4. Results

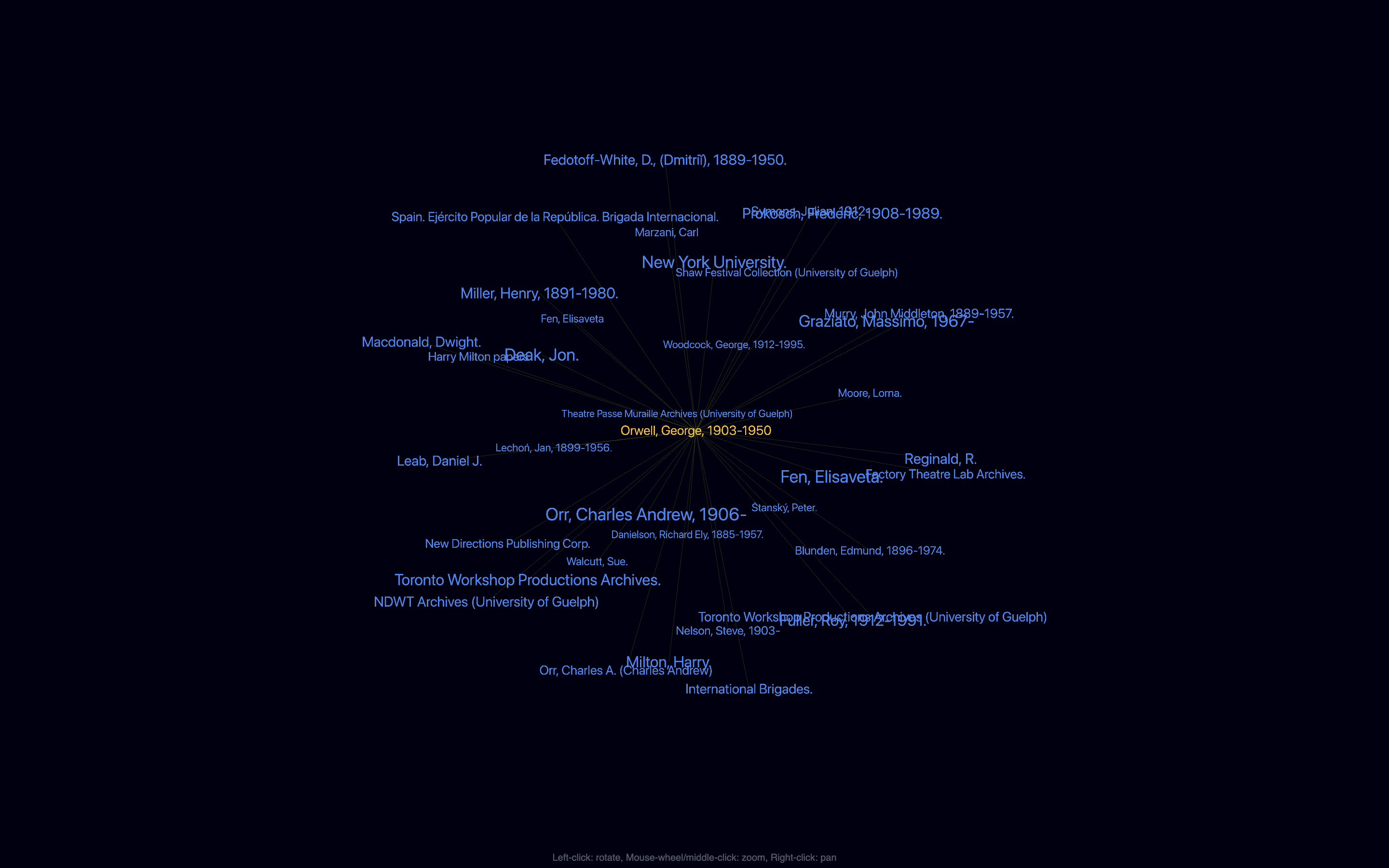

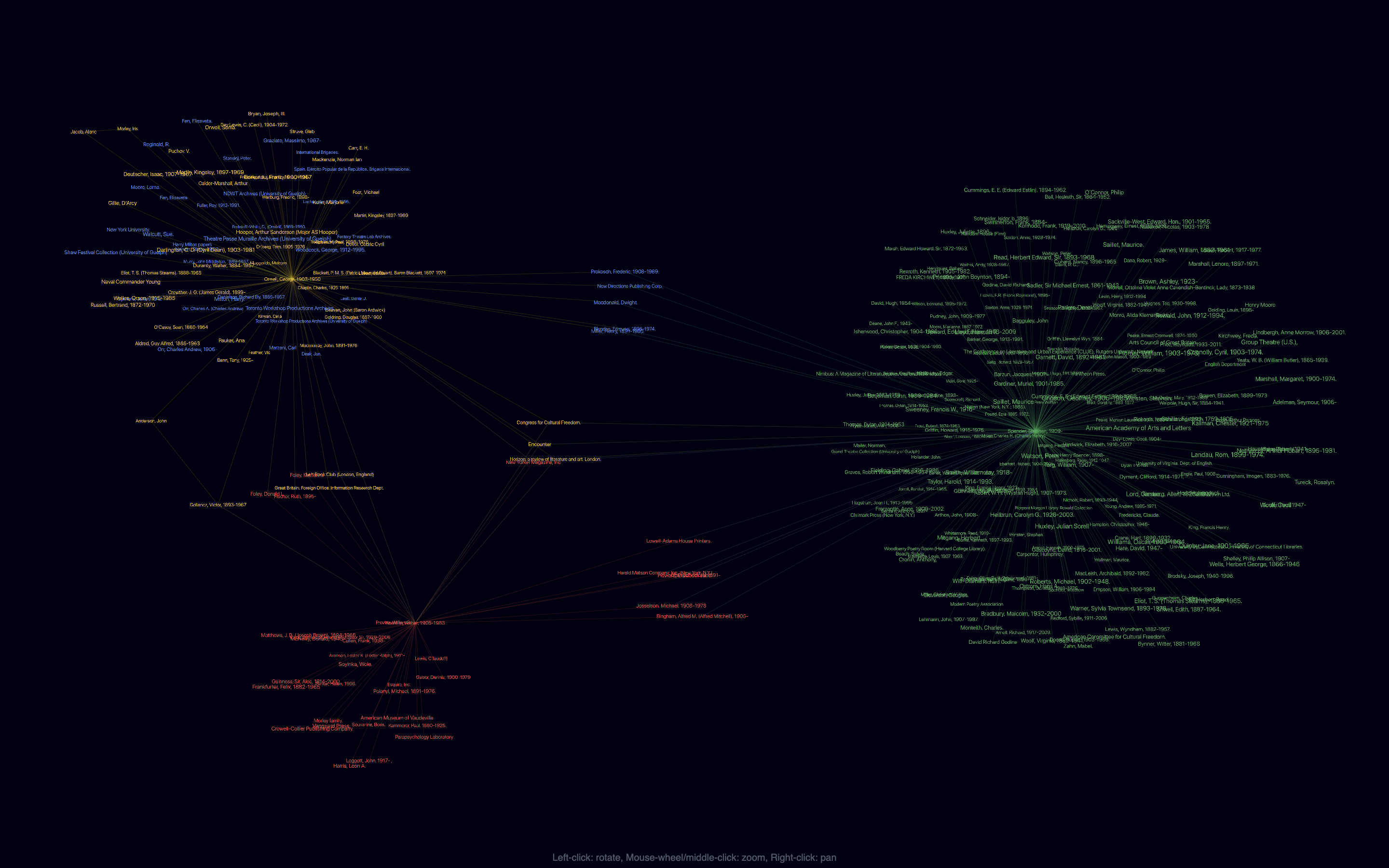

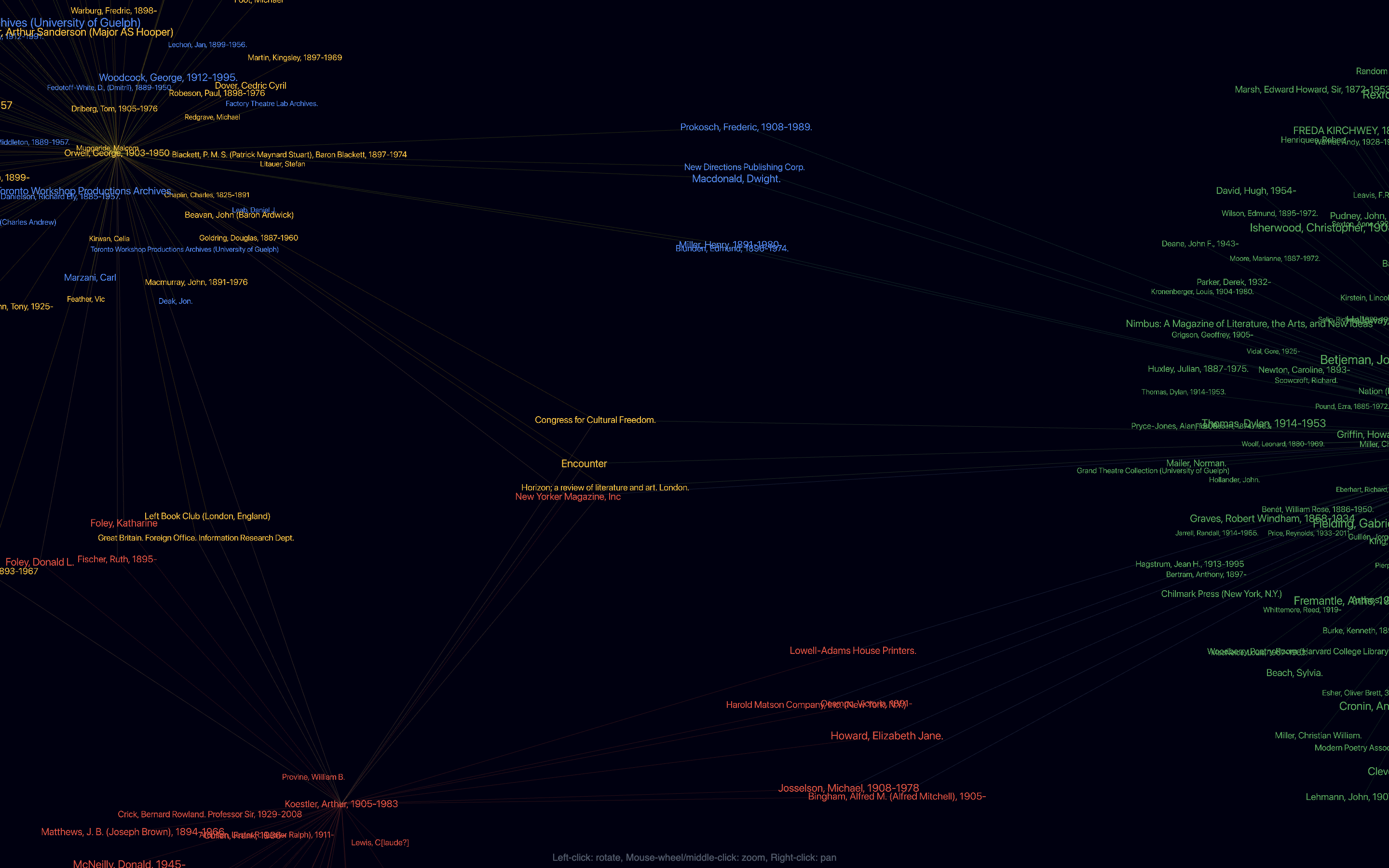

From the available SNAC data, we begin with a relation constellation consisting of 51 entities associated with Orwell (figure 1). We did not at this time look for further connections among the first-order connections. We then incorporate the named entities extracted from our declassified documents, adding a further 44 nodes and 45 edges for a graph of 96 nodes (figure 2). The associations we identify in our declassified test case archive nearly double Orwell’s first-degree relation constellation as mapped by the SNAC Cooperative. From here, we can begin to build out the graph by adding relation constellations for known entities. In this case, we include the SNAC relation constellations for two figures with known ties to the CIA activities, Stephen Spender, editor of the covertly funded literary magazine Encounter from 1953 to 1967, and Arthur Koestler, who consulted for both the IRD and the CIA on cultural matters (figure 3).

This triad begins to divulge instances of potential document or entity discovery that could be exploited by specialist researchers in literary studies or intelligence history. We note, for example (figure 4), the proximity of The New Yorker to entities with known or suspected links to covert state activities, the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CIA funded), Encounter (CIA funded), and Horizon (possible intelligence links). The location of a node within a particular set of constellations does not necessarily implicate the named entity in covert cultural diplomacy. It does, however, suggest an entity may be of interest as a previously unacknowledged recipient of state support or as an object with ideological sympathies to instruments of state influence.

