1.

Introduction

Place names (toponyms) have been widely used to refer to places, from people's daily communications to official documents over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales. A place name connects the textual and the geographic representation of a place or a region of interest. Here, the textual representation includes variations or alternative names, and the geographic representation consists of a representative point or a polygonal boundary. In addition, both representations should have temporal dimensions for historical big data research [1].

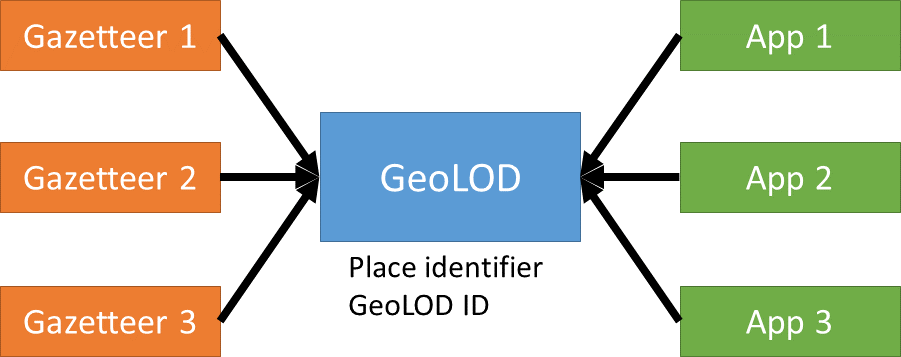

GeoLOD [2] is a platform to manage both representations of a place and serve as the hub of information about place names [3]. The key functionality is to assign a place identifier, GeoLOD ID, for each entry in a gazetteer. Both textual and geographic representations of a place are stored as metadata of the place identifier. Those metadata can be retrieved through the API, thus allowing other apps to share the place identifier for various purposes. In the following, we discuss how GeoLOD connects gazetteers and apps for historical big data research, as shown in Figure 1.

Historical place names are an essential resource for historical research [4, 5]. For example, the World Historical Gazetteer collects names of historical places worldwide. However, our motivation to build a new platform, the GeoLOD, is two-fold: (1) the platform should have Japanese language-specific features, and (2) the platform should improve data quality progressively based on stakeholder feedback. Here, the definition of a place name is loose because each gazetteer was built on a different definition. In future work, we plan to define a semantic relationship between place names to unify the variety of definitions.

2.

