1.

Outline

This paper shows how the semantic modelling of texts can provide a platform for studying complex patterns in the way medieval religious dissidence is narrated in inquisition trial records. The topic connects to the long-running debate over how such documents served to “construct” heresy: our approach, however, provides a more systematic outlook on their content and conditions of production, with greater coverage and, arguably, less preconception. Taking Peter Seila’s register of sentences from the Quercy region of Languedoc (1241–2) as a case study, our investigation builds from the capture of this text as a series of semantic-syntactic data statements via the Computer-Assisted Semantic Text Modelling (CASTEMO) approach (Zbíral et al. 2022). With 649 narrative summaries of guilt thus transformed into structured data, we not only quantify the representation of crimes (taking into account their level of summarization or additional detailing, gender of suspect, sect of dissident interactants, and place and period of sentencing), but also investigate narrative order via sequence analysis methods. In doing so, we shed new light on how religious dissidence was portrayed in inquisition records and the influences upon this: the way an inquisitor questioned, the way suspects responded, and the way notaries summarized.

2.

Background

Medieval records of heresy prosecutions by inquisitors tell stories of religious dissidence concerning thousands of individual suspects that have long fascinated historians. Nevertheless, their mediation by the inquisition process and the effective co-authorship of all its participants (inquisitor and notary as well as suspect) have rendered these narratives the subject of a hotly contested debate over the “construction” of heresy (e.g., Lerner 1972; Biller 2001; Pegg 2001; Biget et al. 2020). The vast majority of treatments, however, focus on the analysis of exceptionally rich narratives, typically drawn from the most detailed defendant deposition records. Much other material, which may appear plainer or even formulaic by comparison (e.g., simpler depositions, summaries of guilt), is simply left aside, even though it too contributes to the narrative portrayal of dissidence within these sources (Zbíral / Shaw 2022: 10–12).

Looking at the totality of narrative content has the potential to uncover previously unseen patterns in the representation of individual crimes (i.e., narrative components) and the way they are woven together in succession (i.e., narrative sequencing). Such patterns may in turn allow us to theorize better the role of the different narrators and the process through which dissidence was actually “constructed” – in the most neutral sense of the term – within inquisition trial records. Even within a single register, however, such an inclusive analysis of the narrative representation of dissidence effectively requires computation, grounded in the extraction of structured data that accurately captures the nuances of narrative. It is to such challenges that this paper turns itself.

3.

Data and Methods

In this paper we take the register derived from the inquisition of the Dominican Peter Seila in Quercy (Languedoc) in 1241–2 (Duvernoy 2001) as a case study for the analysis of narrative components and sequencing in inquisition trial records. Its pertinence is partly founded on it being one of the earliest surviving inquisition registers, as well as on its volume: the register provides summaries of guilt for 649 suspects, typically accused of involvement with the

heretici (ascetic specialists in what later scholarship has often called Catharism) and/or the

valdenses (Waldensian brothers and sisters). Crucially, the summaries – which represent final adjudications of fault, rather than the deposition records on which they were surely based – often appear bland and formulaic. It has even been suggested that they show the trace of a quite restrictive interrogation procedure, similar to that proposed by the interrogatory found in the slightly later

Narbonne Order, an early inquisition manual dated to between 1244 and 1254 (Tardif / Balme 1883; Biller 2022: 364; Taylor 2013: 333). On the other hand, signs of nuance, above all deeper digressions into particular contact occasions, have also been noted (Biller 2022: 364; Taylor 2013: 333–35). A more systematic investigation of narrative patterns thus has the potential to clarify the balance of preconception and exploration within the inquisition process documented by the register.

