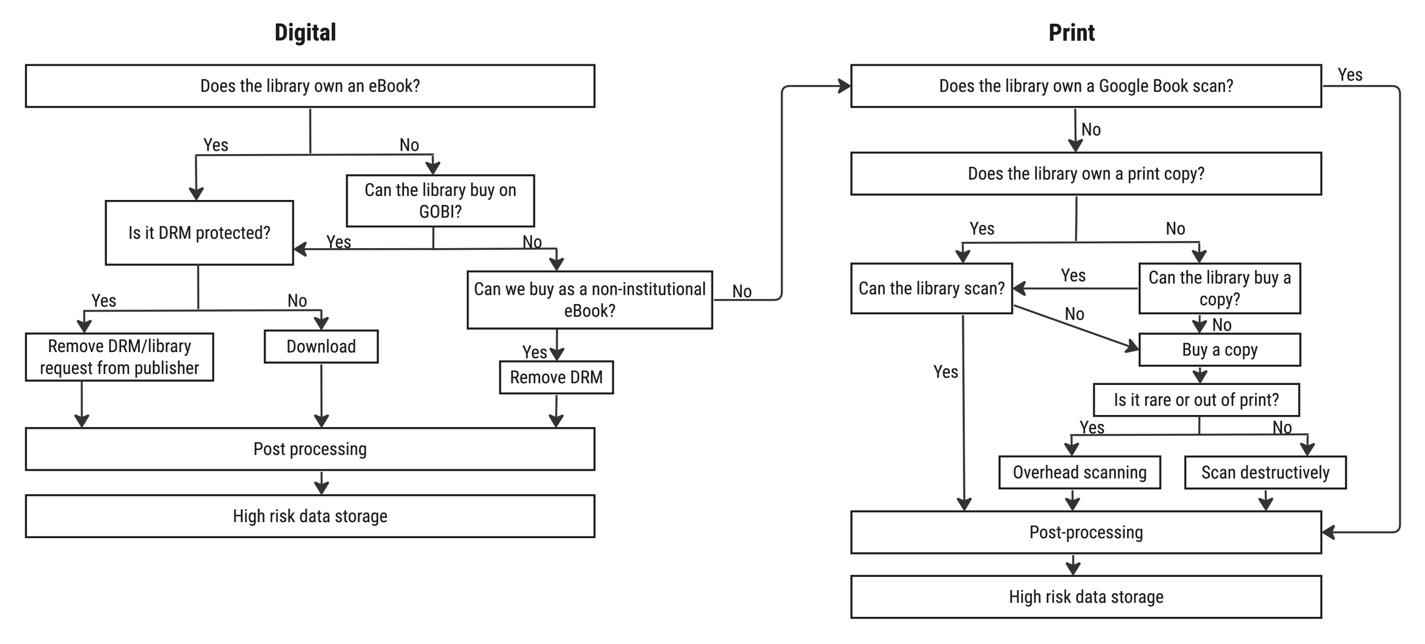

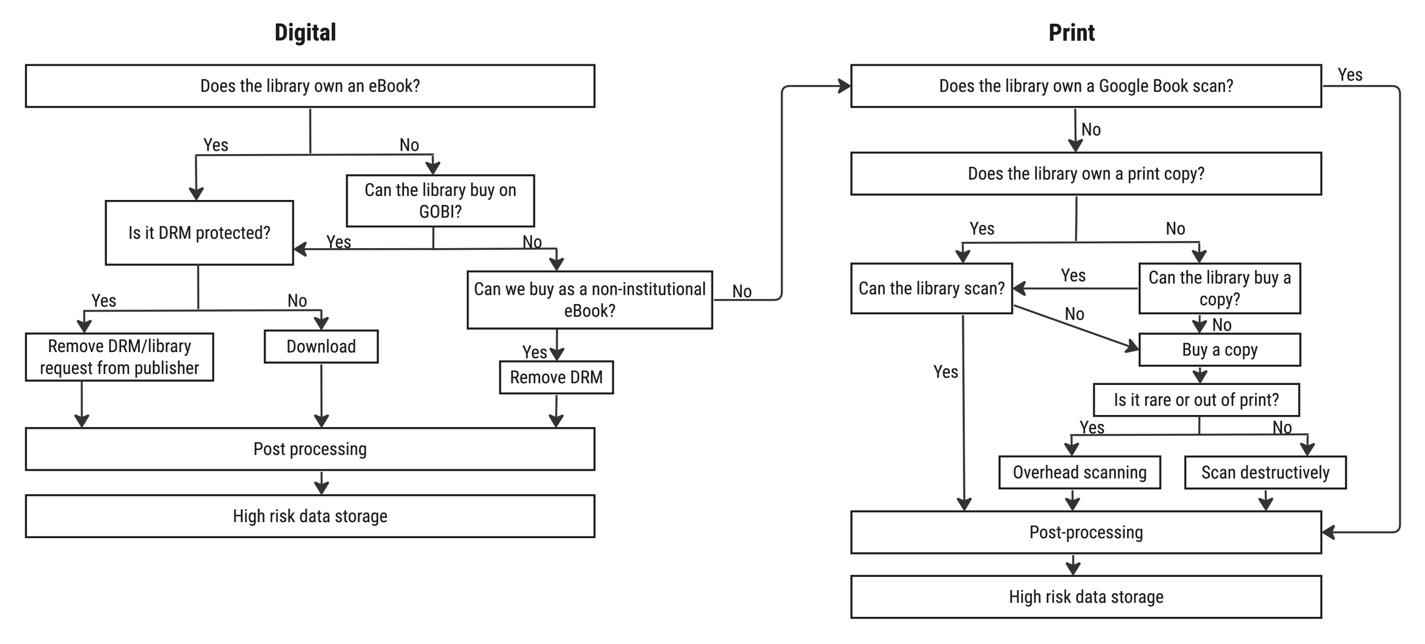

Initially, we conceptualized our acquisition of texts quite simply. We proposed to turn first to library-owned ebooks; then purchase ebooks as needed to fill in any remaining holes in the corpus; leaving, we naively assumed, a small residuum of texts to be scanned by the library or project members. Our work quickly grew vastly more complicated. We found, first, that the library owned electronic copies of fewer texts than we expected—even of widely read and cited texts—and the availability of existing ebooks changes relatively frequently. When requesting ebook purchases through the library, we were also confronted by spotty availability. When we turned to digitization, we discovered that not all the texts which Stanford had provided to Google as part of the Google Books initiative had actually been scanned. Even with printed texts, there were unforeseen complexities, and as our scanning queue grew, we ultimately divided it into two different workflows. The result, as shown in Figure 1, was a far more tangled, burdensome, and slow process than we had anticipated.