Japanese Historical Gazetteer

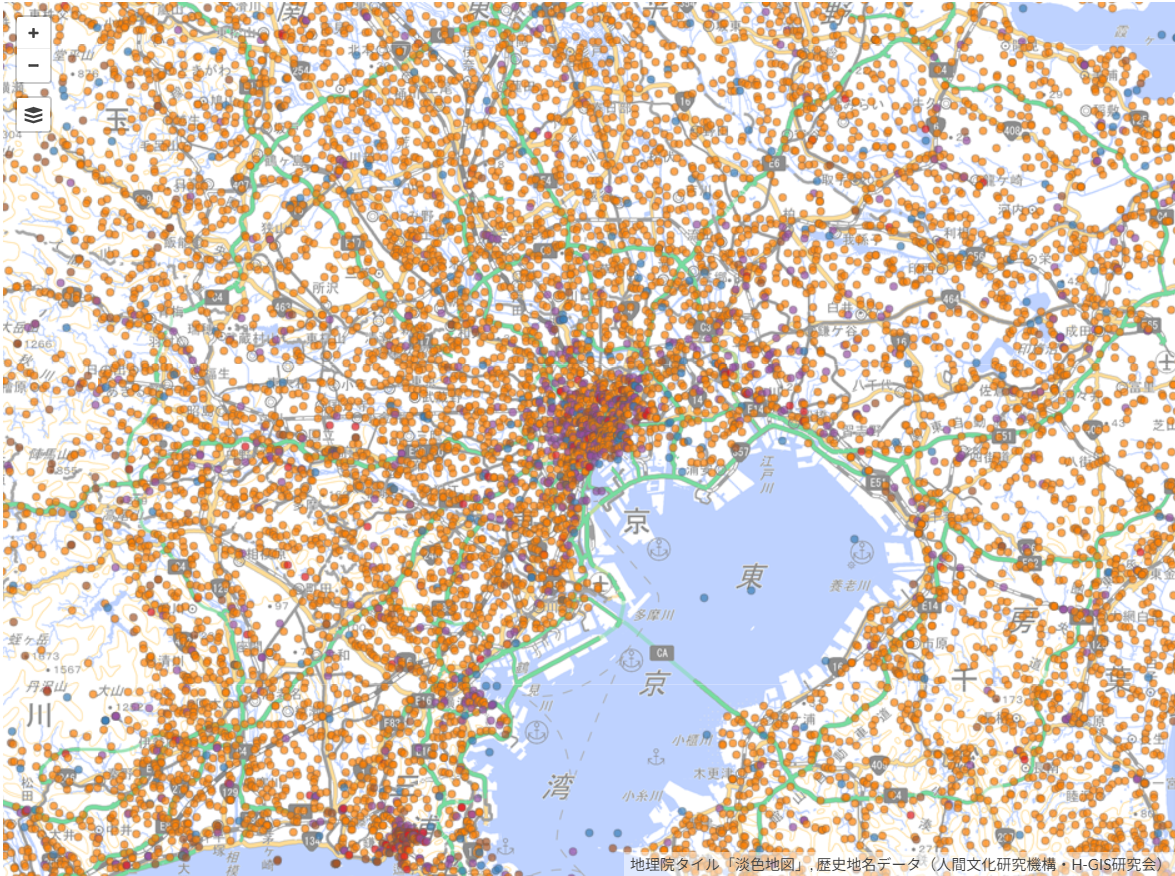

First, we introduce the Historical Place Name Data [6], published by the National Institute for the Humanities and the H-GIS Research Group. This is one of the largest machine-readable Japanese historical place names datasets, with 298,914 entries. Most of the place names were collected from old maps published in the Meiji and Taisho eras (about 100 years ago), and the coordinates of place names are determined by the location of labels on the map, as shown in Figure 2 [7].

