A Stylometric Glance at Basque Novels

Objective

This paper proposes a stylometric analysis of 19th-21st century Basque novels to identify unique linguistic characteristics and to create a stylometric map highlighting the trajectory of the genre. It aligns with the conference's focus on reinventing approaches to literature but also addresses the responsibility of preserving linguistic diversity in the digital era.

Historical and Literary Background

The Basque literary canon is a “small literature” created in Euskera, the sole surviving non-Indo-European language in Western Europe (Jansen, 2007). Spoken today in the northernmost part of Spain by a little over 800,000 individuals, the language is a linguistic isolate characterized by high agglutination and suffixation (Rask, 1998).

Euskera did not begin appearing in written form until the 16th century, and it was only in 1881 that Juan Antonio Mogel’s proto-novel, Peru Abarka, was published (Gartzia, 2011). While a cornerstone for Basque fiction, it relied too much on dialogue and lacked sufficient plot to be considered a fully-fledged novel. This status would be awarded eight years later to Domingo Agirre’s Auñemendiko lorea, a Romantic-historical work serialized in the periodical Euskalzale (Olaziregi, 2012). Despite difficult beginnings involving having to skip the stage of realism and jump directly to avant-garde styles, as well as having significantly less time to develop than poetry, the genre made significant strides evidenced by the recognition of Basque novelists with national literary awards (Olaziregi, 2012).

Originally, novels were written in varying dialects of the Basque language. Since the convocation of the Academy of Basque Language in 1968, there have been endeavors at obtaining a more unified, standardized Basque (Olaziregi, 2012). This unification has been instrumental to the growth of the genre despite external pressures and is presently evidenced in the number of annual novel publications. Even the pandemic year of 2020, while seeing a decrease in the overall number of Basque publications, saw an increase in the number of novels from 29 in 2019 to 32 ( Azurmendi, 2021). Various online platforms were further developed to facilitate access to literature in the Basque language.

With many texts available online, the growing body of Basque novels begged closer stylometric investigation. While many of these works have been analyzed before via traditional literary methods involving close reading, to the author´s best knowledge, no stylometric analyses on this corpus exist bar the one that she herself conducted on 57 Basque novels (Weronska, 2024).

Research Quesetions

By embarking on this study, the author wished to explore the Basque literary corpus with new methods answering the questions of how such a “small” literature written in a highly agglutinative language behaves under the stylometric knife. The author wished to create a stylometric map to explore whether works clustered according to author, whether the chronological signal was visible, and how culling and dialectal variation affected the results. The author also wanted to explore differences between translated literature and original Basque novels and whether authors’ sex influenced style in any way.

Method

To this end, I procured over 200 Basque novels from the online platforms of Booktegi, Armiarma , and Susa, converted them to text format, and analyzed them in R using the package Stylo and the functions Cluster Analysis, Bootstrap Consensus Tree, and Oppose . These methods, based on the frequency of the most frequent words (MFWs), have been used successfully in various stylometric studies investigating literary canons (Eder & Rybicki, 2012; Rybicki, 2014; Rybicki, 2017).

