1. Introduction

Among the well-educated literati in pre-modern Chinese society, poetry (shi 诗) has been celebrated as a literary genre of high status. However, during Qing Dynasty, a significant shift occurred as literati and scholars began to embrace long fictional narratives as a popular medium for more sophisticated storytelling. One distinctive feature of Qing vernacular fiction, partially influenced by this shift, is the integration of verse and prose, with poems frequently referenced and recited as part of the fiction works. The existing research has explored the role and narrative functions of embedded poems in storytelling, particularly focusing on their use in individual, canonical literary works such as The Dream of the Red Chamber (Xu 2008; Wei 1998; Zhao 2013; Rao 2023; Wang 1992; Saussy 1987; Hegel 1987). However, there is a noticeable gap in the literature regarding the exploration of embedded poems in a broader range of fiction, especially in lesser-known and non-canonical works.

In our work, we synthesized the insight from previous research but moved beyond it to investigate embedded poems as a literary phenomenon in Qing vernacular fiction from 1644 to 1911. More specifically, we explored the feasibility of analyzing poetry’s narrative functions with large-scale fiction data and computational methods. Our dataset contains 360 poems extracted from 18 Qing vernacular titles that are publicly accessible through the Chinese Text Project. Our main research question is: What narrative functions do embedded poems serve in Qing vernacular fiction? To address this question, we first applied computational methods leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) to detect and separate poems from prose in the fiction. In addition, we performed detailed content analysis to establish a framework to understand the roles and functions of embedded poems in vernacular fiction and tested the capacity of computational models to automatically detect and classify such narrative functions. Our findings contribute to the existing literature by delineating the variety of narrative functions of embedded poems with a larger, more comprehensive corpus of Qing fiction and new computational methods.

2. Preliminary Tests

2.1. Poem extraction test using ChatGPT

The extraction of embedded poems was accomplished with the help of ChatGPT-3.5. Since most of the Chinese verses are short, we first extracted several hundred passages with less than 20 characters, and extracted one sentence before and after each extracted passage. An initial examination showed that these texts contain not only poems but also Chinese couplets (duilian), chapter titles, or text with incorrectly formatted paragraph breaks. Then we presented ChatGPT this question in Chinese: "Analyze the text below to see if it contains poems, and if so, retell all the poems you find:", along with a couple of extracted paragraphs as examples. Although primarily trained on modern Chinese text from the internet, ChatGPT exhibited the ability to comprehend text written in vernacular and classical Chinese dating back to the Qing Dynasty, and to identify most of the poems embedded in these text passages. By analyzing the few identification errors, we found that the semantic cues such as "诗曰" (The poem says) and "有诗为证云" (There is a poem to prove it), and the formal elements of poems, typically comprising four or eight lines with five or seven characters in each line, are crucial to identify the poems. This result holds significant relevance for our future work analyzing larger numbers of poems, suggesting that we might not need to train a model for the task ourselves.

