In today’s digital research landscape, the proliferation of proprietary vendors has resulted in silos or “walled gardens” of scholarly materials. These walled gardens are designed to keep scholars inside them. For instance, scholars can conduct computational analysis on HathiTrust materials within the walled garden of HathiTrust Research Center’s “Data Capsule,” or on works owned by Gale/Cengage within the walled garden of Gale’s “Digital Scholar Lab.” Though these platforms facilitate computational analysis, they limit scholars’ ability to compare across collections. What if scholars could analyze materials from more than one resource at once? What discoveries could scholars make if they weren’t limited by a particular vendor’s metadata, OCR quality, indexing practices, or built-in Natural Language Processing tools? 1

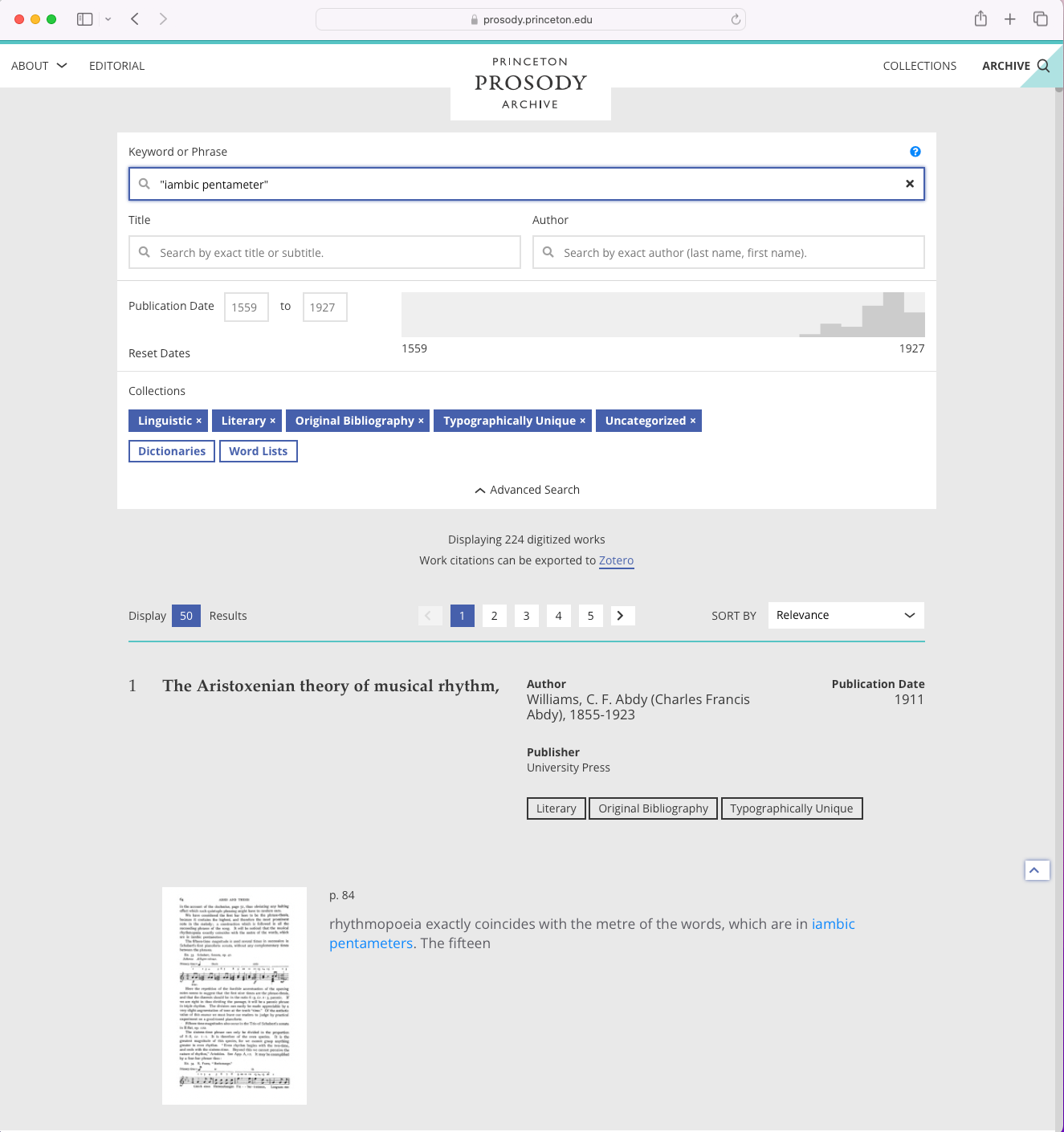

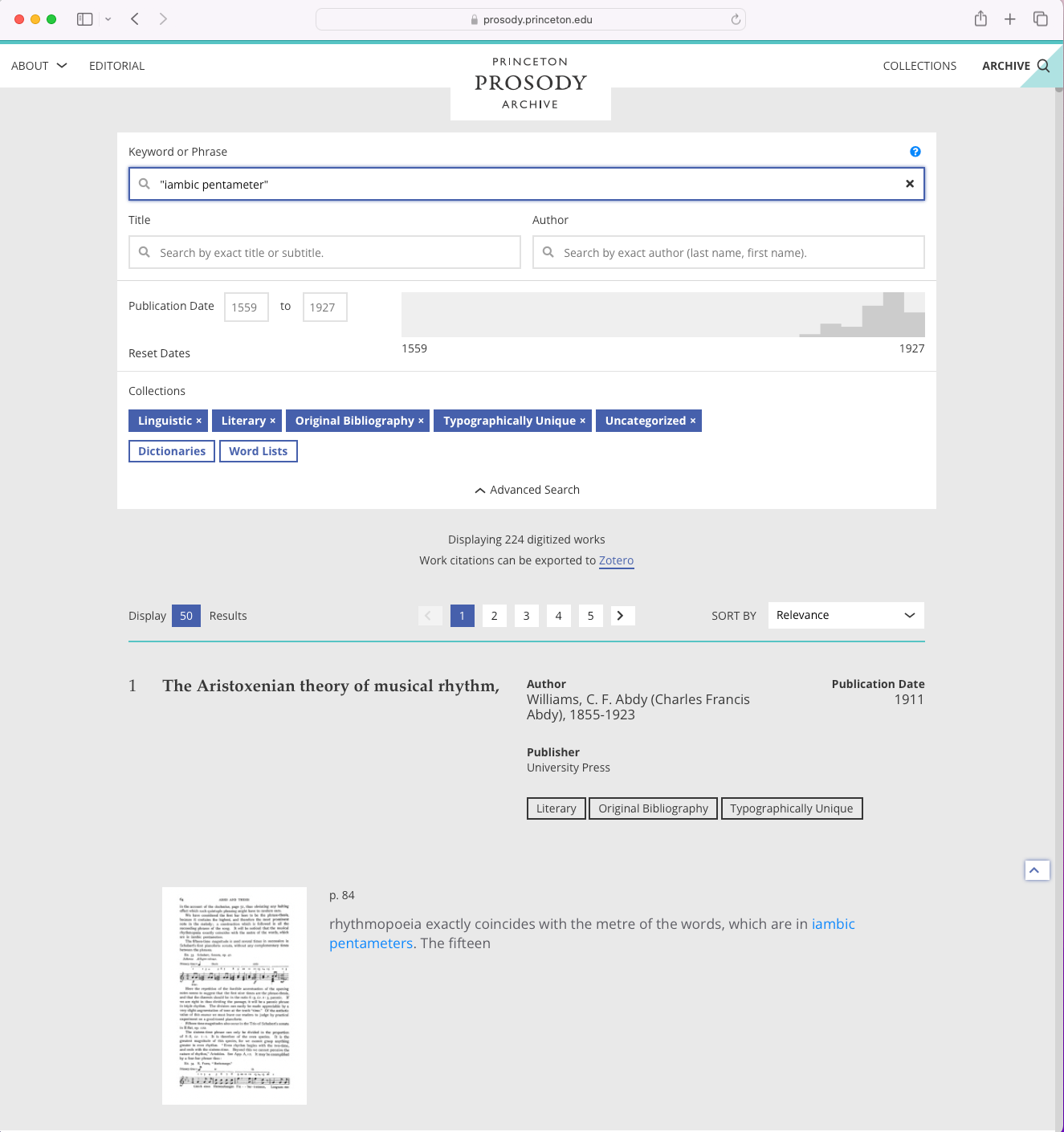

The Princeton Prosody Archive (PPA), an open-source, full-text searchable database of more than 6,000 English-language digitized works about the study of versification and pronunciation, is a rich case study showing how it is possible – but difficult – to break out of those walled gardens. By bringing together full-text OCR, page images, and bibliographic metadata from both HathiTrust Digital Library and Gale/Cengage’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) into one searchable interface (figure 1), the PPA is one of the first humanities resources of its kind to collect, curate, and analyze materials across disparate proprietary vendors. Ultimately bringing together a total of three separate resources, the final version of the PPA is the culmination of a sixteen-year process of negotiating with vendors, building the public-facing web application, and making the data usable.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the PPA search interface.

