Digital humanists recognize the significance of bibliographical metadata in representing works in their historical context (e.g., Bode 2017). The development of digital libraries empowers scholars to “draw together data from a mass of libraries around the world” (Pettegree 2010: 354), and large online bibliographical repositories provide unprecedented possibilities for “distant reading” of metadata, enabling the analysis of book history at scale. However, such studies have predominantly focused on Western contexts (e.g., Lahti et al. 2019; Schmidt 2017; Tolonen et al. 2019). The study of non-Western book history continues to be underrepresented in digital humanities, with limited exceptions such as Vierthaler (2016).

To tackle this issue of global inequities, our study adopts a comparative methodology to analyze large corpora of 16th–19th century Chinese and English language books. We creatively “reinvent” our approach by integrating the material and content aspects of books, and pose the following questions: (1) How did the materiality of books change across this four-century period? (2) What was the historical relationship between the materiality and content of books? (3) How did these results vary between Chinese and English language books?

We collected MARC (machine-readable cataloging) records (The Library of Congress 2023) from the HathiTrust digital library for all Chinese-language books published between 1500 and 1899 C.E. based on the August 1, 2023 version of “Hathifiles” (HathiTrust 2023). We then merged these records with the HathiTrust Research Center Extracted Features Dataset (EF Dataset, Jett et al. 2020), resulting in a corpus of 12,622 Chinese-language works. Additionally, we established a control group of English-language books published in the same period, creating a corpus of 640,659 English-language works.

For each work, we gathered the numbers of volumes, pages, and tokens from the EF Dataset. Since a work may contain multiple volumes with varying sizes, we utilized regular expressions to extract the “maximum dimension” information from the MARC field 300-c (“dimensions”) to facilitate consistent comparison of book sizes. For subject categories, we extracted main classes from the Library of Congress Classification. Specifically for Chinese-language books, we collected subject divisions in the “fourfold classification system” ( sibu fenlei fa 四部分類法) from the 65X and 880 MARC fields (“Subject Added Entry,” “Index Term,” and “Alternate Graphic Representation”). Here, manual mapping was used because the data is not normalized. The “fourfold classification system” was widely employed to categorize books in premodern China and was used in dynastic histories and the largest book collection in imperial China, the Complete Writings of the Four Repositories ( Siku quanshu 四庫全書). The translation of the system and the four division names, “Classics” ( jing 經), “Records” ( shi 史), “Masters” ( zi 子), and “Collections” ( ji 集), referenced Gandolfo (2020).

