This presentation offers a critical evaluation of the use of the Web Mercator projection to visualise and present humanities and heritage data. How can a consideration of the historical processes that formed collections inform the design of web maps? To address this question, the collection amassed by Hans Sloane in the eighteenth century acts as an example. Including botanical materials, antiquities, books and manuscripts, amongst other items, the collection was gathered together from across the globe by a broad set of intermediaries that included colonial administrators, traders and the enslaved. Digital records of these objects are the subject of the Sloane Lab project, funded by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council. The Sloane Lab’s knowledge base (SLKB) is a rich and interconnected knowledge graph representation of this vast collection that ‘models collecting practices that often systemically silenced the voices and methods of knowledge production of people and cultures that were collected’ (Nyhan et al. 2023). Ongoing research as part of a Sloane Lab community fellowship links and visualises records of British Museum and British Library objects using web maps. The aims here are two-fold:

-To explain why the use of Web Mercator in this context is problematic from visualisation and historical perspectives.

- To introduce alternative projections and provide technical guidance for their application in web mapping technologies.

1.

Web Maps, Mercator and the Digital Humanities

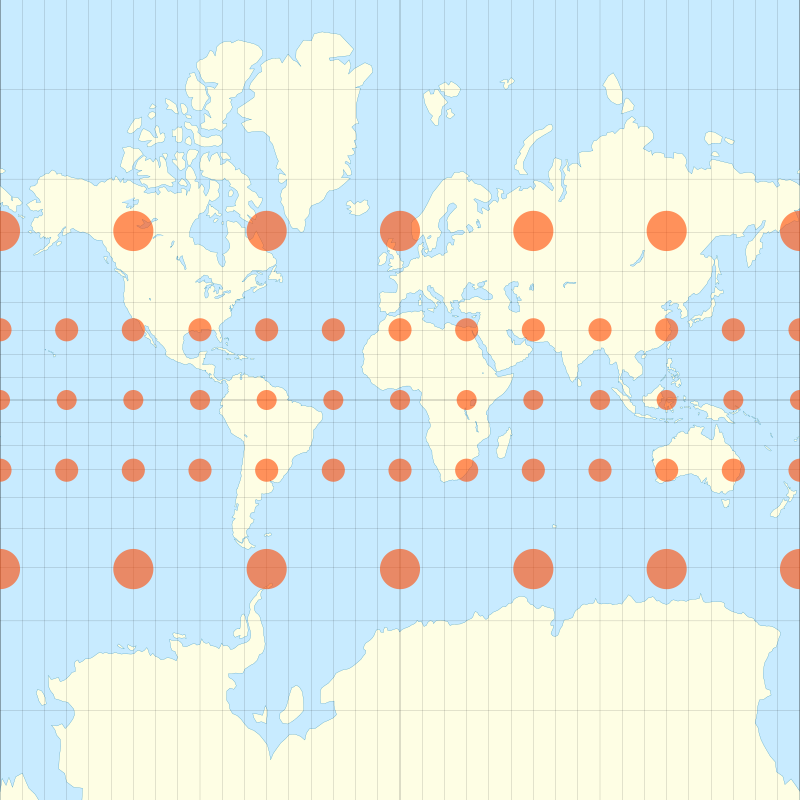

A set of web map components, including Google Maps Embed API, Open Layers, Leaflet.js and MapBoxGL, draw on a constrained set of features including projection, tiles, markers and popups. Being relatively straightforward to implement and supporting exploration and browsing without preconceived queries, their wide application in the digital humanities has been a cornerstone of the spatial turn (Dunn 2019: 5). Geography is intimately connected with identity and thus maps offer powerful opportunities for visual analysis and engagement with humanities data by researchers and the wider public (Rees et al. 2022). Yet, whether web maps can present the ‘complexity and diversity of cultural collections, and to privilege the process of interpretation’ and be defined as ‘generous’ in Mitchell Whitelaw’s terms (2015: 46) requires investigation. A mature and reflective use of this technology should acknowledge that users have preconceptions, not least through web maps’ widespread application in navigation and business advertising (McQuire 2019). Projection is fundamental to the appearance of the web map, governing the position of markers and tiles and thus strongly influencing visual analysis. The Web Mercator projection predominates due to its preservation of angles and association with ‘hyper-local’ navigation (Presner et al. 2014: 108). Yet it is unsuitable for the aims and scope of Sloane Lab, first, due to well-documented visual compromises —the inflation of landmasses at high latitudes like Europe at the expense of others like Africa and the Caribbean— that not only hamper visual analysis but also recreate and reinforce global inequities and injustices. Second, the Mercator projection has a history, entangled with processes like colonialism, empire and slavery that also shaped Sloane’s collection (Monmonier 2004).