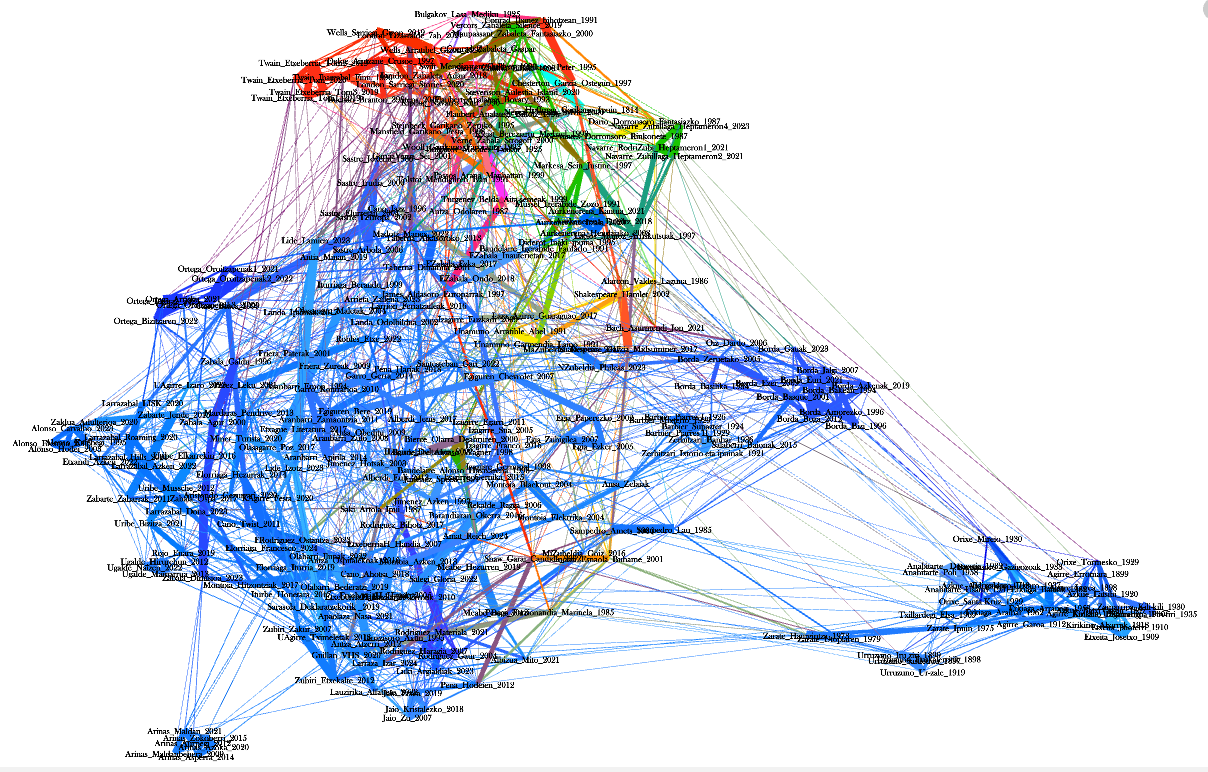

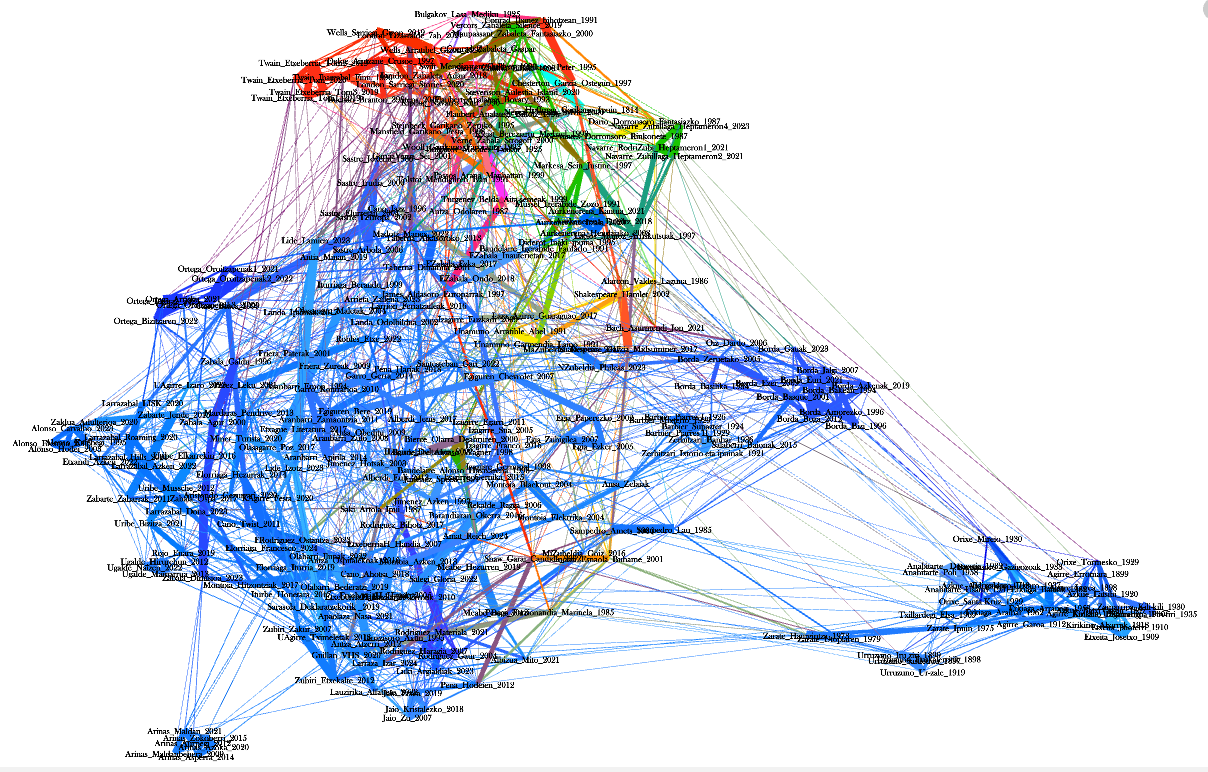

Cluster analysis was performed using 100 MFWs. While this analysis rendered significant accuracy in authorship attribution, the reliability could be improved. To filter out local disturbances, bootstrap consensus tree (BCT) was performed. The attribution test was run several times with different vectors of MFWs (from 100 to 2000) and different settings for culling. The latter was shown to improve authorship attribution reliability. Finally, Basque novels were set against the backdrop of foreign novels translated into Euskara and BCT carried out on this mixed corpus. The results obtained were analyzed using network analysis and visualized on a stylometric map in Gephi (see below).

Results

Some chronological evolution of the Basque novel could be observed. Also, novels originally in Euskara (in blue) remained distinct from translated works (other colors) pointing to the unique linguistic character of the Basque novel.

To explore the stylistic differences between translated and original works as well as between works authored by female and male writers, Oppose was employed. Original Basque novels were shown to put more emphasis on modern, practical vocabulary and local culture. Meanwhile, translated works tended to use more formal, elevated forms and descriptive language. Female writing tended to be more reflective and formal. It tended to use more negation and archaic forms with an emphasis on relationships and sensory-emotional experience. Male authors, on the other hand, seemed to prefer action and directness. They used more familiar, emphatic forms and affirmatives.

To conclude, stylometric methods were found to be mostly successful in the authorship attribution of works forming a “small” literature and written in a highly inflected language. Culling was found to increase the reliability of authorship attribution when dealing with works in different dialects. Novels penned in Euskera before 2000 remained mostly distinct from translated works pointing to a unique character of the early Basque novel. Translations were found to contain instances of translationese . Finally, variation between novels penned by female and male authors was observed on a linguistic level.