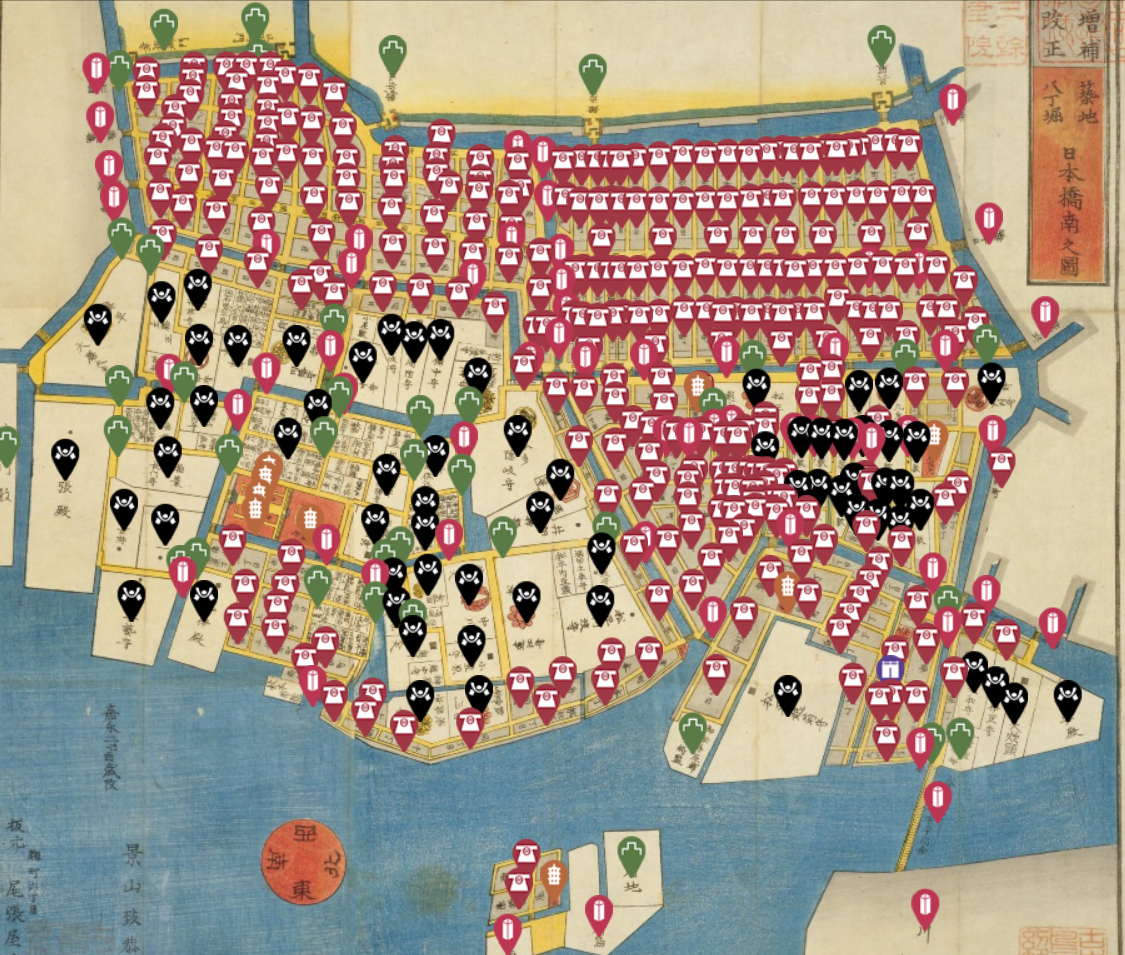

Second, we developed Edo Maps [8], the collection of about 9000 place names in Edo, a city later renamed Tokyo, as shown in Figure 3. Those place names were collected from 29 sheets of old maps published around 1850, and the place names were transcribed from the maps with coordinates on the old maps. Coordinates were later converted to latitude and longitude through georeferencing using the Map Warper web service [9]. This dataset is valuable for studying the urban environments of the historical city of Edo.

