1.

Introduction

The aesthetic transformation of a story into its representation implies choosing a point of view or perspective from which the story is told. The perspective affects how mediated a story is told, often summarized in the juxtaposition of telling versus showing (cf. Lubbock, 1921; Friedman, 1955; Stanzel, 1989). In accordance with different narratological theories, perspective can depend on:

- who is the perceiving and evaluating entity (e.g. Uspenskij, 1975; Rimmon-Kenan, 1983; Schmid, 2014)

- if space and time are centered around a character (e.g. Uspenskij, 1975; Rimmon-Kenan, 1983; Schmid, 2014)

- the relationship of the knowledge of the characters and the narrator (Genette, 2010),

- the extent to which the language is characterized by the narrator or a character (e.g. Uspenskij, 1975; Schmid, 2014).

Therefore, the choice of perspective highly shapes literary interpretation because it influences the reality status of things, for example.

Up to this date, there exists no literary corpus known to the author which is annotated with perspective. Such a corpus would allow for training and evaluation of machine learning models to automatically identify perspective. Existing approaches to this are limited, only differentiating first- and third-person narrative (e.g., Chen & Bunescu, 2021; Eisenberg & Finlayson, 2016). The automatic identification, in turn, would allow investigating a larger number of texts. For example, one could explore if there are genre specific patterns in the development of perspective over the course of a text or examine if biases exist about who the perspective-bearing character is.

To annotate a corpus, the theory that the annotations are based on must be operationalized, i.e., text-based indicators must be found with the help of which the phenomenon can be detected. The process of operationalizing and annotating also enables the evaluation of the theory, as under-defined terms are sharpened, inaccuracies are identified and corrected, and redundancies are uncovered (cf. Pagel et al., 2020, p. 127). This can ultimately lead to a reconceptualization (cf. Weitin et al., 2016, p. 111–113) of the examined phenomenon. Accordingly, this paper presents a first operationalization based on the theory of Schmid (2014) through which the annotation of perspective can be carried out. This partly builds upon Gius (2015) who performed a basic operationalization of the same theory for the analysis of non-fictional speech.

2.

Schmid's Theory on Perspective

Choosing which theory the annotations should be based on involves a series of mostly pragmatic considerations. As the result of the annotation process should be intersubjective, annotation guidelines should have clearly distinguishable categories that are described as detailed as necessary but as generic as possible. It should be clear how the categories relate to each other, what properties they have and how the properties can be identified in a text (cf. Reiter 2020, p. 199). Of the established theories on perspective, the most systematic and text-based one is presented by Schmid (2014). He specifies five parameters which determine the perspective, for three of them subcategories are introduced and for most parameters, textual indicators are described.

According to Schmid (2014, ch. III.2) the conception and the representation of events is determined by the perception, the ideology, the language, the space and the time of the experiencing entity. The narrator can decide whether they choose their own conception (narratorial perspective) or the one of a character (figural perspective) and whether they use their own evaluation and language for the description or the one of a character. The representation of the figural perspective is marked (Schmid, 2014, p. 128), ergo the standard case is that the narrator presents their own perspective (in homodiegetic text this would be the one of the narrating I, not of the experiencing I). Since all indicators given by Schmid refer to the marked figural perspective, the annotation should focus on that.

3.

From Theory to Indicators

Perspective overlaps with the phenomenon of text interference under which the differentiation between a character's text (CT) and the narrator's text (NT) (including speech, thought, perception and values) is understood (Schmid 2014, ch. IV.3). This also influences the degree of mediation of the narrative. Crucially, the same binary distinction as for perspective is employed and the same parameters are used to determine if an interference between the texts takes place (Schmid 2014, p.167-169). All text interference is therefore also an expression of the perspective in place.

Since annotation schemes and taggers for text interference are available (Brunner et al. 2020a; Brunner et al. 2020b)

1

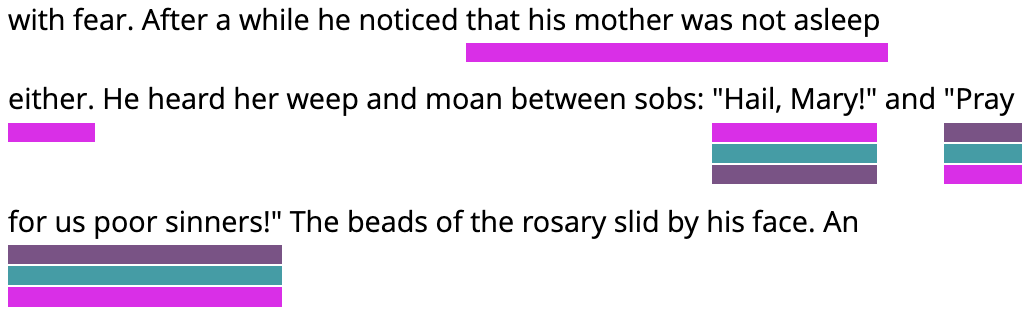

, they can be reused while focusing the operationalization of perspective on what is not covered by Brunner et al.'s guidelines. This includes the representation of a character's perception and emotion which can be treated analogously to the annotation of speech, thought and writing. Furthermore, this includes the spatial and temporal point of view in the CT (marked with deictic adverbs) and any evaluation included in the CT. The previously mentioned parts of perspective and text interference can be understood as strongly marked, an example is shown in Figure 1.

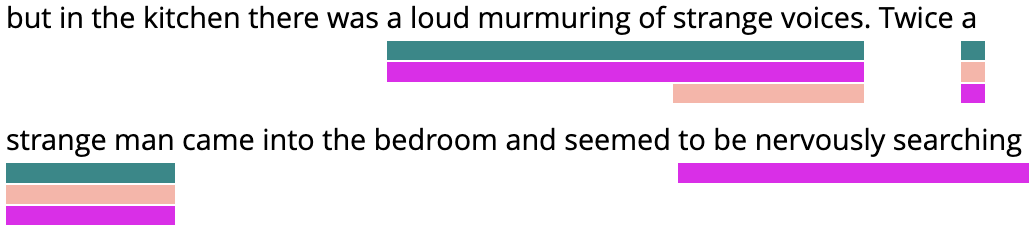

Conversely, Schmid (2022) describes the phenomenon of figurally colored narration (FCN) as an unmarked part of text interference whose identification depends on interpretation (Schmid, 2022, p.4). In FCN, "designations and evaluations" (Schmid, 2022, p.1) of a character "infect" the NT or are "reproduced" in the NT (Schmid, 2022, p. 4). The figural perspective is expressed in terms of linguistics and perception (designation) and ideology (evaluation), for an example see Figure 2. Even though Schmid claims the unmarkedness of the phenomenon, indicators can be found in accordance with the opposition of the NT and the CT since designations and evaluations within the NT can be compared to already identified CT. FCN does not include the spatial and temporal figural perspective, but these can be identified by analysing spatial and temporal deictic adverbs.

To conclude, the annotation of perspective can be divided into the strongly marked representation of speech, thought, writing, emotion and perception of characters, the strongly marked figural representation of time and space in the NT and the weakly marked linguistic, perceptual, and ideological figural perspective in the NT.