The

International Council of Museums (

ICOM) has defined the responsibility of museums to research and preserve both tangible and intangible heritage (ICOM 2010). This responsibility, ratified by ICOM’s General Assembly, is embedded in the Ethical Guidelines, which stipulate the need for complete and accurate documentation of an artifact’s provenance—detailing its journey from creation or discovery to its status. In this context, provenance research is an indispensable tool for confirming the authenticity of cultural artifacts and potentially supporting ownership disputes of contested museum objects. It is critical to the ethical curation and management of cultural assets, ensuring that the history of artifacts is communicated to the public with clarity and transparency, thereby maintaining trust in the preservation of cultural heritage. The increased scrutiny of museum collection documentation has led to a widespread re-examination of the legitimacy of collections—a discourse that is taking place in both the public and professional spheres. Despite progress, the field still faces many challenges: accurately documenting artifacts’ histories and harmonizing practices for managing and protecting information.

This study uses digital methods to address the challenges of cultural heritage management. It examines the prevailing research landscape in museums, using the example of 45 collections (or departments) of 14 institutions, identifying shortcomings and suggesting directions for future improvement. The study takes an interdisciplinary approach, combining statistical analysis with qualitative approaches from the humanities, such as art-historical provenance research. The museums’ data is extracted from their websites using web scraping; in this context, nine categories are created, e.g., to assess the chronology of provenance data.

1.

Methodology

Digital provenance research is increasingly focused on improving cataloging systems and promoting the interoperability of data through standardized terminologies (Hopp 2018; Fuhrmeister / Hopp 2019; Haffner 2020; Rother et al. 2022). Lang (2023) also stresses the need to catalog knowledge gaps. Nevertheless, previous work remains theoretical or limited to specific projects, such as the German

Lost Art Foundation’s research database (Haffner 2019); there is a gap in the systematic, quantitative analysis of provenance data in museum databases.

To fill this gap, our study revolves around three analytical perspectives, refined into nine sub-categories based on the scope of national guidelines (Yeide et al. 2001; Andratschke et al. 2018):

-

Publication dimension: Is provenance information actively disseminated digitally? Is it visible and accessible to the public? The sub-categories are

Object Identity,

Bibliography,

Chronology, and

Uncertainty.

Object Identity focuses on the most essential metadata as defined by the Arbeitskreis Provenienzforschung e.V., such as artist and title.

Bibliography and

Chronology confirm the inclusion and sequential order of bibliographic details and ownership records;

Uncertainty assesses the unambiguity with which indeterminate data is presented.

-

Interactive dimension: Is the provenance information digitally linked? The sub-categories

Referenceability and

Searchability measure the interconnectedness of provenance data.

Referenceability assesses the linking of common metadata fields to similar objects;

Searchability examines whether provenance information can be queried in full-text or faceted search tools.

-

Technological dimension: How is provenance information stored and represented digitally? We focus on

Uniformity,

Completeness, and

Standardization in the documentation of provenance-related data, i.e., the person, date, place, and type of acquisition.

Uniformity and

Standardization examine the consistent formatting of data across records;

Completeness ensures that all data elements are captured.

We quantitatively assess

Object Identity,

Bibliography,

Chronology,

Uncertainty,

Referenceability, and

Searchability and qualitatively assess

Uniformity,

Completeness, and

Standardization. Percentages and ordinal scales are used for the former categories and Likert scales for the latter.

2.

Data

Our study analyses (excerpts from) 45 publicly available museum collections (or departments) of 14 institutions in Germany and the United States, selected for their different organizational and financial structures and varying degrees of data quality and volume.

In the selection process, care was taken to ensure that the geographical, temporal, and material dimensions of the collections were comparable to allow comparisons both within and between the museums. We excluded museums without an online database, museums that did not record provenance data or make it publicly available, and museums where acquisition information was only available in the form of credit lines. Although the intention was to include smaller museums, this was often constrained by the selection criteria. The representativeness of the sample was therefore based on factors such as regional diversity, organizational structure, and collection focus. In Germany, institutions such as the

Berlin State Museums

1

and the

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud

2

in Cologne were selected; US counterparts include the

Detroit Institute of Arts

3

and the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

4

.

Web scraping is used to systematically extract the museums’ data required for the analysis. We use Python 3.12 with the libraries

asyncio and

aiohttp. The methodological workflow is as follows:

- The first step is to identify a starting URL pattern. This is often the primary URL of a digital collection, where access to individual object pages is facilitated by a search interface. For collections that use sequential indices, we estimate the highest index to systematically record the object URLs.

- Comprehensive querying of object pages from each institution is then conducted, with the data being extracted and compiled into a JSONL file. This process emphasizes capturing the general structure of the web pages, focusing on elements like tables and table-like structures where the first column typically represents the name of the metadata field and the second column its value.

- The final step is to standardize the non-standard field names so that the data can be analyzed consistently. This involves mapping each key in the JSONL file to a predefined field name.

3.