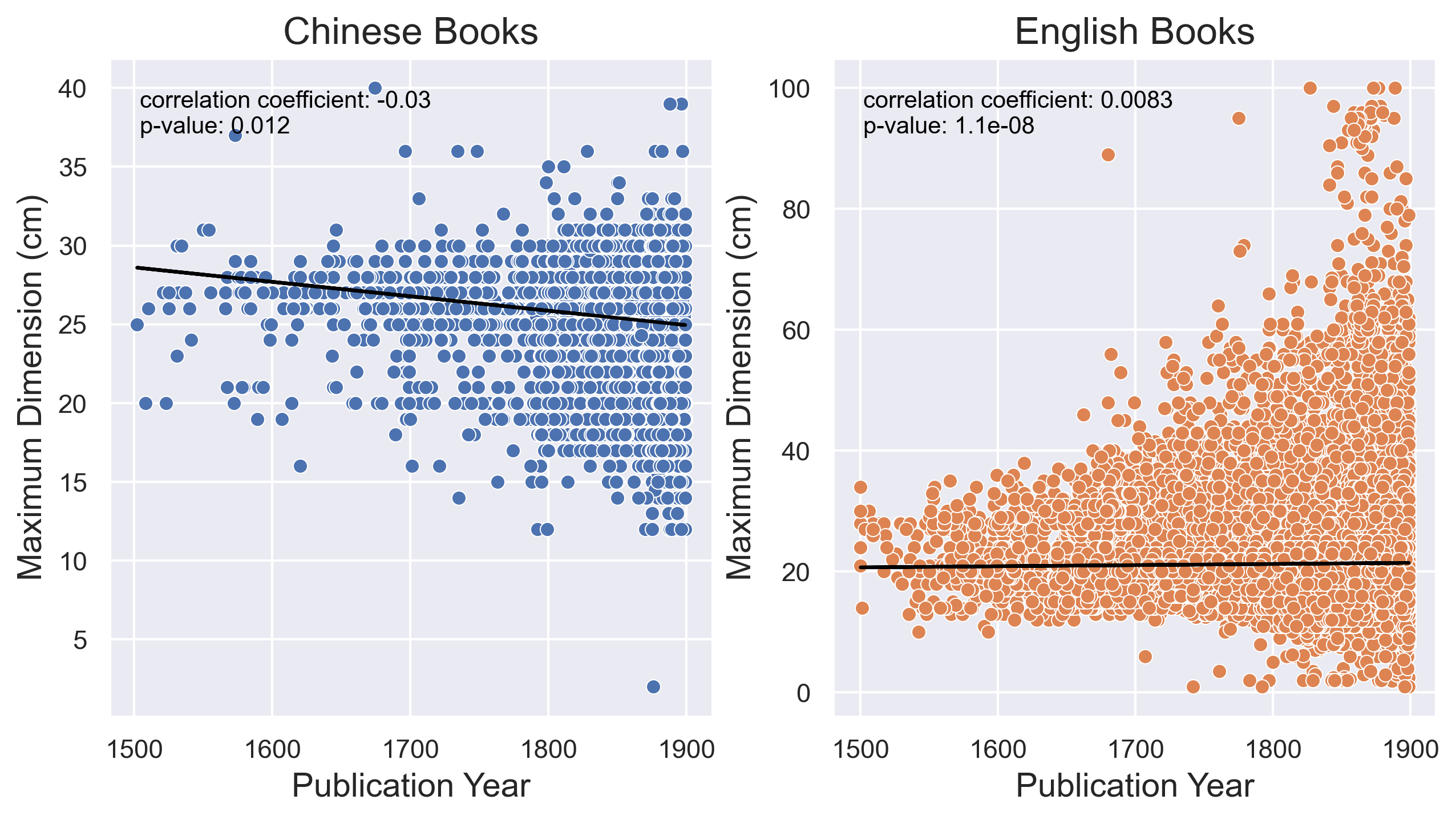

Figure 1 illustrates a decreasing trend in the sizes of Chinese-language books and an increasing trend in English-language books. Although the correlation coefficients are small, suggesting the relationships between publication year and maximum dimension for books in both languages are weak, the small p-values indicate that these relationships are statistically significant. Our prior study on 16th–18th century books revealed a consistent negative relationship for Chinese-language books, while no significant relationship was observed for English-language books (Shang, Cordell, et al. 2023). The inclusion of 19th-century books altered the results for English-language books, likely due to the rapid improvements in the papermaking techniques in the West during that period (Barrett et al. 2022). In contrast, the Chinese publishing industry largely remained unchanged.

Figure 1. Variations in book size in the 16th–19th century Chinese and English language books