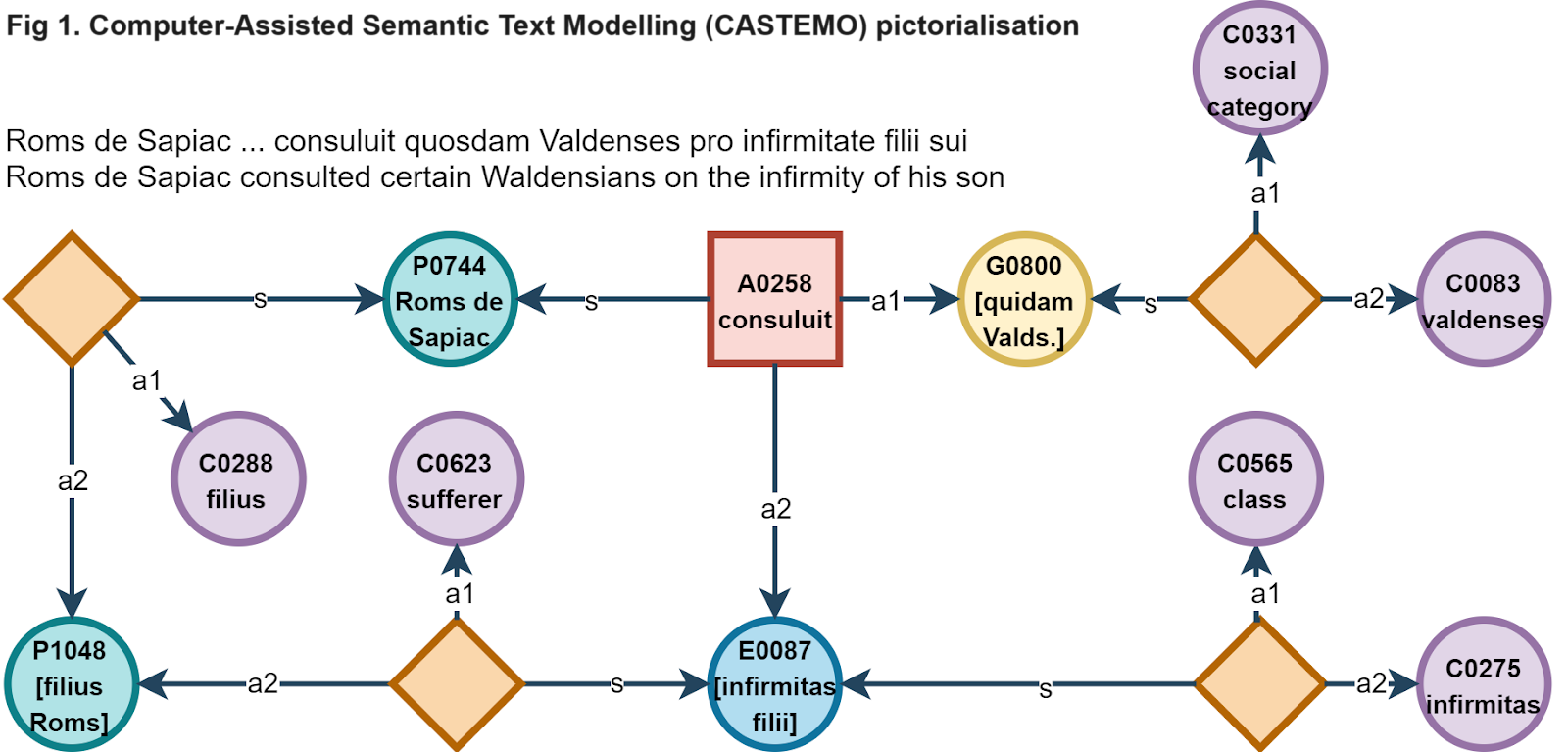

Such an investigation requires the representation of complex narrative features as structured data. Automated approaches to this task have thus far been limited to subject-verb-object extraction (e.g., Andrade and Andersen 2020). Software-assisted but manually-directed approaches to data collection founded on the transformation of textual clauses into analogous semantic-syntactic data statements – of the sort first pioneered within Robert Franzosi’s Quantitative Narrative Analysis (QNA) methodology (Franzosi 2010) and more recently proposed by Computer-Assisted Semantic Text Modelling (CASTEMO) (Zbíral et al. 2022) – offer greater flexibility. For this study, the CASTEMO approach was used to transform the narrative summaries within Peter’s register into c. 10,000 data statements, structured as semantic quadruples (subject, verb, and two object positions). These statements connect "entities” of various types (e.g., Persons, Groups, Concepts, Objects, Locations, Events, and Values) via an Action, with “properties” creating further links between them (see fig. 1). For each crime presented in the register, the exact Latin verbal semantics were captured, as well as all actants, adverbs and adverbial clauses; their position within the text was also preserved. The maximalism enabled by CASTEMO allowed us to avoid any strong pre-categorization of crimes or contexts during data collection: further categorizations were founded on close observations made while encoding the source.

