1.

Introduction

Translation Alignment is an NLP task within the field of Parallel Text Processing (Véronis 2000). It consists in the establishment of links across texts in different languages at different levels of granularity, such as chapter, sentence, or word level.

In the case of ancient languages, many uncertainties are involved in this operation. Most of the corpora at our disposal consist of literary texts, which are notoriously difficult to translate (Palladino et al. 2021). This task, however, has become increasingly popular in recent years: by leveraging on Large Language Models such as BERT and RoBERTa, several automatic models for the alignment of ancient texts have been developed (Yousef et al. 2022; Riemenschneider and Frank 2023; Krahn, Tate and Lamicela 2023; Reboul 2024). These models have also been applied to the study of the transmission of early modern works (Sprugnoli 2023) and for various downstream tasks, such as Named Entity Recognition (Yousef et al. 2023) and word sense disambiguation (Keersmaekers, Mercelis, Van Hal 2023).

However, LLMs are very data-hungry, and in the domain of ancient languages there is still an enormous lack of training data and Gold Standards to test the performance of these models. In 2023, we published the first Gold Standard with Guidelines for Ancient Greek texts and English translations (Palladino et al. 2023). The corpus includes 5,359 Greek words across the

Iliad, Xenophon’s

Cyropaedia, and Plato’s

Crito. The two annotators who created the alignments were among the very few who, at the time, fulfilled the two most important criteria to participate in the research: they were experienced Classics scholars trained on Ancient Greek and were also familiar with the Ugarit platform and the scientific topic of translation alignment (this was a fundamental prerequisite to design the alignment guidelines). However, they also differed from one another in important ways, especially concerning their additional linguistic abilities: Annotator 1 is an Italian native speaker while Annotator 2 is a Persian native speaker; although their linguistic background is Indo-European and they are both proficient in English as a second language, they also have different levels of familiarity with other languages, such as Latin, German, Avestan, and Old Persian.

After the creation of the corpus and of the Guidelines, Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA) was calculated to assess the consistency and reliability of the methods used and resulted in 86.08%, which is considered high according to traditional standards. Therefore, the Guidelines were able to provide a consistent way of addressing substantial problems, despite the differences between the two annotators. There is, however, still considerable space for improvement. There is approximately a 14% of disagreement that is unaccounted for, and because ancient corpora are not as large as modern corpora, this could have a much more considerable impact on training and evaluation.

In this paper, we present the results of an investigation into the Ancient Greek-English Gold Standard, focusing on patterns of disagreement across the two annotators who created the dataset. Recognizing these phenomena and investigating their cause will give us a better understanding of what parts of the Guidelines were inaccurate or confusing, what relevant phenomena were omitted, and what other factors may affect the creation of similar datasets, such as previous familiarity with the texts, expertise with alignment tools, or even the native language of the annotators. This study will also support further refinement of Alignment Guidelines and will provide an important resource for scholars who are creating similar resources in the domain of ancient or historical corpora.

2.

Results

We extracted all instances of disagreement between the two annotators, including both complete and partial disagreement. This included individual words or phrases where each annotator selected a different match, and tokens that were aligned by one annotator but not by the other one. We assigned specific categories to each instance of disagreement, and calculated the resulting rates. The full dataset is published, with notes and documentation in

https://github.com/UgaritAlignment/Alignment-Gold-Standards/tree/main/grc-eng.

The entire corpus can be visualized interactively at

https://ugarit.ialigner.com/IAA/, and disagreement and unaligned tokens can be highlighted or visualized as a table, alongside specific percentages of IAA for each chunk in the corpus.