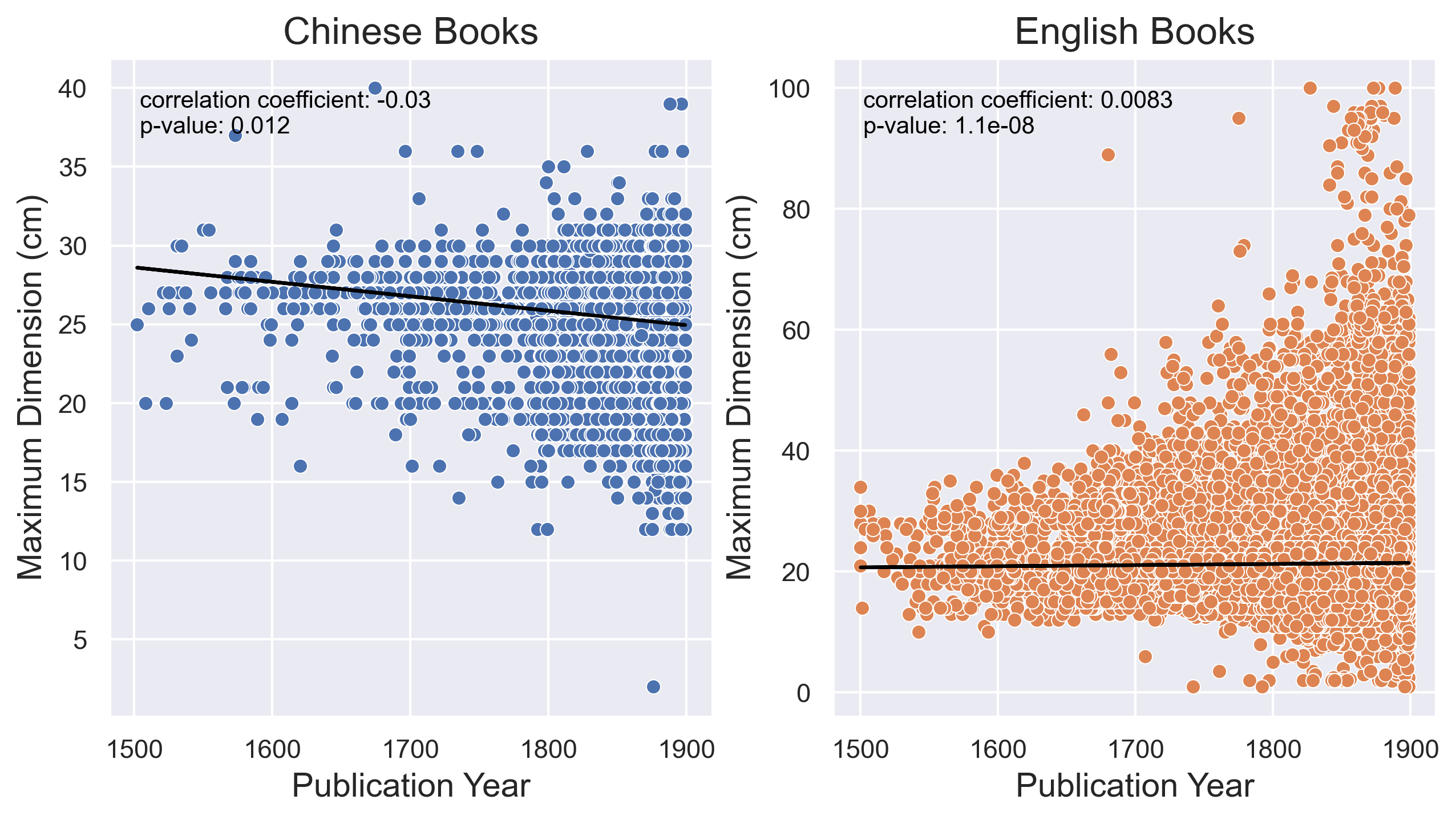

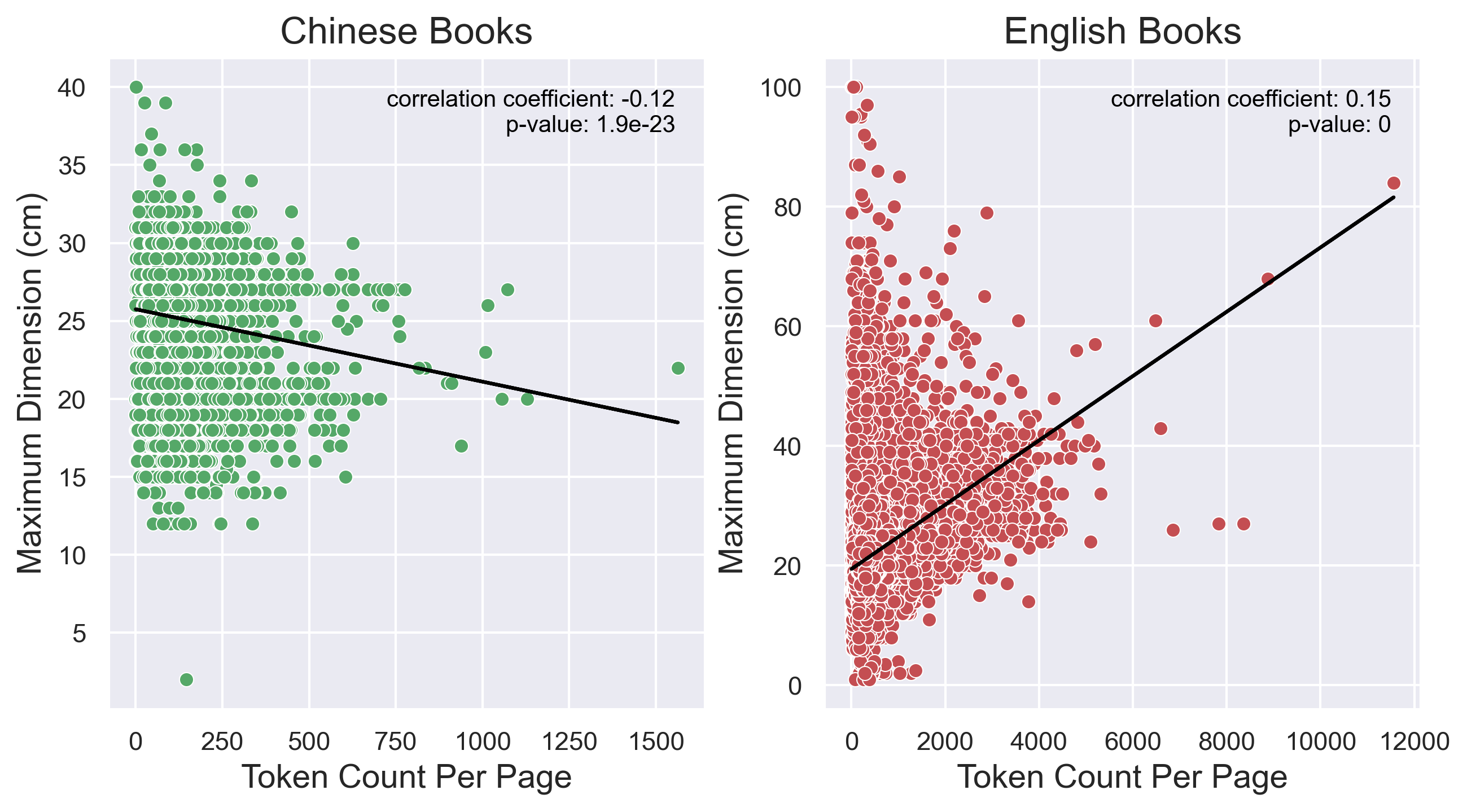

Figure 2 demonstrates a negative relationship between token count per page and maximum dimension for Chinese-language books but a positive relationship for English-language books. While one might anticipate larger books to contain more information per page, as is the case for English books, this relationship is reversed for Chinese-language books. This implies that larger sizes were used to print luxury books in larger fonts rather than to accommodate more characters. Vierthaler (2016) drew the same conclusion based on 1550–1799 Chinese books in WorldCat (https://www.worldcat.org), where he observed a very weak positive relationship. Our results, based on data over a more extended period from another digital library, further suggests a negative relationship, strengthening the arguments of Hegel (1998) and Vierthaler (2016) that the decrease in the physical size of Chinese books was correlated with the decline of their social prestige, indicating a trend toward cheaper mass publication.

Figure 2. Relationship between book size and token count per page in the 16th–19th century Chinese and English language books

Finally, we trained machine learning models to classify subject categories based on material characteristics. Utilizing eight widely-adopted machine learning algorithms available in scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al. 2011), we consistently employed undersampling techniques to balance the classes and selected the algorithm that exhibited the highest performance, the random forest model.