Results

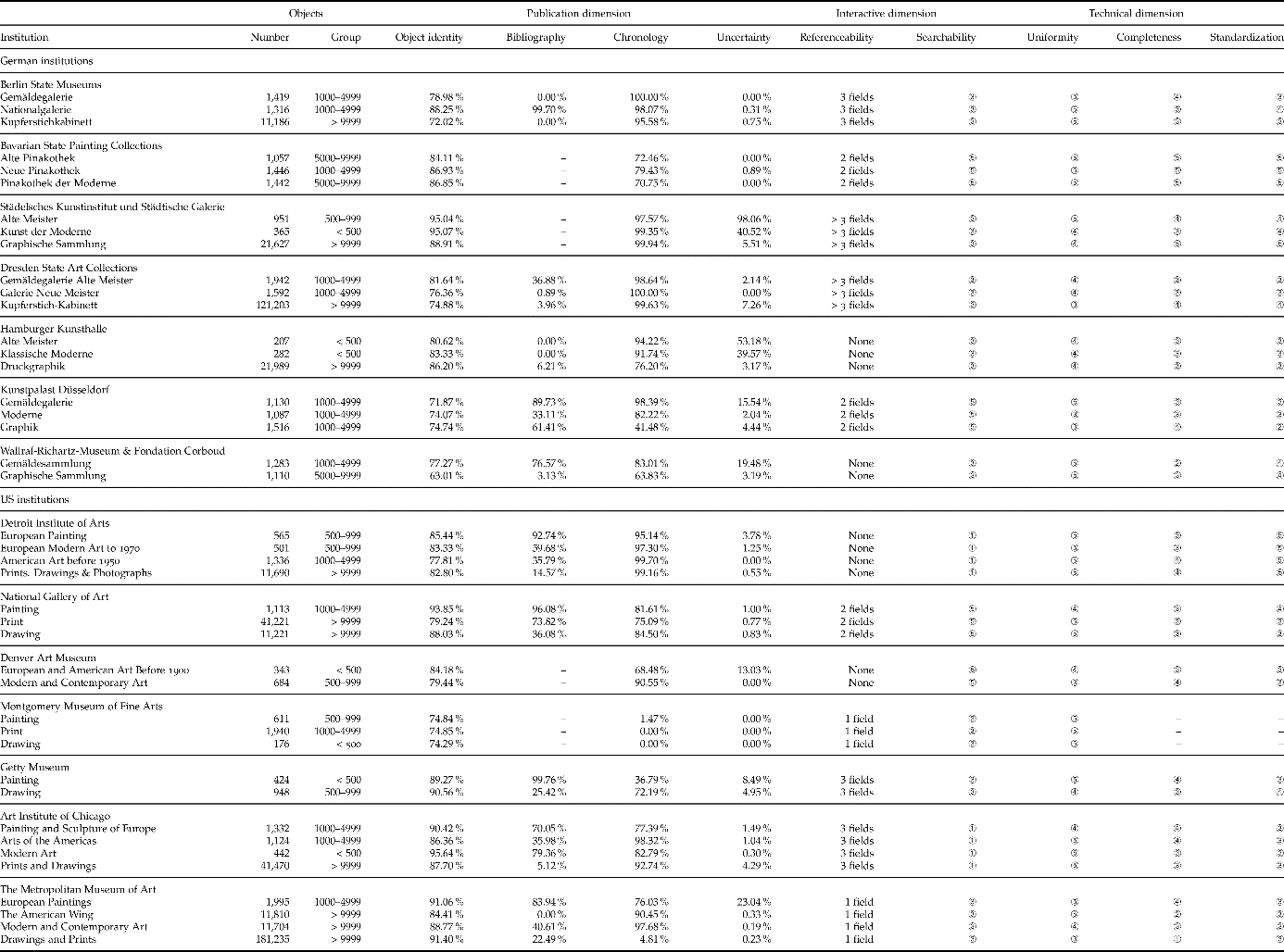

The study’s findings, based on afore-introduced analytical perspectives and summarized in Tab. 1, are as follows:

-

Publication dimension: With n=30, a predominant number of collections have consistent documentation of

Object Identity for most of their items (at least 80 %). Conversely, bibliographic documentation is completely absent in 19 collections and marginally present (up to 25 %) in 7 collections, resulting in significant knowledge gaps. While most collections (n=26) follow a chronological format in their provenance records for most objects (at least 80 %), there are notable variations, particularly in the omission of acquisition dates.

-

Interactive dimension: German museums uniformly provide basic full-text search capabilities, ensuring a basic level of

Searchability. In contrast, many US collections (n=8) show significant deficiencies in this aspect.

Referenceability is also significantly underrepresented in most US collections (n=16), with only a few exceptions.

-

Technological dimension: Except in a minority of cases (n=7), data in almost all collections do not conform to uniform, complete, or standardized recording. In particular, the recording of data in terms of

Completeness and

Standardization is often found to be suboptimal.

