1.

Abstract

In our talk we analyze the gender gap in the German literary canon. We present an overview on general tendencies of the gender divide in Marcel-Reich-Ranicki’s “Canon of world literature” (Marcel-Reich-Ranicki-Canon-Corpus / MRRCC) and shed light on the question whether attempts to focus female representations in special editions such as Gutenberg’s “strong women volume” (SWV) actually help to reduce gender representation bias.

2.

Background

By presenting a small selection from the great amount of literary texts, reading lists provide a certain degree of guidance for readers. Thus a canon influences the formation of shared cultural knowledge (Hermann 2012: 60). One consequence can be the suppression of non-selected texts from cultural memory leading to their forgetting (Pfohlmann 2005: 27). The selection made in reading lists is accompanied by an evaluation (Anz 2007: 208) that characterizes literature as worthy or unworthy of being passed on. In the Digital Humanities it has been stated that gender bias is deeply rooted in (canonized) data (cf. D’Ignazio and Klein 2020) and that it is necessary to identify this bias in order to reduce it (cf. Göritz et al. 2022). In the Digital Humanities there has been a lot of work on the topic of gender representation aiming at the identification of biases. We connect directly to this kind of work being done in Computational Literary Studies focussing English (cf. Kraicer and Piper 2019, Underwood et al. 2018, Baylog et al. 2016, Jockers and Kiriloff 2016), French (cf. Vianne and Barré 2023, Argamon et al. 2009) and Dutch (cf. Koolen 2018, Smeets 2021) fiction and add a German perspective to these works.

3.

Corpus

Following these approaches we analyse one of the most prominent examples of a German literary canon, which is Reich-Ranicki's canon of "world literature". This study ties in with the need for analyses of larger corpora (Heydebrand 1990: 383) by analyzing this canon with regard to gender aspects. From Reich-Ranicki’s canon of world literature we chose German prose texts from the 18th–20st century. Altogether the MRRCC includes 129 prose texts from 26 authors, 25 of them being male and 1 female. We then compare the outcome with data gathered from a second corpus in the same way. The strong women volume edited by project Gutenberg contains 8 novels from 7 authors, 3 of them being male and 1 female. The novels written by male authors in this volume share the feature of the protagonist being female.

4.

Method

To automatically annotate “female”, “male” and “neutral” gender roles in our corpus we used a gender classifier we developed in previous research (Schumacher 2021) which uses CRF-algorithms developed by the Stanford NLP group. (cf. Manning et al. 2015). The classifier reaches an average of 79% F1-score. Using this method we are able to automatically annotate most of the nominal references to characters in German literary fiction. However, it does not cover references via pronouns, character descriptions or actions. So unlike Underwood et al. we do not analyse proportions of character descriptions in novels. It is also not possible in the limited scope of this paper and with the chosen method to dive deeper into the analysis of character constellations like Piper and Kraicer (2019) and Smeets (2021) do. But, by excluding pronouns from our classification and not tracing back nominal depictions to characters they refer to we are able to move away from a binary distinction of gender towards a tripartite system in which characters can be referred to with nouns implying different genders depending on the context. Thus the focus of this paper is not the analysis of fictional characters as individuals but the way characters are referred to most often.

5.

General Findings

Within the entire corpus, 107,710 male, 43,213 female and 7,521 gender-neutral roles were annotated, which shows that in the MRRCC male roles are most dominant. With 67,89% of all mentioned gender roles being male this corpus even shows a larger gender-gap than the 2:1 ratio Piper and Kraicer named “the golden mean of patriarchy” (Kraicer and Piper 2019, 3). Focussing on roles that occur more than 100 (female, neutral) respectively 300 times (male) in the entire corpus, we come to the following results.

5.1.