Figure 1: Final workflow for text acquisition

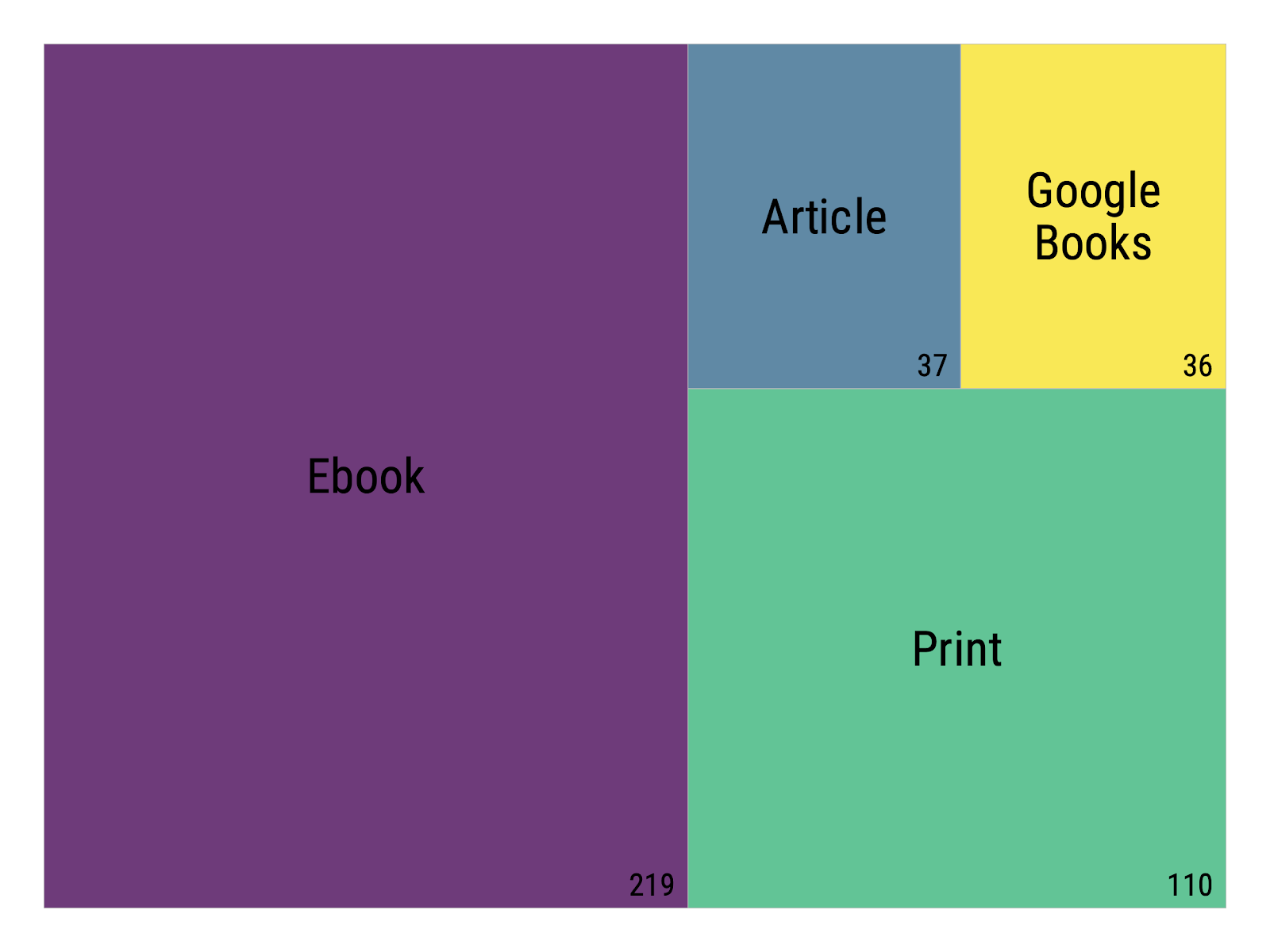

After eight months of work, we located a source for each of our 402 texts. Of these, 219—somewhat more than half—were born-digital files derived from ebooks, nearly exclusively “circulating” texts owned or perpetually licensed to Stanford University Libraries (see Figure 2). A small number of additional ebooks were purchased on non-institutional licenses. While born-digital sources, taken collectively, provide cleaner texts than digitized ones, they are encumbered by awkward workflows to remove DRM and extract text. Moreover, the need to track license information requires access to data that may not always be available to library users, and which is in any event likely unfamiliar to most scholars working outside of libraries. We found, then, that although ebooks presented a certain measure of labor savings and offered the highest text quality, they were more complicated to work with than digitized sources.

Figure 2: Overall corpus source types

Overall, while the bibliographic and material conditions have improved such that it is now possible to obtain a bespoke, hand-assembled corpus of selected Anglophone literary works in digitized format, possible does not indicate easy. From a bibliographic standpoint, we found the necessity of consulting, comparing, and tracking the availability of texts across multiple digital venues and platforms (open-access, library ebooks, digitized texts from already extant collections, etc.) brought significant administrative overhead. This required the expertise and access permissions of a librarian, which may not be available to all research teams and is beyond the reach of individual researchers not affiliated with a library. Without the well-resourced and cooperative library, we do not believe this project could have been completed within a reasonable timeline. While the recent changes to the DMCA have improved the legal situation for researchers wishing to work with copyrighted texts, the restrictions imposed by the DMCA exemption have made working under its terms particularly challenging. Projects considering this route would be well-advised to consider whether sufficient numbers of institutionally-owned, DRM-protected ebooks exist to justify the additional labor required to work with this category of text.