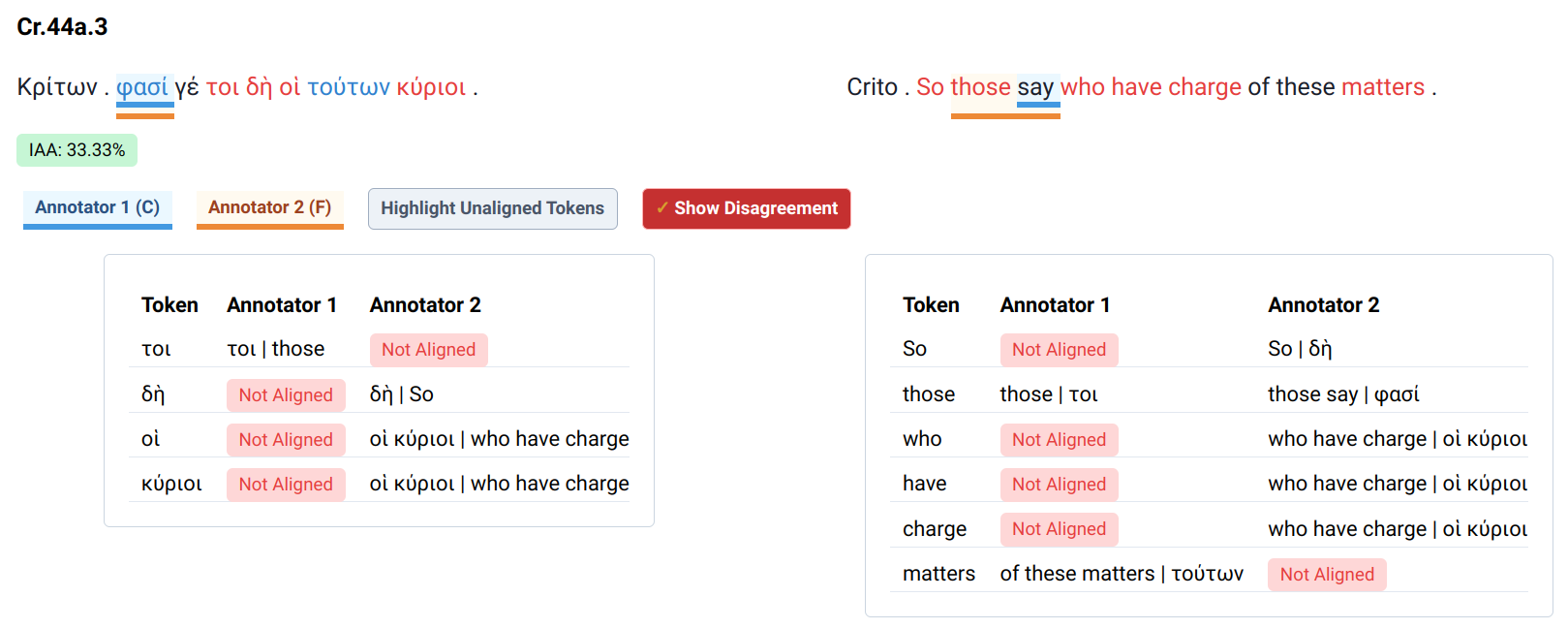

Figure 1. One of the passages with the lowest agreement rate, from

Crito 44a.3. From

https://ugarit.ialigner.com/IAA/.

Overall, there were very few cases where IAA was inferior to 80%. The text that showed the most frequent disagreement, and the highest rate of disagreement by single chunk, was

Crito. This is somewhat counterintuitive, as most of the chunks in

Crito corresponded to speaker’s tags, and were therefore relatively short. However,

Crito is also a dialogue, with a very high percentage of idiomatic and unusual expressions.