Fig. 1: Analysis of nine sub-categories in 45 publicly available museum collections (or departments) of 14 institutions in Germany and the United States.

Inconsistent use of standardized vocabularies such as the

Gemeinsame Normdatei (

GND) and

Virtual International Authority File (

VIAF) exacerbates these problems. In our view, the root cause of these inconsistencies can be traced back to the organizational frameworks within museums. Furthermore, it is plausible to assume that the discrepancy between internal data collection and its public availability contributes to the identified shortcomings.

5

Based on our analysis, we recommend the following actions:

-

Technical Level: There is untapped potential within

Database Management Systems (

DBMS) such as

MuseumPlus. We suggest the implementation of uniform back-end schemas for precise input regulation. The approach taken by the

Bavarian State Painting Collections is commendable: it segments provenance data, allowing for technical validation of inputs, such as standardizing the treatment of uncertain or ambiguous data. This practice should be extended to other data types, such as acquisition categories, where back-end inputs could be designed to automatically recommend relevant field values to ensure data consistency.

-

Structural and Organizational Level: The focus should also extend to improving data management processes, advocating streamlined workflows. These workflows could be reconfigured to reflect natural operational sequences: e.g., the introduction of audit trails is essential to monitor changes in provenance data, increase transparency, and enable discrepancies in records to be traced back to their source. It is also important to ensure the interoperability of DBMS. This facilitates the smooth integration with a wide range of research tools, databases, and external repositories, which is essential for fostering cross-institutional collaboration.

Further qualitative analysis through questionnaires with museum staff is underway to identify potential solutions. The importance of conferences bringing together academics and museum professionals cannot be overstated: initiatives such as the “FAIR-CARE-te Welt” workshop at LMU Munich in 2023 are crucial in this regard. The careful recording and sharing of provenance data is fundamental to a thorough and critical assessment of collecting practices, especially when dealing with the legacy of contexts of unjustness. This underscores the moral imperative of provenance research and the need for comprehensive investigations into historical contexts marked by violence. The quality of research data thus becomes crucial and serves as the cornerstone for transparent, accurate, and detailed provenance documentation, which emphasizes the importance of sustainable resource management for cultural heritage.

Appendix A

Bibliography

-

Andratschke, Claudia / Hartmann, Jasmin / Poltermann, Johanna / Reuter, Brigitte / Schmeisser, Iris / Schöddert, Wolfgang (2018):

Leitfaden zur Standardisierung von Provenienzangaben. Hamburg: Arbeitskreis Provenienzforschung e. V. <https://wissenschaftliche-sammlungen.de/files/4515/2585/6130/Leitfaden_APFeV_online.pdf> [09.05.2024].

-

Fuhrmeister, Christian / Hopp, Meike (2019): “Rethinking Provenance Research”, in:

Getty Research Journal 11: 213–231. DOI: 10.1086/702755.

-

Haffner, Dorothee (2019): “Provenienzforschung digital vernetzt. Ergebnisse sichtbar machen”, in:

Museumskunde 84: 90–97 <https://www.museumsbund.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/museumskunde-2019-1-online.pdf> [09.05.2024].

-

Haffner, Dorothee (2020): “Provenienzen in Sammlungsdatenbanken. Digitale und virtuelle Chancen für die Vermittlung”, in:

Provenienz & Forschung. Digitale Provenienzforschung: 36–42.

-

Hopp, Meike (2018): “Provenienzrecherche und digitale Forschungsinfrastrukturen in Deutschland: Tendenzen, Desiderate, Bedürfnisse”, in: Blimlinger, Eva / Schödl, Heinz (eds.):

…(k)ein Ende in Sicht. 20 Jahre Kunstrückgabegesetz in Österreich. Schriftenreihe der Kommission für Provenienzforschung 8: 35–59. Vienna, Cologne: Böhlau. DOI: 10.7767/9783205201274.37.

-

ICOM, ed. (2010):

Ethische Richtlinien für Museen von ICOM. Zürich: ICOM <https://icom-deutsch-land.de/images/Publikationen_Buch/Publikation_5_Ethische_Richtlinien_dt_2010_komplett.pdf> [09.05.2024].

-

Lang, Sabine (2023): “Mind the Gap. Von Lücken in der Provenienzforschung und ihrer Präsenz im digitalen Raum”, in: Busch, Anna / Trilcke, Peer (eds.):

Abstracts zur 9. Jahrestagung des Verbands Digital Humanities im deutschsprachigen Raum e.V. „DHd2023: Open Humanities, Open Culture“, 212–217. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7688632.

-

Rother, Lynn / Koss, Max / Mariani, Fabio (2022): “Taking Care of History. Toward a Politics of Provenance Linked Open Data in Museums”, in: Fry, Emily L. / Canning, Erin (eds.):

Perspectives on Data, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. DOI: 10.53269/9780865593152/06.

-

Yeide, Nancy H. / Akinsha, Konstantin / Walsh, Amy L. (2001):

The AAM Guide to Provenance Research. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Museums.