While it is tempting to look at developments like the DMCA exemption, the recent push by universities to create open-access archives of scholarship, and the ever-increasing size of repositories such as HathiTrust, and speculate that we are on the cusp of a revolution in sourcing an exponentially larger number of texts for our work, we are all too aware that such claims echo the utopian predictions of a decade ago (e.g., Poole, 2013). As much as things have changed (including the appetite of large language models for ever more terabytes of text), our research still takes place against a system that is structurally hostile to even the least responsible creation of bibliographically-based corpora.

This project is supported by a Public Knowledge grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

Borgman provides numerous examples of this in the sciences and social sciences, but is only able to point to the example of Archeology within the Humanities (Borgman, 2018)

Attempts to address the problems of data publication for professional metrics (tenure, funding and similar) have seen the recent development of hybrid models of dataset-article, such as Cultural Analytics ’s “Data Set” articles, Post45’s “data essays” or the Journal of Open Humanities Data ’s “Data Papers”.

such as Eighteenth Century Collections Online (2014) and Project Gutenberg (n.d.) (Guldi, 2021) (Perseus Digital Library, n.d.) (Burns et. al., 2009). Large bibliographical efforts at the national scale have created important new resources for a number of particularly European languages (Gallica n.d.) (Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, n.d.). Yet, despite these efforts, given the under resourced nature of non-English archives, the challenges we describe in this paper are just as pressing, if slightly altered, for other languages.

Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies. 37 CFR Part 201. For a research-oriented summary, see that of Authors Alliance (2021).