1.

Introduction

Stylometry was first applied to establish chronology of texts (Lutosławski 1897) and then became a preferred tool of computational authorship attribution beginning at least with Mosteller and Wallace (1964). These and many later studies found that counting most frequent words (MFWs) such as pronouns, modals, articles and prepositions is enough to group texts by author, but that other “signals” such as those of translator, genre, chronology or gender can influence patterns of similarity and difference (Rybicki 2014, 2017, 2022).

It is not at all surprising that this approach to texts – which allows computation of any number of texts – merged with another tendency to “read” as many written products of human culture as is humanely impossible yet computationally possible: Moretti’s distant reading soon moved in the direction of “macroanalysis” (Jockers 2013). Criticized from various positions (Drucker 2017, Mandell 2019), it still remains a way to ask questions to literary “big data” that cannot be answered by traditional close reading because there are simply too many books around.

While most of this research has been done on the dominating English-language literature, its usefulness obviously does not end there. This study strives to show the advantages of this approach within the Polish literary tradition.

2.

Material

We have produced a digital literary collection of more than 10,000 full Polish texts for the purpose of stylometry and distant reading. This is the largest collection of Polish literature in ready-to-analyse format. In comparison, the National Corpus of the Polish Language – made, as it is, for very different tasks – is only based on 2,500 books, including non-fiction, and ca. 340 press titles. Still, it is important to note the limits of representativeness as the contents of the collection were conditioned by a number of historical “filters:” others’ decisions in the past to print, translate, digitize, to produce digital copies of acceptable quality; and finally the contemporary decision to include in this collection.

Contrarily to many other similar attempts, the Polish collection presented here contains both public-domain and copyrighted texts, and an almost equal number of original Polish texts and those translated into Polish from 23 other languages.

The collection contains texts by 1682 authors (original: 674, translated: 1019) and by 1735 translators; 105 of Polish authors are also translators. It is annotated with basic textual metadata such as author and translator names and dates, first (Polish) publication dates, author and translator sex, first place of publication, etc. The earliest texts date back to the turn of the 14

th and the 15

th century, and the latest text is of 2022; statistically-reliable numbers of texts appear in late 18

th century. In the future, this collection will be fully open-access (either in full-text mode or, in the case of copyrighted material, as frequencies of required lexical units).

3.

Methods

This study combines metadata analysis of the large-scale collection in the original distant reading mode with stylometry based on MFW frequencies, to see if large-scale collections of literary texts such as the one used in this study, in combination with their metadata and simple semantics (such as “content” rather than “function” word occurrences), may provide better insight into the relative strengths of the various “signals.”

The study adopts the well-tested workflow (Eder 2017) which combines most-frequent-word analysis of the texts produced with the stylo package (Eder et al. 2016) for R with network analysis with Gephi to produce a large network, or map, of this Polish collection, where proximity between each pair of texts reflects the similarity in Mfw usage. Various results of metadata and semantics counts were then mapped onto this network.

4.

Results

For lack of space, only the main results are discussed here.