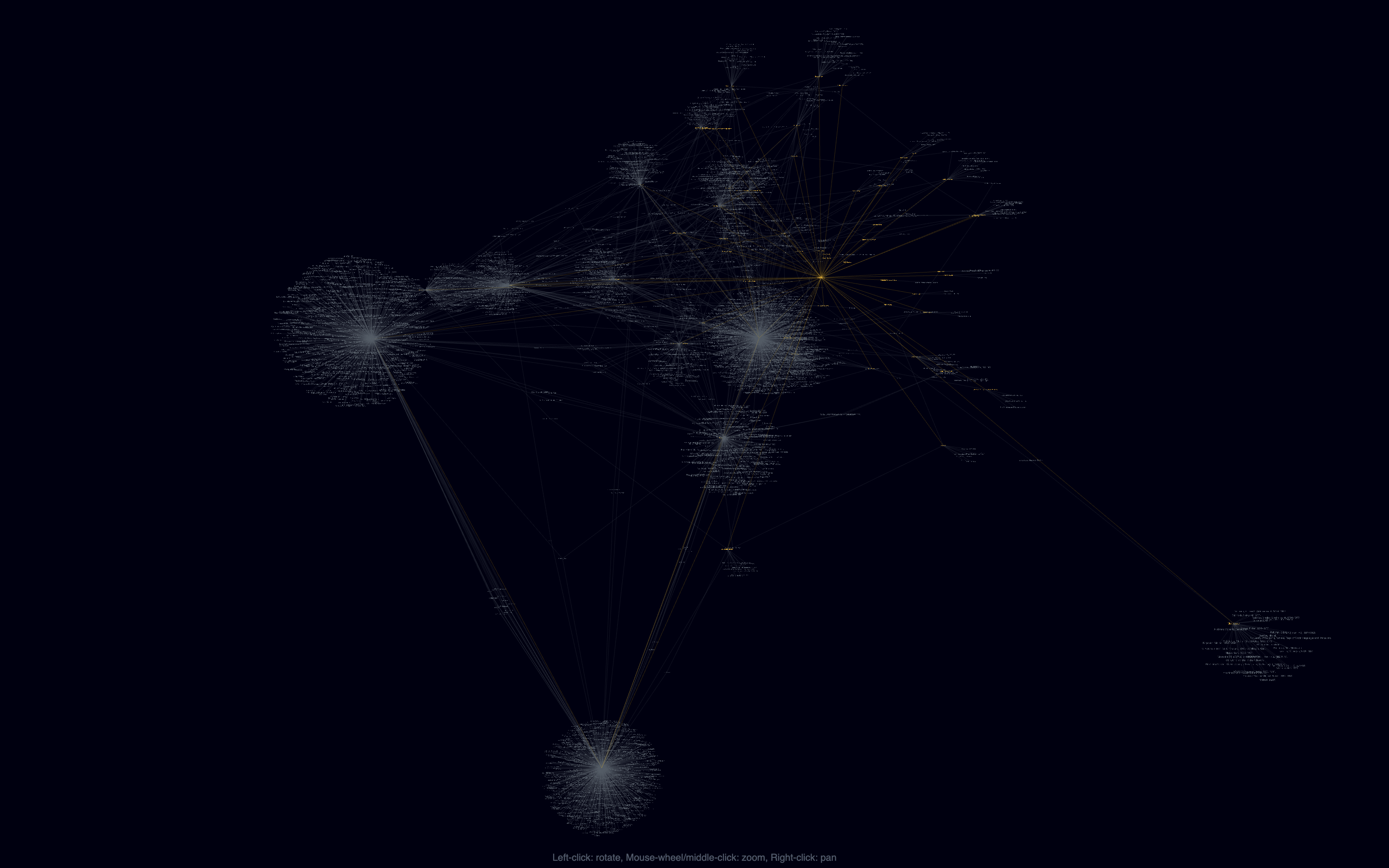

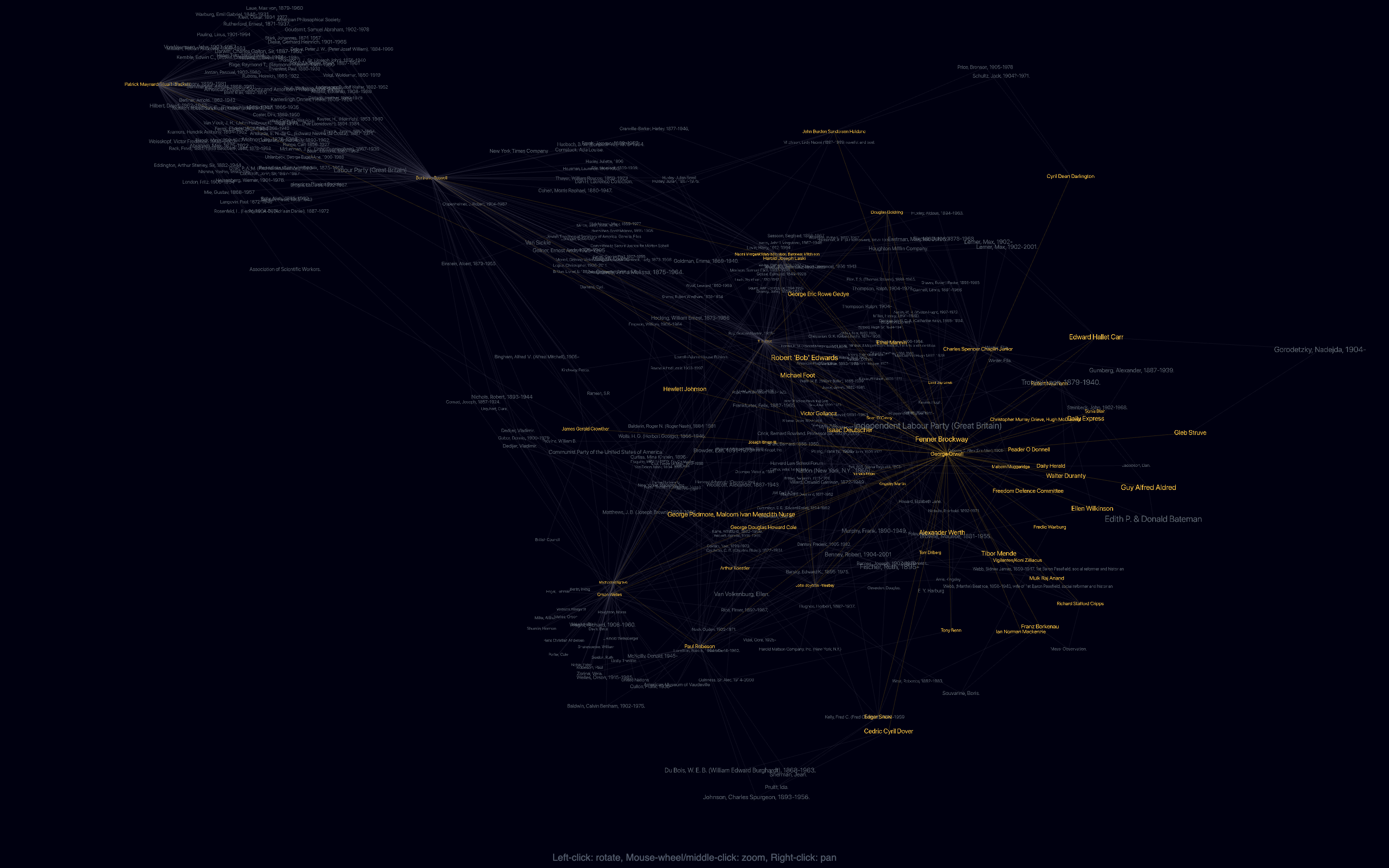

Finally, to demonstrate potential scalability for our broader project, we expand our case study network one more time by incorporating SNAC constellations for each neighbour node in the original graph of 96 nodes to produce a network of 3655 nodes and 4044 edges (figure 5). We filter the network to show only nodes with a degree or 2 or greater, resulting in a final graph of 347 nodes and 737 edges (figure 6). Fuller statistical analysis of this graph object is needed. Nevertheless, it points toward the generative potential in combining publicly available linked data with networks extracted from declassified documents to reveal large-scale patterns and relationships.

Figure 1. Screenshot of SNAC relation constellation (blue) for George Orwell (yellow)

Figure 2. Screenshot of SNAC relation constellation (blue) for George Orwell plus named entities extracted from declassified documents (yellow/red)

Figure 3. Screenshot of Orwell’s SNAC and covert relation constellation with two additional nodes: Stephen Spender (green) and Arthur Koestler (red)

Figure 4. Screenshot detail of Orwell’s SNAC and covert relation constellation with two additional nodes (Spender and Koestler) highlighting the location of The New Yorker magazine in the neighbourhood of three covert (or suspected) enterprises

Figure 5. Screenshot of Orwell’s SNAC and covert relation constellation expanded to include SNAC relation constellations for all named entities in the SNAC database

Figure 6. Screenshot of Orwell’s SNAC and covert relation constellation expanded to include SNAC relation constellations for all named entities in the SNAC database and filtered to show only entities degree 2 or greater