2.2. Classify narrative functions of embedded poems in Qing vernacular fiction

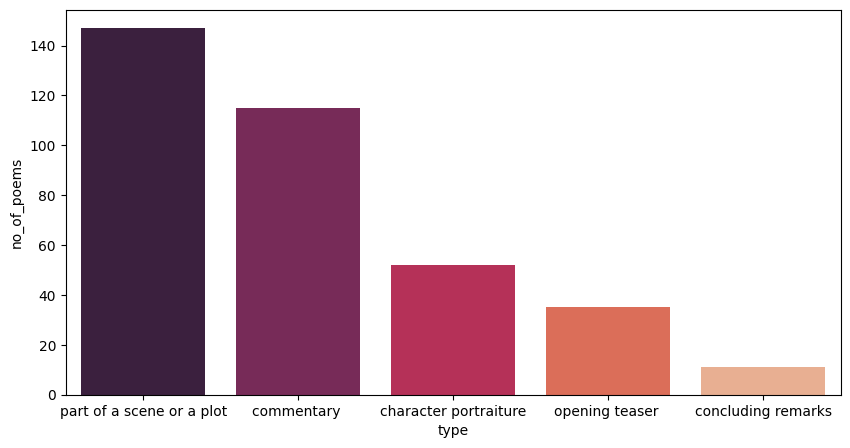

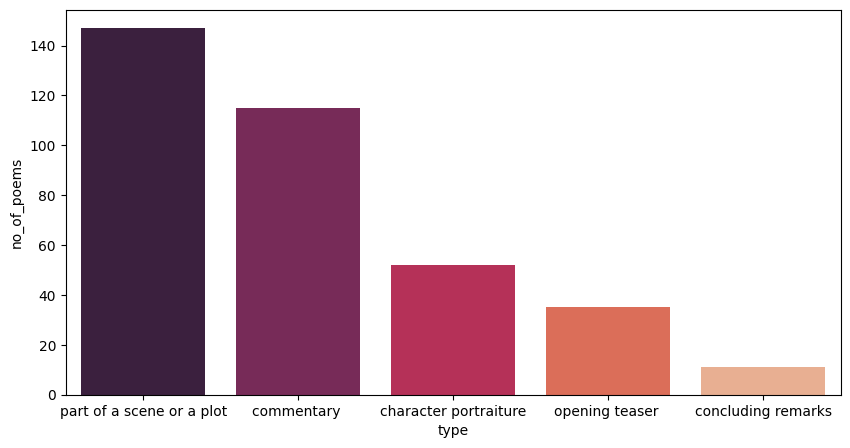

With an exploratory analysis of 360 poems and a synthesis of previous literature, we identified and annotated five narrative functions of the embedded poems: opening teaser, character portraiture, commentary, “part of a scene or a plot,” and concluding remarks. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the five functions across our annotated poems.

Figure 1. Distribution of the five identified narrative functions of embedded poems in Qing vernacular fiction.

We then attempted to automatically classify the poems based on their narrative functions. Since such a small amount of unbalanced data is insufficient for fine-tuning and evaluating existing pre-trained models, we tried Zero-Shot classification instead. The best result were obtained using an XLM-Roberta-based Model, yielding an accuracy of 0.38 and an F1-score of 0.20. ChatGPT achieved the same F1-score, but a lower accuracy ( Ba rbieri et al 2022) .