Neutral gender roles

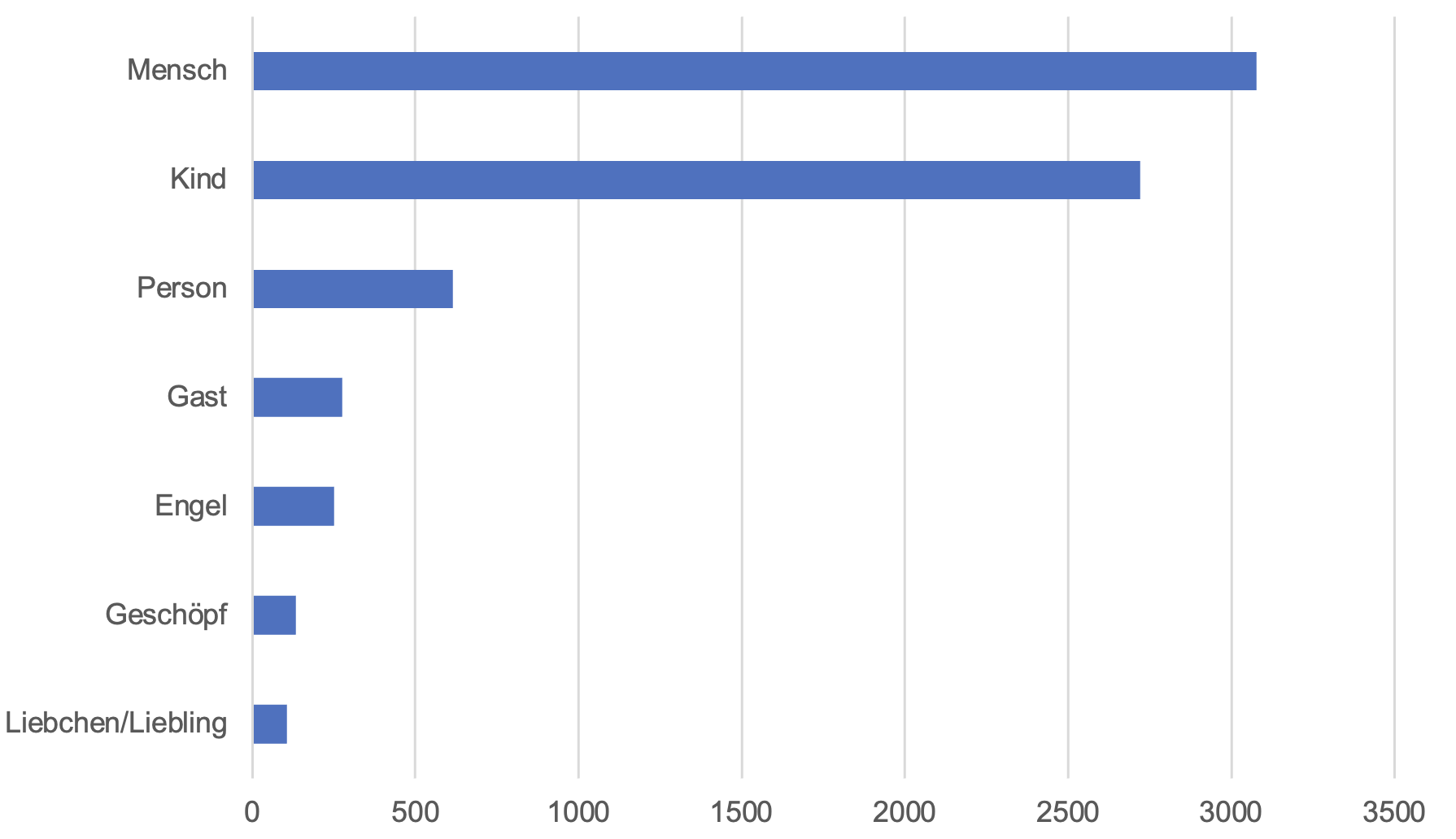

Figure 1: Most frequent gender-neutral roles

Among the gender-neutral roles, the general classification as "human" (“Mensch”) and "person" (“Person”) occur most frequently. In addition, the term "child" opens up a familial setting. "Guest" refers to neutral roles with temporary character, while "angel" can be interpreted as a religious reference or term of endearment. Among neutral character references nicknames or swear words are also quite often.

5.2.