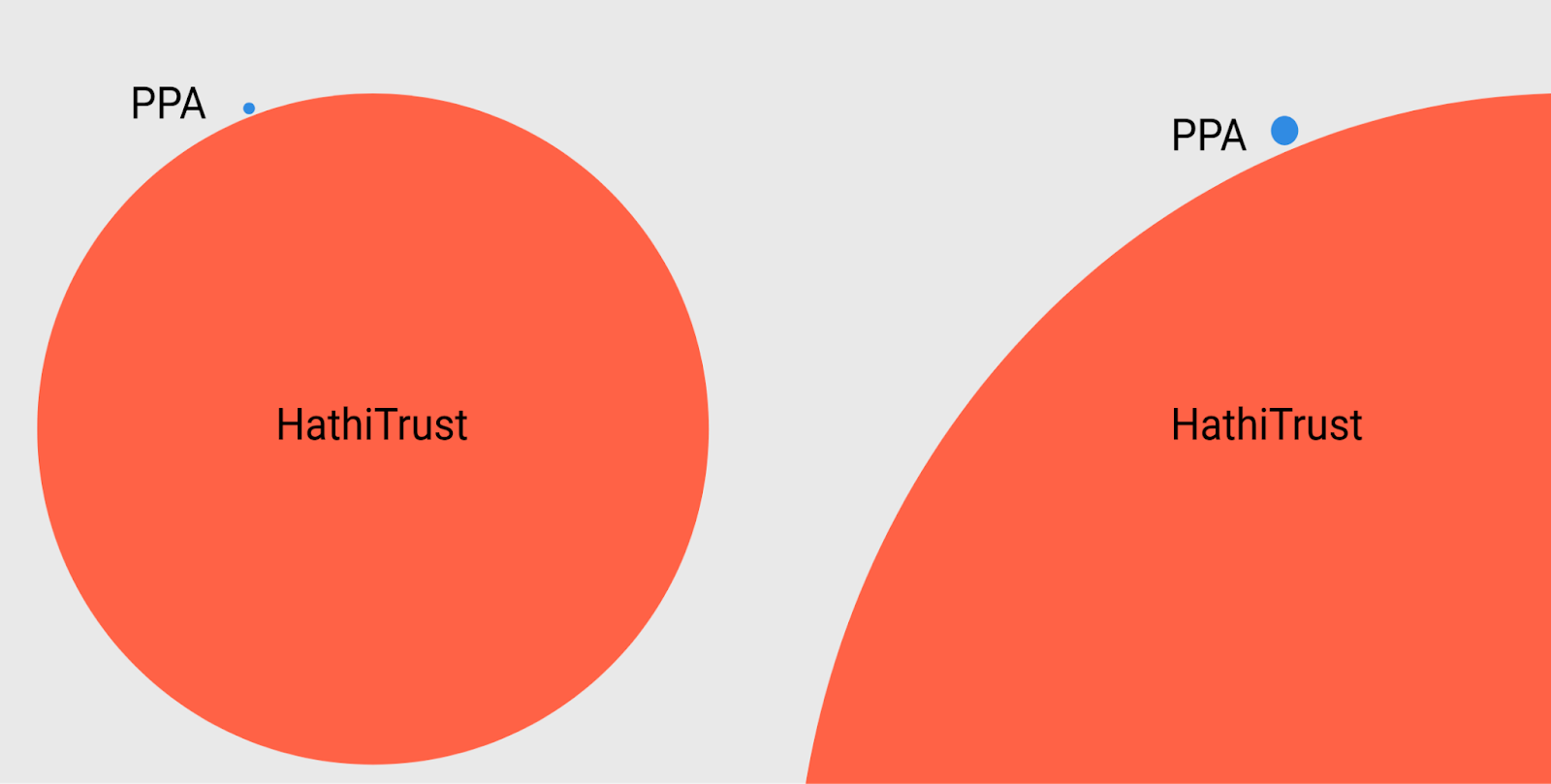

Our poster presentation will illuminate the roadblocks we faced along the way to developing this innovative digital research infrastructure. The difficulties we experienced starkly illustrate how Big Tech and for-profit companies circumscribe how scholars conduct academic, non-commercial research, even on public-domain materials. For instance, despite HathiTrust being a not-for-profit collaborative of academic and research libraries that own the physical copies of the digitized works, we needed special permission from Google to display page image thumbnails on our site, because Google digitized 95% of HathiTrust works in the mid-2000s (“About the Collection”). In our negotiations with HathiTrust, we had to prove that our archive of highly specialized texts about prosody — miniscule in comparison to HathiTrust’s 18+ million volume collection (see figure 2) — wouldn’t compete with Google Books! This example is one of many that exposes the fragility of the current research ecosystem, in which scholars encounter often invisible limitations around who can access these materials, how these materials can be used, and even which materials get included in the first place. 2

Figure 2. Visualization showing the relative sizes of HathiTrust and the HathiTrust items within the PPA.

Our poster will detail the additional levels of data we gained access to by securing Memoranda Of Understandings (MOUs) from these companies (we needed separate MOUs for integrating works into the web application and for conducting computational analysis on the full text). We also invested an immense amount of time and energy into building out their digital infrastructures to meet our needs – and improving them in the process. For instance, Gale/Cengage was eager to partner with us, seeing the specialized PPA as a gateway to more ECCO subscribers and as an opportunity to experiment with adapting their internal API for external