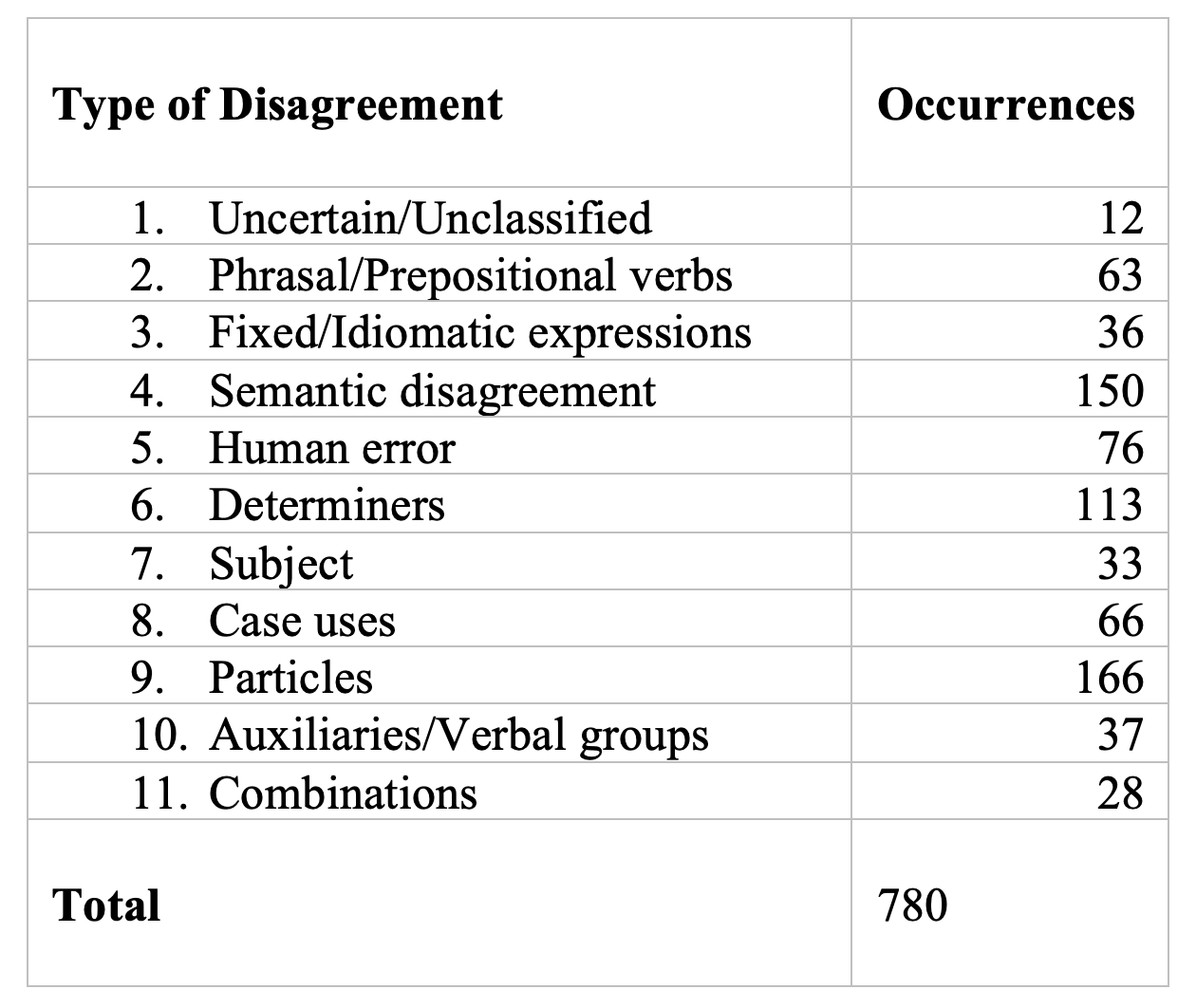

In order to analyze the results at a finer granularity, we introduced labels that identified the type of disagreement between annotators. Although this type of work has been conducted for other types of annotations, most notably Named Entities (Álvarez-Mellado et al. 2021), this is the first time that, to our knowledge, disagreement is analyzed systematically in manually annotated parallel corpora (Table 1).

The labels addressed categories of disagreement that were explicitly noted in the Guidelines, but also other causes, such as disagreement in translation equivalency and human error. The labels were defined as follows:

- Uncategorized/Uncertain: where the disagremeent did not fit any of the categories provided.

- Phrasal or prepositional verbs.

- Complex, fixed, or idiomatic expressions in Greek.

- Semantic disagreement: this rather broad label identified all cases where the two annotators matched the same tokens in the source text with different tokens in the target text, due to an ambiguity in the English translation.

- Human error.

- Determiners, including all uses of the articles (including articular infinitives and substantivized participles) and most pronouns.