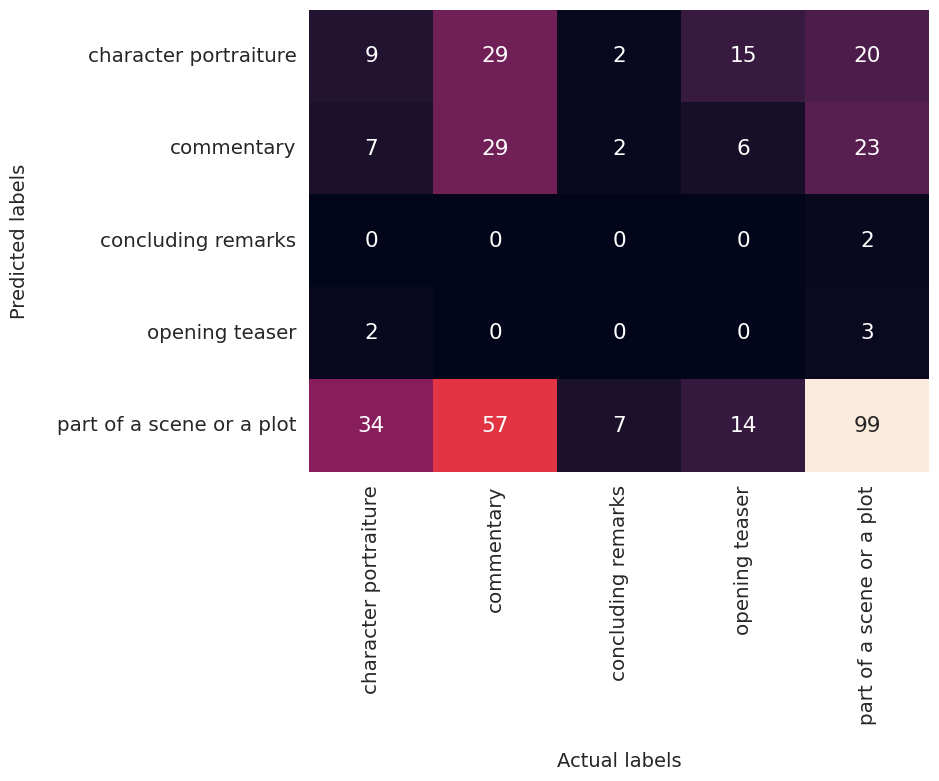

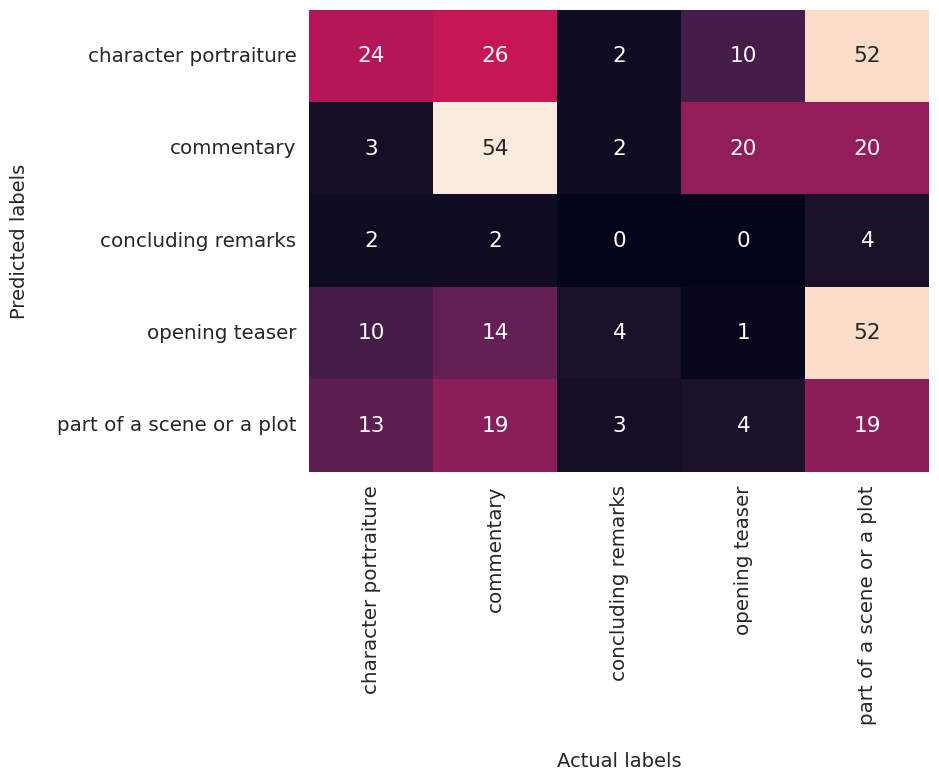

As shown in Figure 2, the XLM-Roberta-based model categorized almost 60% of the poems as "part of a scene or a plot”. This suggests that such poems may be more readily identifiable than others, although this was not confirmed in the tests using ChatGPT. Interestingly, ChatGPT demonstrated a better performance in classifying “commentary” and “character portraiture” poems (see Figure 3). The unsatisfactory classification result can be attributed to multiple reasons: Firstly, the models were trained on modern Chinese prose, but our poems are from the Qing dynasty, a very different time and style. Second, the subjective nature of interpretation may have influenced the labeled functions of some poems, as they were annotated manually by a single individual during this initial study phase. Thirdly, the narrative function of a poem often depends not just on the poem itself but also on its context, such as surrounding sentences. Therefore, classifying poems may not be enough to model and operationalize our research interests.

Figure 2. Confusion matrix for Zero-Shot classification using XLM-ROBERTA-BASE-XNLI-ZH

Figure 3. Confusion matrix for Zero-Shot classification using ChatGPT

3. Discussion and Future Work

Our study demonstrates the potential and the limitations of leveraging LLMs to analyze embedded poems in Qing vernacular fiction. Based on these insights, we aim to enhance our approach in several ways: Firstly, we will develop a larger, more diverse corpus to create a language model better suited for analyzing Qing vernacular fiction. Additionally, we will explore alternative approaches that consider the prose context of the poems and the sequence in which verse and prose alternates. We also intend to improve the accuracy of human annotation by involving more annotators, thereby examining the impact of interpretive subjectivity on annotations. Further, we will broaden our investigation of narrative functions, modeling the intertextuality of poetry in Ming-Qing vernaculars from various angles. This includes examining whether functions differ across styles of the vernaculars, how the use of poems affects the fiction's perceived canonicity, and assessing the contribution of poems to the meaning of the fiction as a whole.