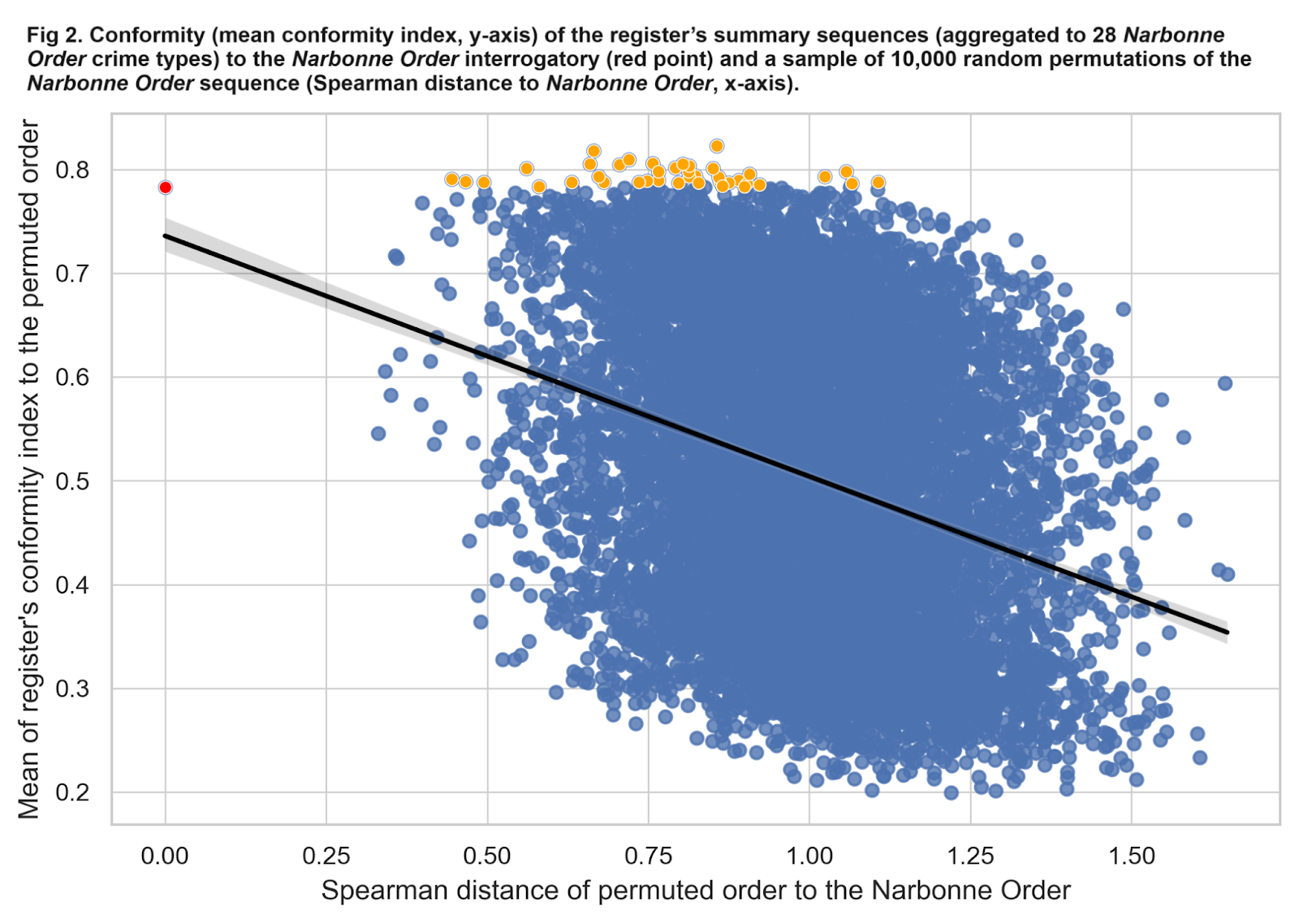

We then created projections enumerating the representation of narrated crimes, their semantic adjuncts (expressing recurrence or additional circumstances) and the trial contexts that frame them (gender of suspect, sect of interactant, place and period of sentencing). The precise preservation of textual sequence in the CASTEMO data also allowed us to explore typical narrative paths and path-dependencies. As part of this, we formally modelled the conformity of each summary crime sequence in Peter’s register to the order of crimes present in the aforementioned

Narbonne Order interrogatory (by way of an index averaging the conformity of each summary crime pair to their order within the interrogatory) and performed a statistical test to assess the strength of this conformity-order relationship against 10,000 randomly permuted re-orderings of the

Narbonne Order interrogatory sequence.

4.

Findings

Our analyses show that the apparent formulaicity of the narrative summaries found in Peter’s register has been overstated. Some crime types receive more detailing, suggesting subtleties of inquisitor-dissident interaction: for instance, expressions of alleviation (such as “but he/she did not know they were heretics”) occur particularly frequently around crimes of eating and drinking with dissident ministers, probably due to the suspicion of ritual contact that hung over such occasions. Variations in crime representation can also be related not only to the sect affiliations of the suspects but also to the location of sentencing events: Peter and his staff were clearly sensitive to variations in what was reported in different places, rather than fitting everyone to a consistent mold. The analysis of narrative sequencing suggests underlying interrogations that explored events in a biographical order, rather than simply crime type-by-crime type (high rate of non-adjacent crime type repetitions), as well as an openness to being led by deponent narration (inconsistency even in sequence-opening crimes). The computed conformity of the order of crimes in the summaries to the

Narbonne Order interrogatory is strong – and stronger than to the vast majority of the 10,000 permuted orders (see fig. 2) – probably representing the influence of similar order features in the underlying depositions. Such similar features, however, appear to have been smaller scale, pertaining to the ordering of very common crime pairs (e.g., “saw” being somewhere before “heard”) rather than overall sequence order: there are thus a number of permuted orders with a relatively high Spearman distance from the

Narbonne Order interrogatory that nevertheless also conform closely with the registers’ summaries. Overall, the results suggest increasingly practiced notarial summarization (later summaries appear more tightly organized by crime type) of depositions that had, in fact, been relatively exploratory. The summaries in Peter’s register thus bear witness to a narrative portrayal of dissidence in Languedoc that was still under construction, rather than pre-constructed and preconceived.