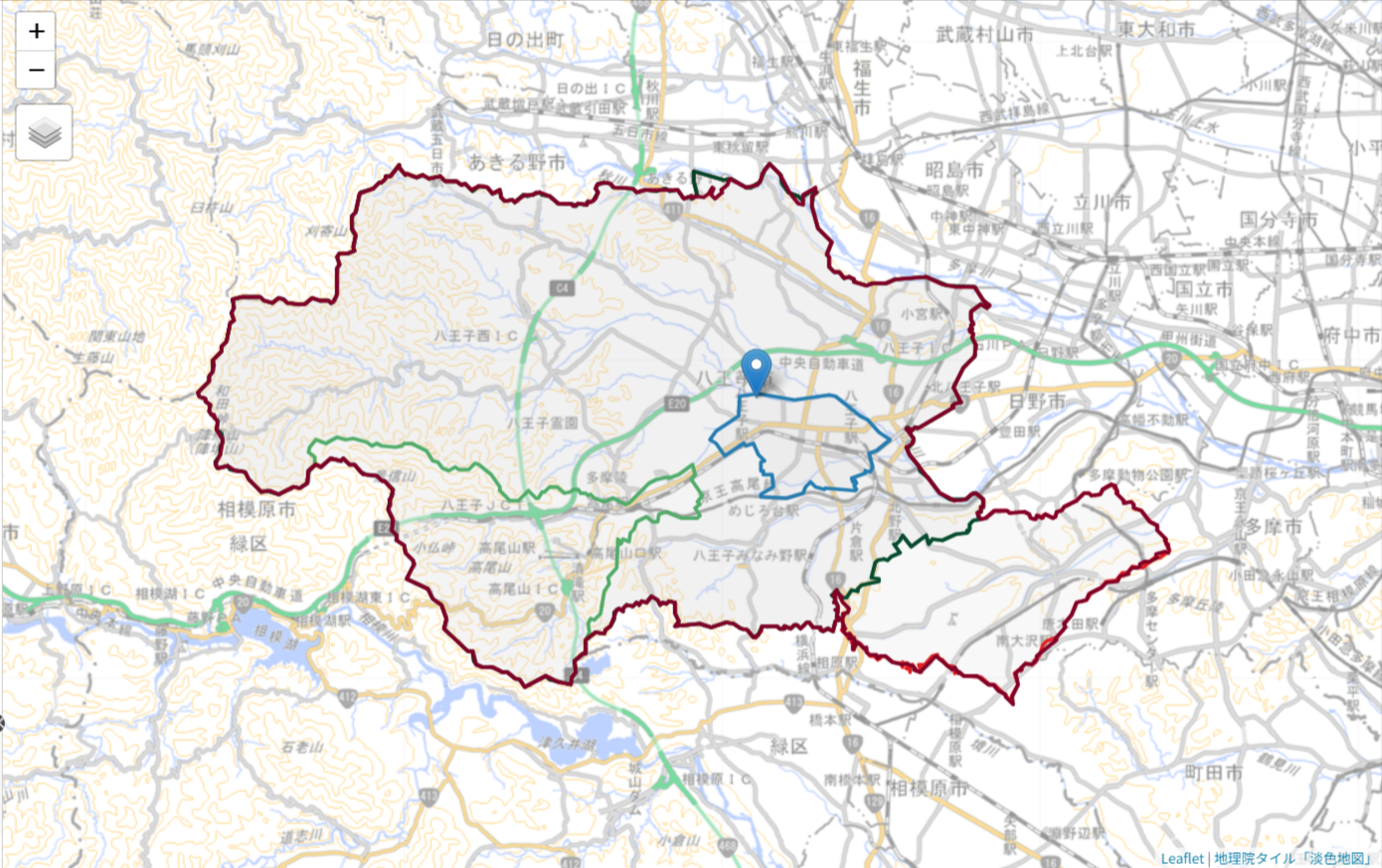

Third, we developed the Historical Administrative Boundary Dataset [10], integrating several open datasets from the Japanese government to establish identifiers for Japanese cities and towns after the current administrative system started in 1889. We have already released a complete dataset after 1920 to visualize the temporal boundary change over time, as shown in Figure 4. This dataset is valuable for studying modern Japan after the Meiji Era.