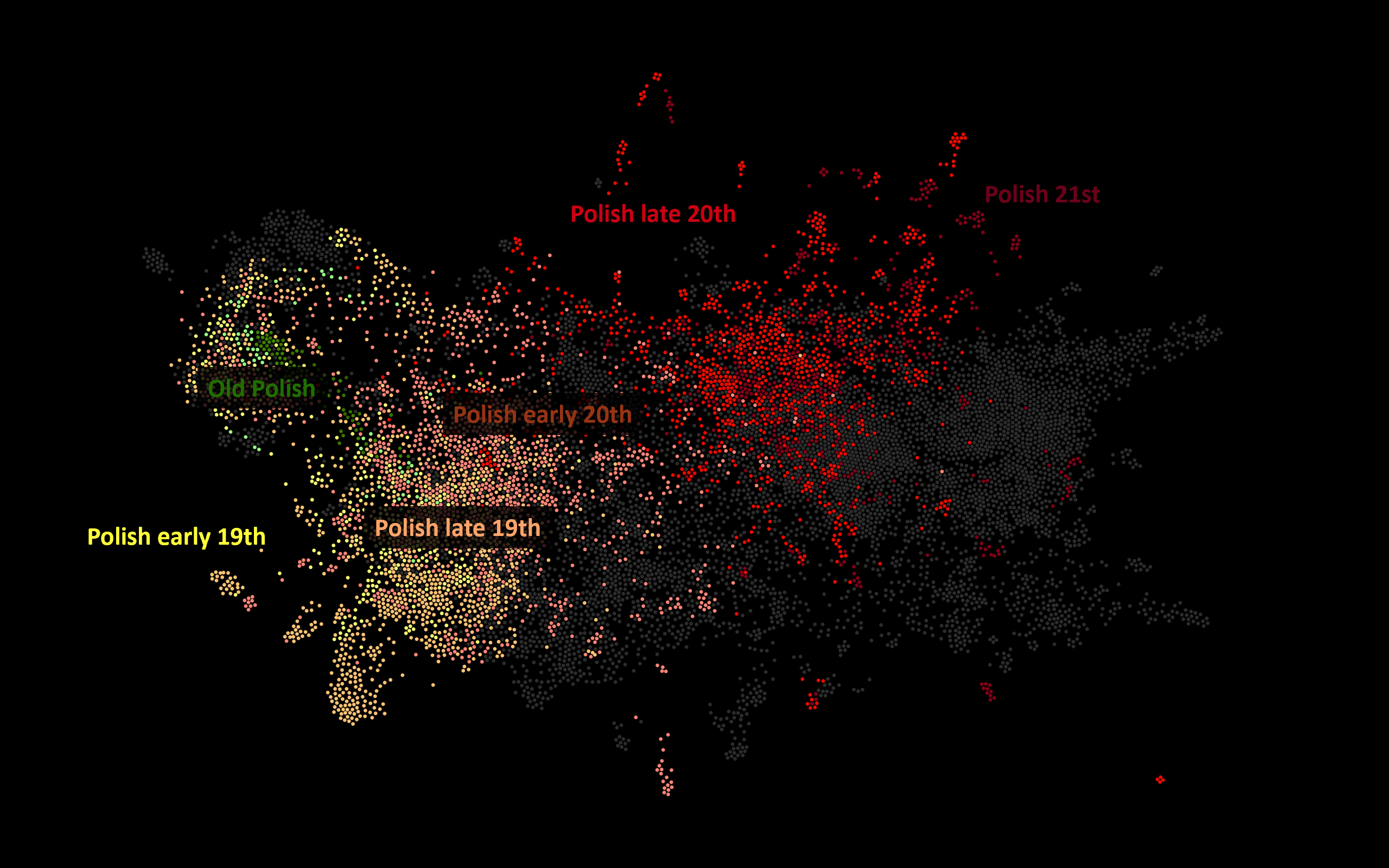

The oft-observed phenomenon where comparison of the usage of MFWs is enough to elicit a chronological progression within any collection of texts can be easily recreated with Polish originals in a network analysis (Figure 1).