use. However, we spent over a year waiting in their development queue for minor yet necessary enhancements to their API so that we could access basic metadata such as volume number and English Short Title Catalog (ESTC) number, which was necessary to link to the more robust MARC records Princeton luckily owned. Similarly, we spent years correcting, refining, and augmenting HathiTrust’s messy and incomplete metadata for thousands of works; however, HathiTrust is not able to accept our corrections because of their understandably limited ability to develop individual workflows with each partner research library.

The PPA imagines a scholarly ideal in which the curation of data is driven by research questions, rather than by profit or by who happens to have digitized what. Rather than developing new resources from scratch, we imagine sharing workflows and ideas with other scholars so as to remove barriers and to work across – rather than just within – our research library’s subscriptions. By visualizing and conveying our story, we encourage scholars to think critically about the digital resources they routinely use in their research, and to reimagine, reinvent, and clamor for new kinds of research infrastructures beyond the walled gardens, including interoperable datasets and cross-institutional data collectives, and to consider anew how we might surface and credit the often invisible labor involved in creating these resources.

While we are talking about openness across resources, there is also a desire for more openness within them. See John A. Walsh et al.’s recent discussion of the challenges of building out HathiTrust Research Center’s Extracted Features dataset to make the non-consumptive analysis it offers more flexible and customizable.

In New Digital Worlds, Roopika Risam discusses the “uneven digitization of literary texts” and calls scholars to recognize “the ways that existing digital archives bear traces of colonialism” (39-40).