Figure 1. Map of the world based on Mercator projection including indicatrices to visualise local distortions to area. By Justin Kunimune. Source

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mercator_with_Tissot%27s_Indicatrices_of_Distortion.svg Used under

CC-BY-SA-4.0 license.

2.

Development-led approach

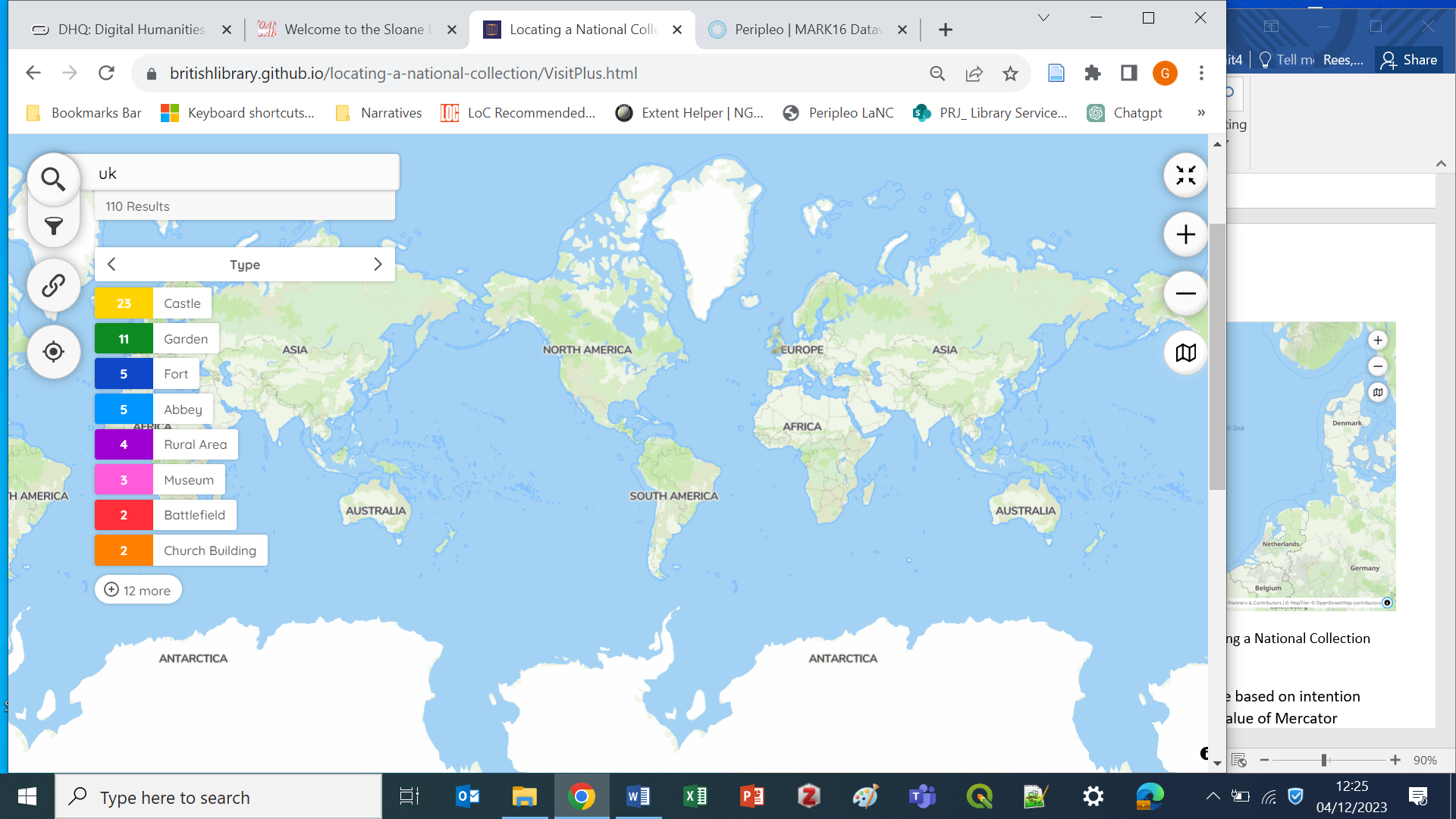

A development-led approach will examine alternatives to Web Mercator through the geography of Hans Sloane’s collection. This draws on the methods and tools of the Pelagios Network, the latter a community of researchers developing Linked Open Data methods for the humanities and cultural heritage. A subset of the SLKB that includes British Museum and British Library objects with suitable geographical information will be aligned with World Historical Gazetteer. This subset forms the basis of a JSON-LD dataset based on standards including GeoJSON, Web Annotation and Pelagios’ Linked Places that will first be visualised using Peripleo web map software and Web Mercator. Web map components including Leaflet, Open Layers and MapBoxGL offer the opportunity to visualise data through different projections and the presentation will outline issues in their application such as open-source or proprietary, implementation of projections and technical requirements.

Figure 2. Peripleo web maps interface based on Web Mercator. Available at

https://britishlibrary.github.io/locating-a-national-collection/VisitPlus.html

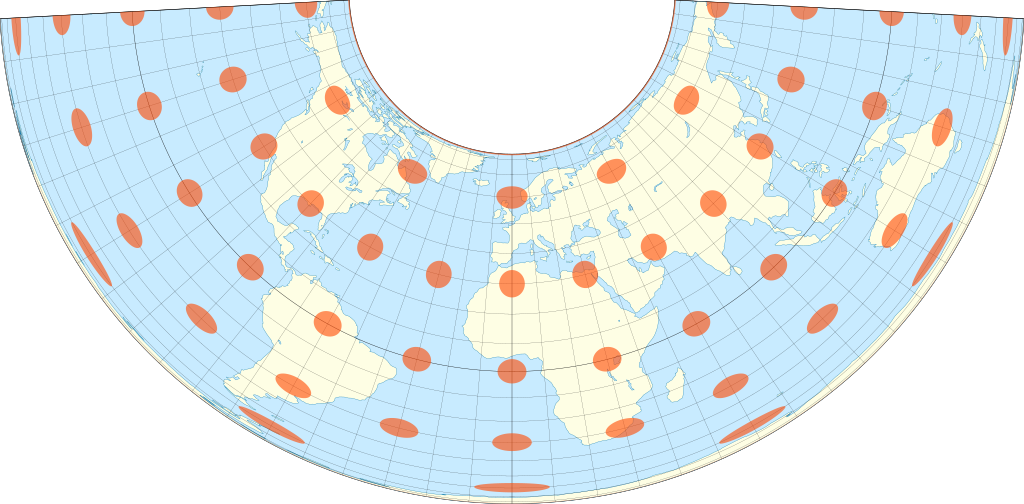

All projections require compromises and projection selection should be based on intended use and geography depicted. From a purely visual perspective, the value of Mercator varies based on map scale or zoom level, geographical area and the intended use of the map. The subset of Sloane’s collection spans the Atlantic including Europe, Africa and the Caribbean and the suitability and the implementation