Female gender roles

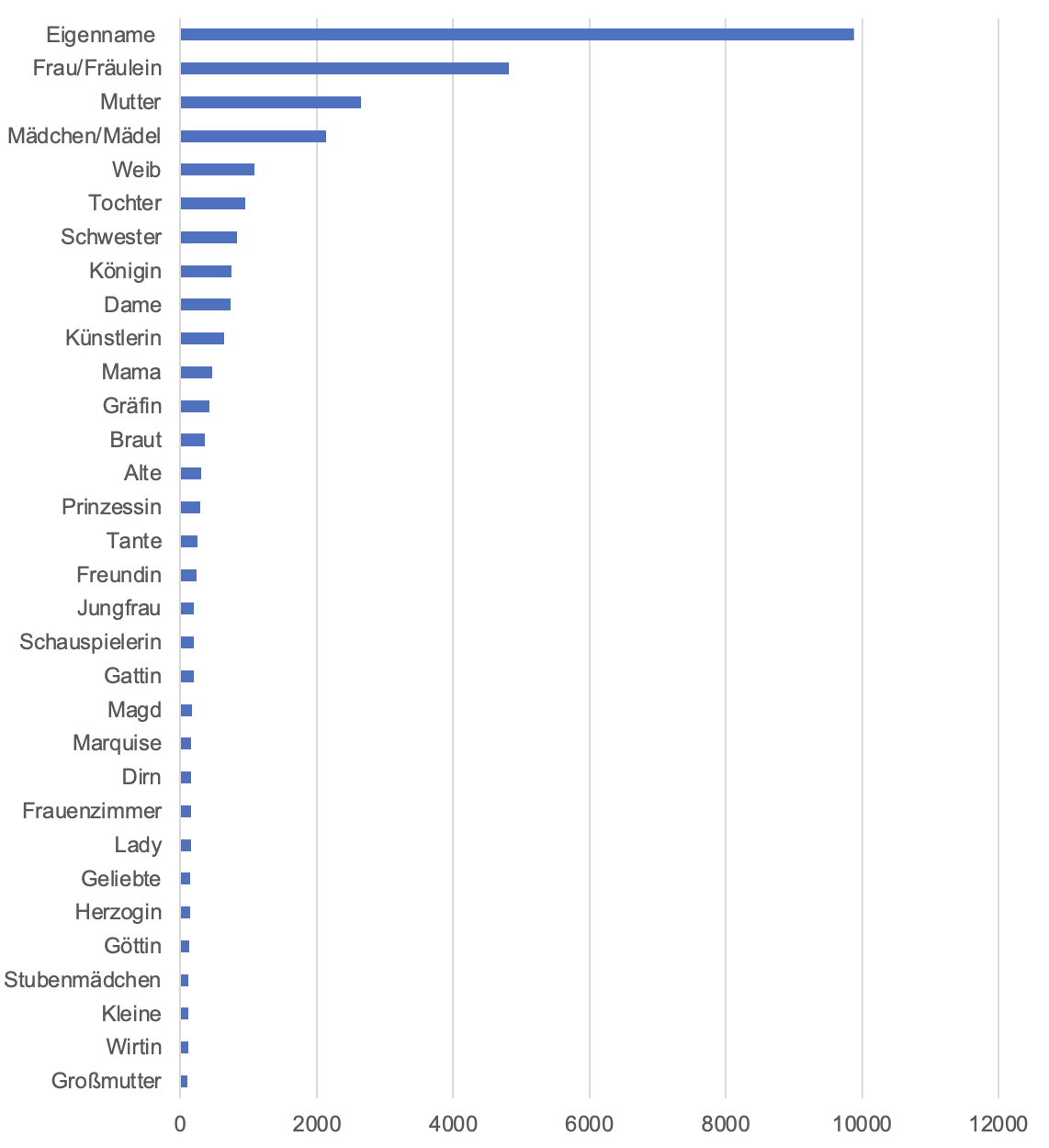

Fig. 2: Most frequent female roles

The female role profile is made up of four main areas: Roles that refer to biological sex (e.g. “woman”/“Frau”), roles that refer to a profession or social status (e.g. “queen” / “Königin”), roles that identify female roles as part of a family (e.g. “mother” / “Mutter”) an) (fig. 2). Most female gender roles are identified by reference to biological sex (9,076), followed by roles that refer to the family setting (5,801). The third largest field consists of roles from the area of profession/status (3,287). A small number of female roles are defined as part of a relationship (698).

5.3.