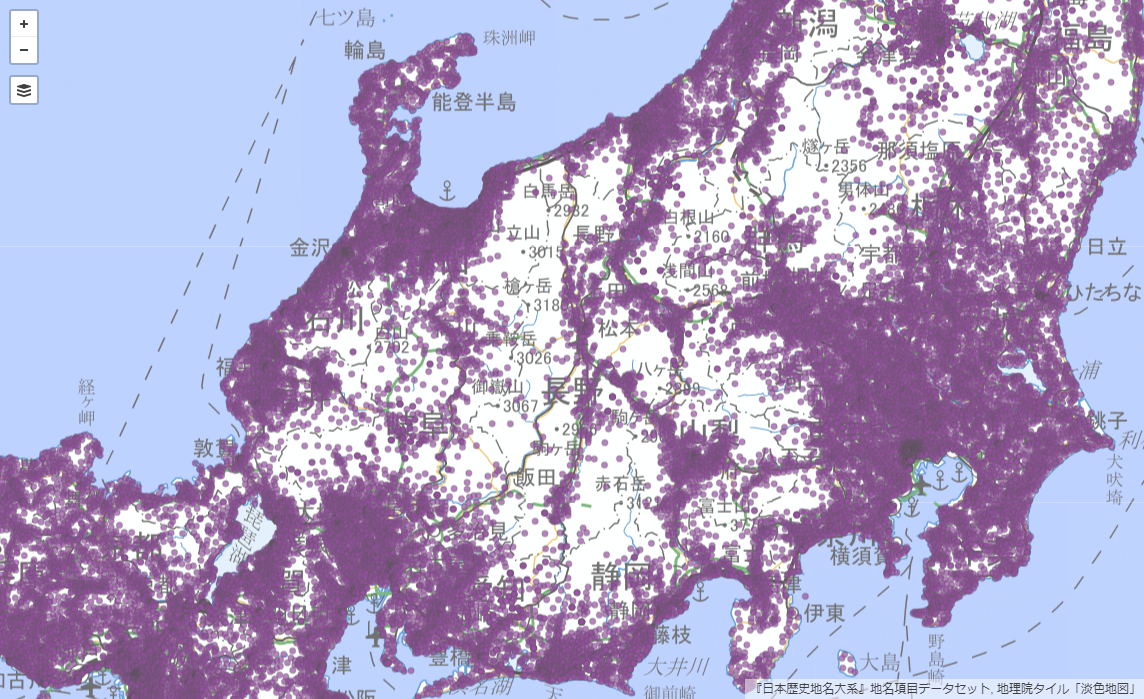

However, this dataset has a missing part: cities and towns in the Edo period. To create an open gazetteer for the missing part, we must collaborate with a publisher that maintains authoritative resources, such as paper encyclopedias or subscription services. Thus, we started a collaboration with Heibonsha. They published Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei (Japanese Historical Placename Encyclopedia), one of Japan's most authoritative gazetteers, with more than 150,000 entries in 50 volumes, published for 25 years (1979-2004), supported by hundreds of academic and community historians throughout Japan. We agreed with the publisher to release about 80,000 IDs and place names of this encyclopedia as open data with the CC BY license [11]. Furthermore, we added value to this dataset with the latitude and longitude of place names, which were not included in the original encyclopedia. We developed a workflow to estimate the location using jageocoder [12], a flexible Python-based Japanese address geocoder developed by our collaborator. The final dataset can be visualized as Figure 5.

The dataset's release had a huge impact on scholars and citizens. This was also surprising for a publisher because only a part of the encyclopedia published long ago was released as open data. This result suggests that publishers' content has the potential to regain attention to their academic assets, transform them for the digital age, and contribute to society in new ways.

3.

Historical Big Data Apps

We uploaded all the gazetteers introduced above to GeoLOD so that GeoLOD can assign an identifier to each place name. Then, we use GeoLOD to link a mention of a place name in a document to a GeoLOD ID so that we can analyze historical documents in a geographic context. To help this entity linking task, GeoLOD provides an API for searching place names and returns GeoJSON data about the place. This is an example of historical big data research, which integrates machine-readable data created from multiple sources and applies data-driven algorithms developed for big data research today.