- Subject, considering all cases where the subject was aligned (or not) against the indications of the Guidelines, likely due to the interpretation of the annotator.

- Case use.

- Functional particles.

- Auxiliaries/Verbal groups: when the target text used an auxiliary to render a specific verbal construct, such as passivization, tense, or mood, causing a disagreement between the annotators.

We also considered a minority of “combinations”, where two or more categories of disagreement co-occurred. In total, there were 27 of such cases, plus one “super-combination”, where auxiliary, phrasal verb and idiomatic expression appeared all as sources of disagreement in the expression “τὸν νοῦν προσέχει” (“does he pay attention” vs. “he pay attention to”).

Table 1. Number of disagreements per category.

Cases of semantic disagreement and the presence of particles or determiners were the cause of the vast majority of issues, accounting for about half of the total. Some recurring phenomena, however, can be detected across the board:

- Regarding determiners, a recurrent source of disagreement (15 cases) was the use of the article as a pronominal equivalent, a phenomenon typical of the

Iliad but absent in the rest of the corpus.

- Substantivization was another recurrent source of disagreement: it occurred in 24 cases, 9 of which were participles.

- Most disagreements in the “particles” category were caused by δέ, μέν, καί and τε, which are also the most frequent ones in Greek texts. These are functionally very important in Greek, but their translation is very challenging and often connected to other parts of the clause, or even dependent on the specific dialect.

- Another major source of disagreement was the inclusion (or lack thereof) of ἄν in the alignment (18 cases). Notably, the presence of ἄν also affected 13 combinations with semantic disagreement.

- Many cases of semantic disagreement (61) were caused by the lack of match in one of the two annotators, who judged certain translations not close enough to the original to be aligned. Annotator 1 showed a decisively stricter tendency to this pattern than Annotator 2 (45 cases against 17).

Certain constructs were more prone to generating inconsistency across the board. Prepositional verbs and case uses seem to point to a general discomfort in associating English prepositions with Greek constructs. It is difficult to say whether this is due to a generally strict approach of the two annotators or to the fact that English was not their native language, which may have affected their attitude towards English prepositional constructs. The presence of a participle typically affected agreement in many different areas, including semantic disagreement, determiners due to substantivization, idiomatic constructs and even the inclusion of an explicit subject or of auxiliaries.

3.

Conclusion

Having set aside cases of obvious distraction or error, there were situations where the Guidelines either caused confusion or ignored certain aspects of the text. The phenomenon of implicit constructions with the omission of the main verb, although rather common in Greek, was not addressed specifically in the guidelines, and therefore led to inconsistencies (8 cases in total). Verbal adjectives were a peculiar recurrent source of disagreement (3 cases, of which 2 regarded the word πρακτέον), as they were not explicitly addressed in the Guidelines.

Disagreement, however, occurred regularly wherever the guidelines relied on the individual judgment of the annotator. Some occurrences, however, may be further specified to ensure more consistency: all types of prepositional constructs, including phrasal verbs and case uses, should more explicitly address lexical equivalence between English and Greek. This was also notable in the case of determiners, where the judgment of individual annotators caused disagreement every time the guidelines allowed it, i.e. wherever a determiner was not translated exactly according to the lexical definition: Annotator 2 tended to be a lot more flexible in the establishment of translation equivalents than Annotator 1, who did not align many determiners where the translation did not correspond morphologically (often in case and number). This may even be because the native language of Annotator 2 does not use articles, resulting in overcompensation in the creation of translation equivalents.

Participles were addressed carefully in the Guidelines, but were still a major source of disagreement. This is partly because the translation of Greek participles is so varied and unpredictable that it is very difficult to address every possible case. However, many instances also show evidence of distraction or inconsistency by the annotator: in these cases, it is also important for Guideline authors to emphasize the challenging nature of these constructs, and recommend that annotators pay special attention to these instances.

Finally, the context of an alignment matters more than initially anticipated. Dialect and period of the text were not considered in the Guidelines, which aimed at being as general as possible: but this also caused recurrent inconsistencies that can be addressed explicitly with more accurate instructions.