Male gender roles

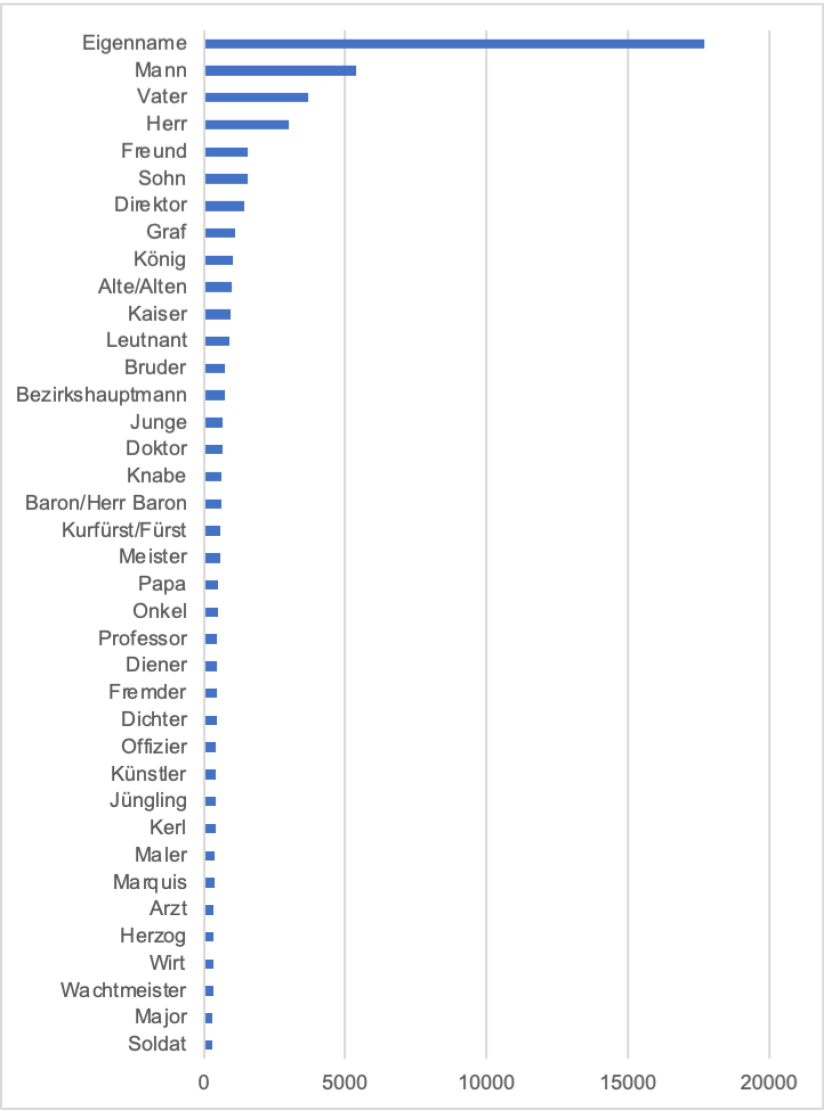

Fig. 3: Most frequent male roles

In the male gender profile of the MRRCC proper nouns also occur with high frequency. Apart from that male roles are primarily characterized by the attribution of a role from the professional sphere (13,360, e.g. “director” / “Direktor”). In the second place are roles defined by the attribution of biological sex (10,517, e.g. “man” / “Mann”). Roles from the area of family (e.g. “father” / “Vater”) are least strongly represented (6,984). Roles that are defined by the biological sex refer to passive roles to which the gender role is ascribed by birth. Roles that can be assigned to the field profession/social status are active, empowering roles. If agency is understood as the ability or power of individuals to act (Geiger 2016: 43) this shows that in our corpus, male roles not only outnumber female roles but also have a higher degree of agency.

5.4.

Outliers

Only in one case the number of mentioned female roles is higher than the one of male and neutral roles. This is Schnitzler’s

Sterben. Among the 129 texts 11 texts show a profile with a relatively balanced number of mentioned male and female roles (neutral roles are marginal). Altogether Schnitzler shows the highest tendency to bridge the gender gap closely followed by Fontane. However one has to keep in mind that the MRRCC is not a balanced corpus. Seven texts show an extremely strong gender gap; two were written by Schiller and one each by Goethe, Lessing, Hoffmann, and Roth. However, this leaves us with 111 texts of the MRRCC with an average gender representation bias, which is also characterized by a clear dominance of mentions of male gender roles.

5.5.

Gender depiction in Gutenberg’s strong women volume

Does publishing edited volumes like Gutenberg’s “strong women”-volume (SWV) help reduce the gender representation bias? The short answer is: yes. But neither a pure shift towards female authors nor a pure shift towards female protagonists is the key to reducing bias. In two texts of Gutenberg’s SWV there is a dominance of male gender roles. In five texts there is nearly a balance between female and male depictions. One text shows more mentions of female gender roles. Altogether 12,184 mentioned gender roles are male, 8,974 are female and 1,258 neutral. So whereas in the MRRCC 67,98% of all mentioned gender roles are male, 27,27% are female and 4,75% are neutral in the SWV male roles take up 54,35%, female 40,03% and neutral 5,61%.

6.

Conclusion

In this case study we found out how deep the gender gap between male, female and neutral gender references is in a German literary canon. Our analysis shows a clear 68 : 27 : 5 male-female-neutral gender gap. We showed how a more balanced depiction of gender can be reached by publishing edited volumes like Gutenberg’s SWV.

Mareike Schumacher, Prof. Dr., works as a professor for Digital Humanities at the University of Stuttgart. In 2022 she published her first book on the topic of place and space in novels. Her research interests include Computational Literary Studies, Digital Gender Studies, Narratology, Ecocriticsim and Public Humanities.

Marie Flüh, M.Ed., is a research assistant at the Institute for German Studies at the University of Hamburg. Currently, she is involved in the DFG-Project CompAnno (Comparative Annotation to Explore and Explain Text Similarities). Her interests in research and teaching revolve around Computational Literary Studies, emotions in literary texts, Didactic and literature of the 18th, 19th and 20th century.