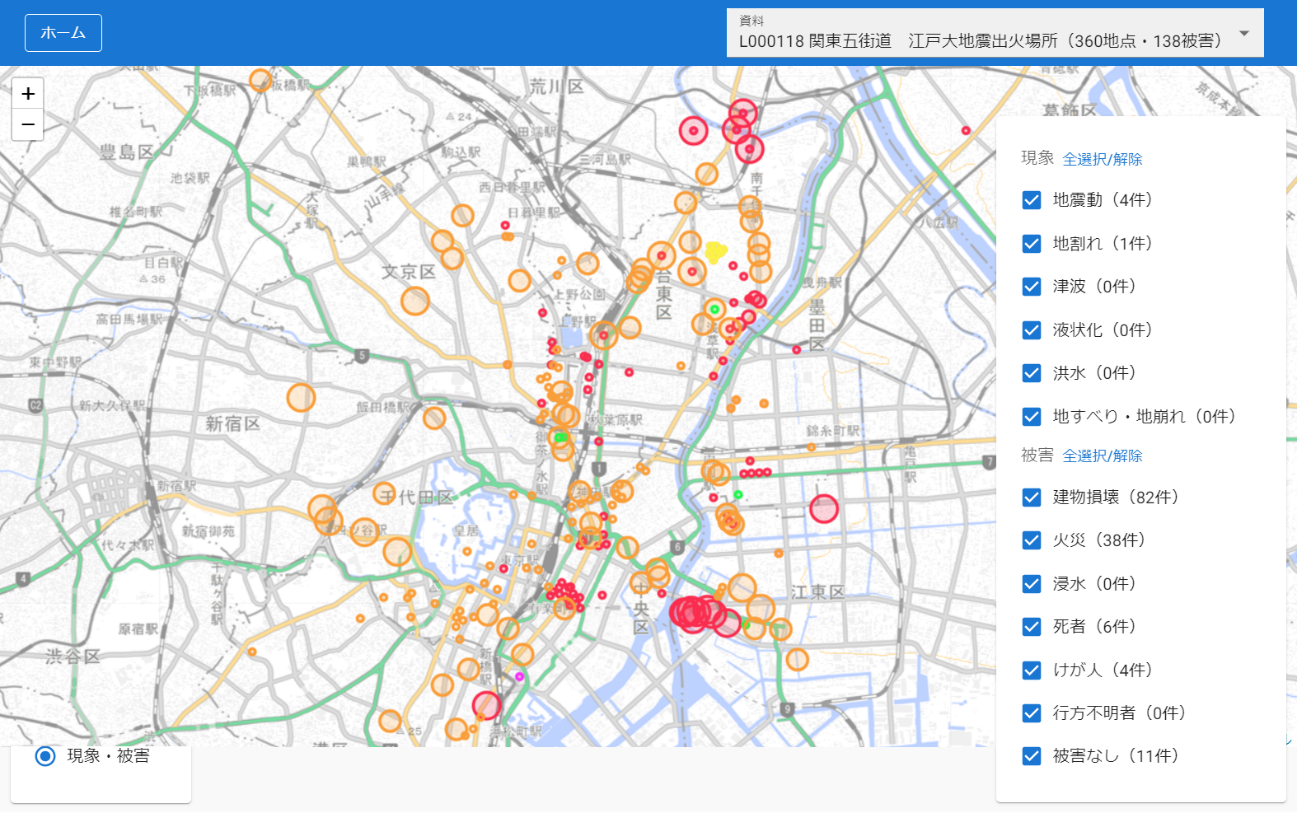

"Minna de chushaku" (let's annotate together) [13] is an app that uses the GeoLOD API. It has an interface for annotating entities, such as place, time, and event in plain text. Figure 6 shows a current project for annotating historical documents recording the Ansei Edo Earthquake in 1855 that caused extensive damage to Edo. Using GeoLOD API to assign the GeoLOD ID to historical documents, we can visualize the geographic distribution of earthquake damage using metadata for each GeoLOD ID. We also annotate historical records called "Tempo Gocho" (the list of towns and rice crop production in the Tempo Era in the Edo period) to annotate towns in the transcribed text. Those results will help us position historical documents in the past world and use machine-readable data and modern technologies for the quantitative analysis of the past.

4.

Future Plan

From the Edo period to the present, we plan to collect more Japanese historical gazetteers from open data created by scholars and citizens and negotiate with publishers to release some of their assets as open data. We also increase the diversity of historical big data apps and collect feedback from users to improve the quality of the gazetteers.

Figure 1: GeoLOD connects Gazetteers and Apps using the place identifier, GeoLOD ID.

Figure 2: Map of Historical Place Names visualized around Tokyo.

Figure 3: Old maps of Edo with place names transcribed, classified, and visualized on the map.

Figure 4: Historical Administrative Boundary Dataset and the temporal change of the boundary of one city shown in different colors.

Figure 5: The visualization of Nihon Rekishi Chimei Taikei points around Central Japan.

Figure 6: Ansei Edo Earthquake and the geographic distribution of damage recorded in historical records.