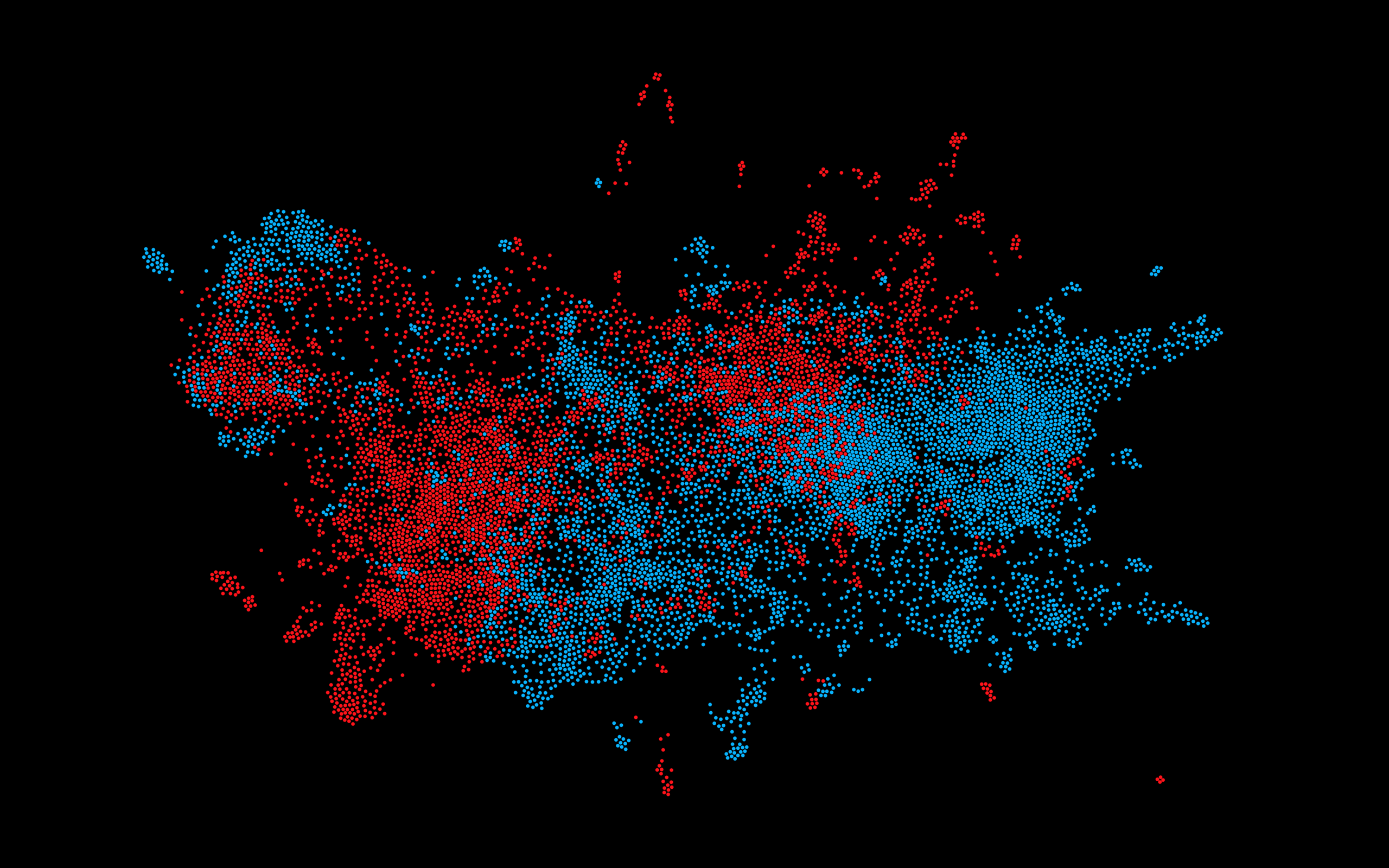

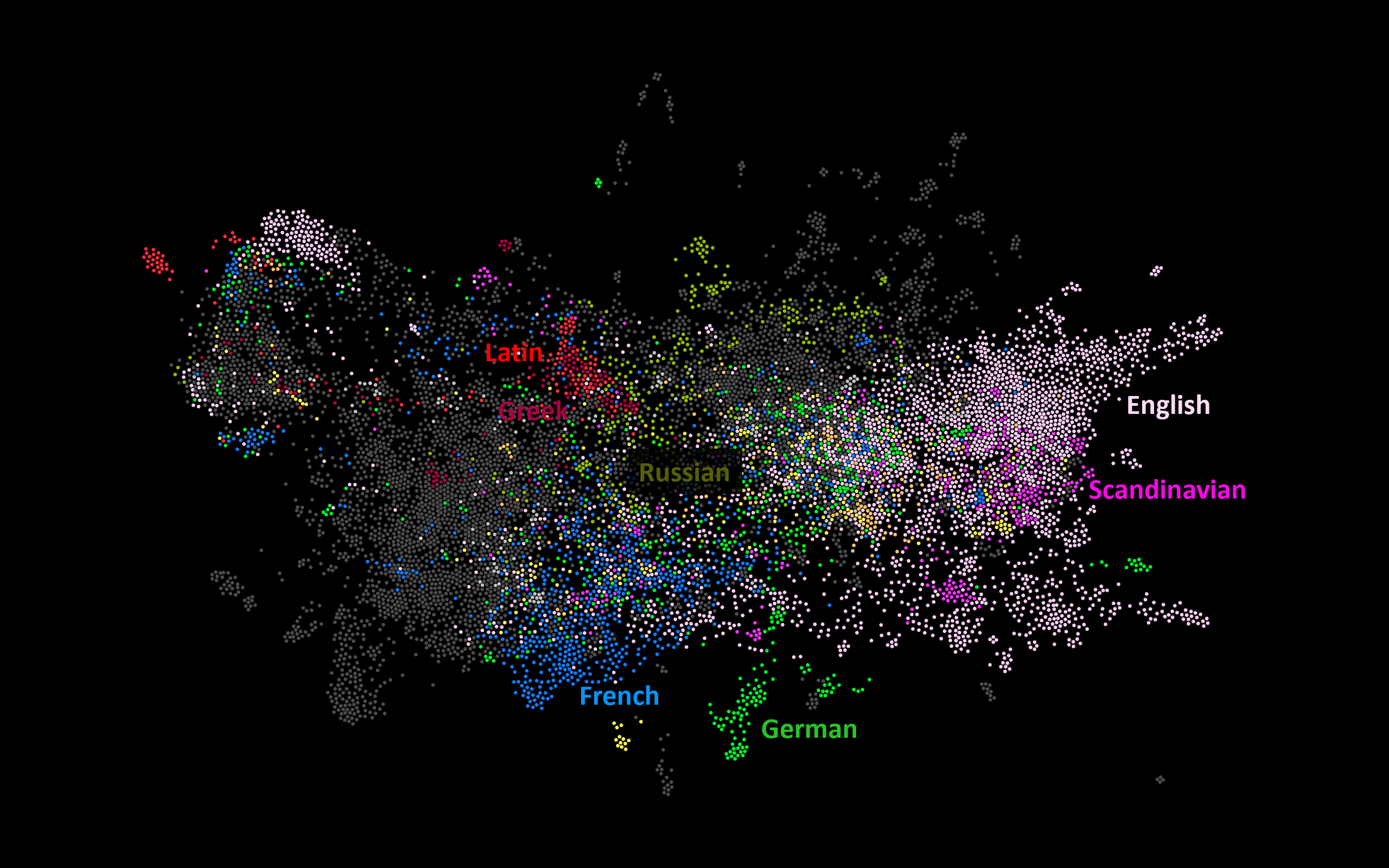

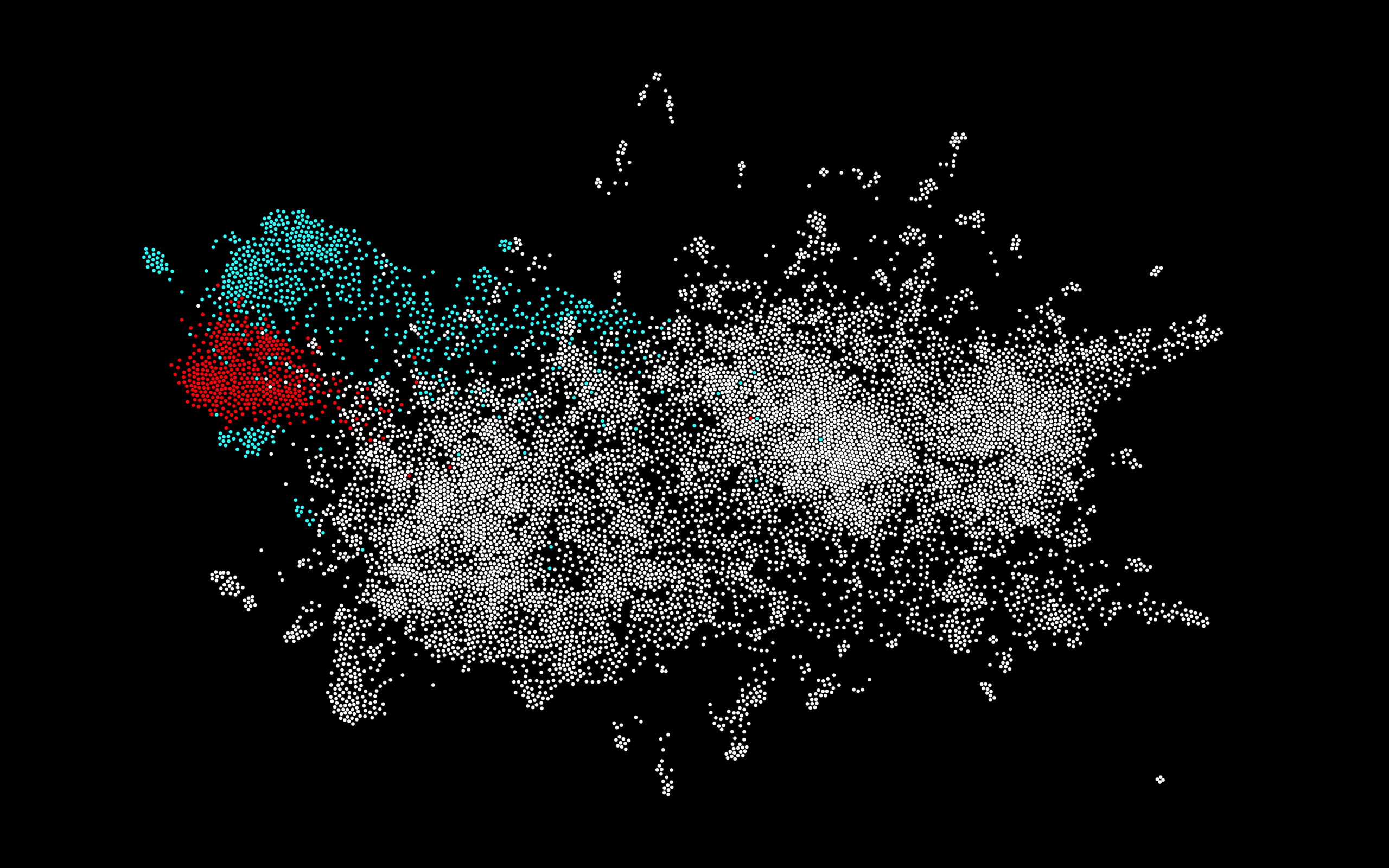

Figure 2 shows the same network, now classified as originals and translations. There is a clear division into original and translated literature, somewhat complicated by the signal of genre (see below). This presents good evidence of the existence of what can be called stylometric translationese: differences in word usage between original and translated texts. What is more, translationese seems at least partially further classifiable according to source language. This is visible in Figure 3, where different colors have been applied to translations from the main source languages in the collection. It should be noted, again, that the smaller communities of the same colors appearing in the left part of this graph are due to differences in genre; this becomes evident after comparison to Figure 4.