of several projections for this specific collection and geography will be explored. Intentionally preserving area gives the regions where collecting occurred visual prominence. Preserving distance does justice to the passages that objects and those who collected them took, often across the Atlantic. Issues in implementing equal-area, equidistant and compromise projections such as Equidistant Cylindrical and Albers Equal Area will be introduced. Such projections have rarely been implemented in digital humanities, heritage or related fields, although a few examples exist (Kahn / Bouie 2021).

Figure 3. Map of the world based on Albers equal-area projection including indicatrices to visualise local distortions to area. By Justin Kunimune. Source

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albers_with_Tissot%27s_Indicatrices_of_Distortion.svg Used under

CC-BY-SA-4.0 license.

3.

Implications and potential

This presentation is part of wider ongoing research that encourages digital humanists to look beyond the current state of web mapping practice. Although a heritage collection is used as an example, the findings readily apply to cultural or historical research data. In laying out visual and historical issues alongside practical guidance for implementing alternative projections, the aim is to support thought-provoking and creative reinvention of a commonly-used visualisation form and foster responsible engagement with researchers and wider public communities. Moreover, stakeholders have a responsibility to those who were involved in the creation of collections but remain uncredited (Ortolja-Baird / Nyhan 2022). Geography provides insights into identity meaning places recorded within the SLKB offer a window into who was involved in collecting practices. Engaging with the history of visualisation forms offers vital opportunities for digital humanists to invigorate engagement.