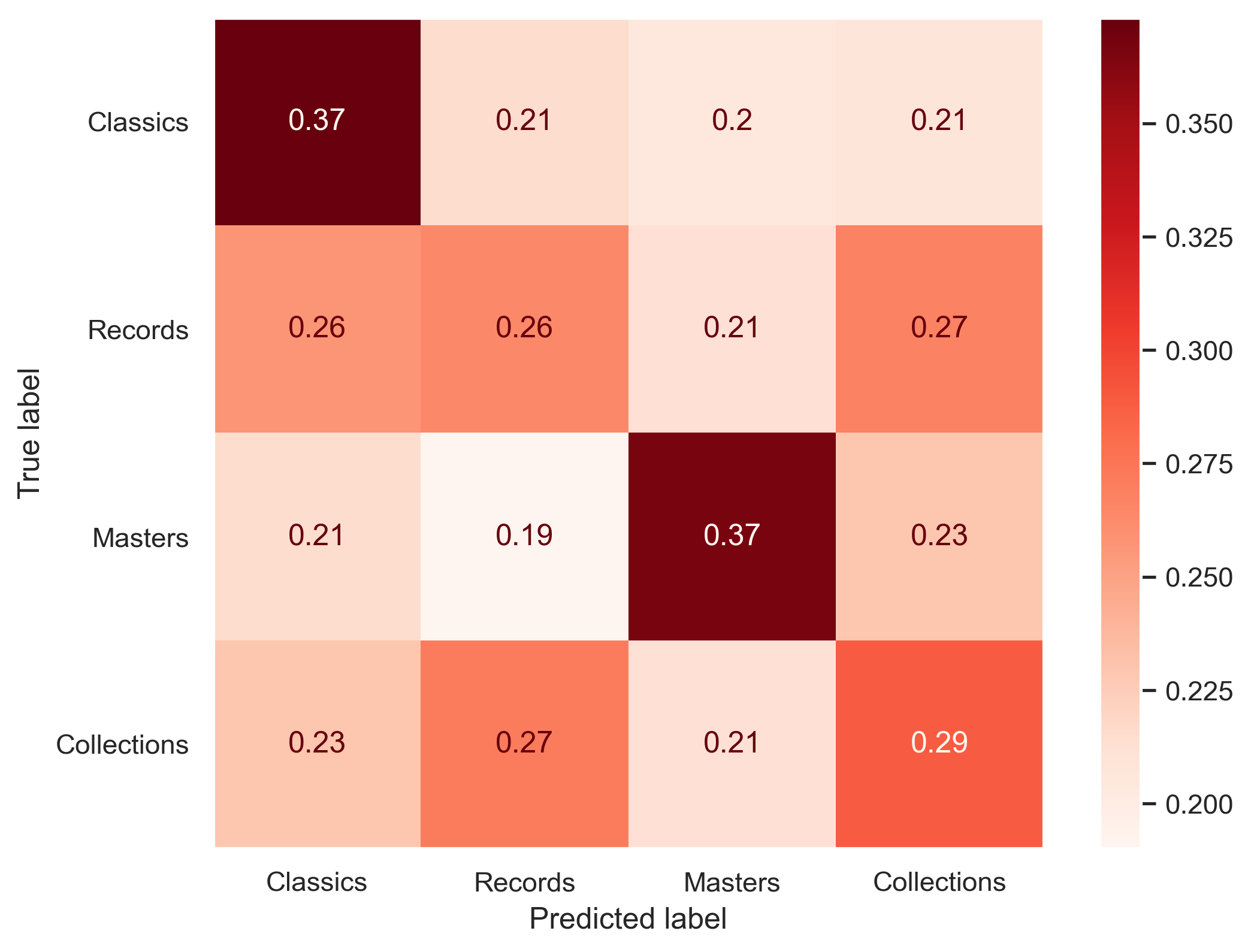

For LCC main class classification, English-language books achieved an accuracy of 0.12 (random classification: 0.05), while Chinese-language books (for LCC main classes with at least 10 instances) achieved an accuracy of 0.26 (random classification: 0.14). For the division classification of the fourfold classification system, Chinese-language books achieved an accuracy of 0.32 (random classification: 0.25). These results indicate that a weak relationship exists between material characteristics and subject categories.

Notably (see Figure 3), despite the classifier’s overall limited performance, the “Classics” and “Masters” divisions stand out with higher accuracies, suggesting that these divisions possess unique material characteristics (higher information density for the “Classics” division, and greater length for the “Masters” division).

Figure 3. Confusion matrix of the division classification of the fourfold classification system

These investigations unveiled subtle but distinct interplays between materiality and content within both 16th–19th century Chinese and English language books. Despite acknowledged challenges in Chinese book metadata stemming from cultural particularities (Shang, Jett, et al. 2023), our results showcased the feasibility of analyzing macroscopic publication trends after meticulous manual corrections. This undertaking addresses global inequities in digital humanities research of book history by diversifying the field in non-Western contexts.