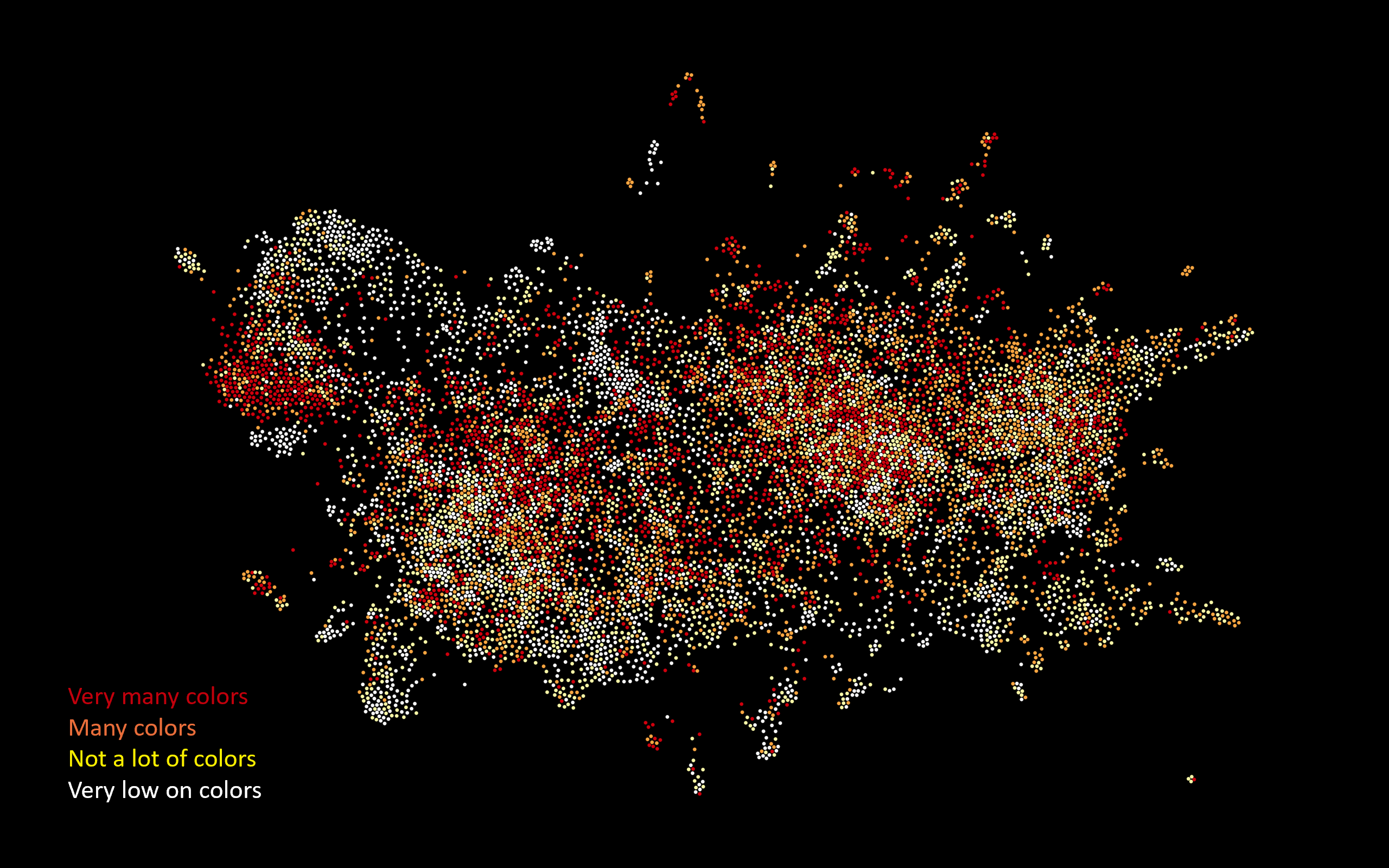

Mapping keyword (“content word”) data onto the same networks creates other interesting possibilities. In Figure 5, the count of all words denoting colors in the collection’s texts allows classifying each text on a “color-words” quartile scale; when this is overlaid with the MFW-based network, poetic texts (left) not only share similar most-frequent-word usage proportions, but also constitute the most “colorful” community. Interestingly, the same part of the network consists of texts in the highest quartile of love-and-sex-related terms, making poetry a genre that combines color and love! Meanwhile, the community of dramas largely coincides with the least colorful texts.

Other results include:

- A steady chronological growth of the number of texts by women within Polish literature, significantly higher than in literature translated into Polish; in combination with earlier studies (Rybicki 2014, 2017, 2022), this shows a better gender balance in native Polish literature rather than gender bias against women in selecting texts for translation.

- In the last two decades, there are more female than male translators.

- Contrary to earlier studies based on limited library data, which pointed to the emergence of English as the most-translated literature in Poland only in the 1930s (Krajewska 1972), English literature occupied that position well into the 19th century.

- The pro-Russian communist takeover of Poland after WW2 resulted in a decade of Russian dominance among translations; the end of communism in 1989 led to a decisive domination by English originals.

- Sentiment analysis of this collection, based on a large language model trained on literary texts (Strzałka 2021), shows an initial higher percentage of positive emotions expressed in translated texts; native Polish texts reduce this distance in the final quarter of the 19th century, coinciding with a trend in Polish literature called (for very different reasons) positivism.

5.

Discussion

Our data and our specific results make this large-scale distant-reading/stylometric approach worthwhile, at least from a Polish-studies perspective. But there is more: this may be away to breach the traditional division between world’s (mainly post-colonial) “major” literature and their more modest relatives: in this perspective, all literatures become much more comparable and thus comparative. This gives us the new hope to lay to rest the two-centuries old imperial (and indeed imperialist) bias that “minor literatures may be—not neglected, but passed by with courteous excuse, by the comparative historian… But to the general student they are at most facultative, and the general historian on a limited scale can hardly spare them a faculty of competing” (Saintsbury 1907: 403).

6.

Acknowledgement

This research has been funded by the Jagiellonian University’s Flagship Project “Digital Humanities Lab.”